Today I have the honor of interviewing author, editor, and podcaster, Scott Edelman. He recently interviewed me on his unique podcast, Eating the Fantastic and we’re delighted he could visit our modest skyscraper at Poseidon’s Scribe Enterprises for an interview.

Scott Edelman has published over 100 short stories in magazines such as Analog, The Twilight Zone, Postscripts, Absolute Magnitude, Science Fiction Review and Fantasy Book, and in anthologies such as You, Human, The Solaris Book of New Science Fiction, Crossroads, MetaHorror, Once Upon a Galaxy, Moon Shots, Mars Probes, and Forbidden Planets. His poetry has appeared in Asimov’s, Amazing, Dreams and Nightmares, and others.

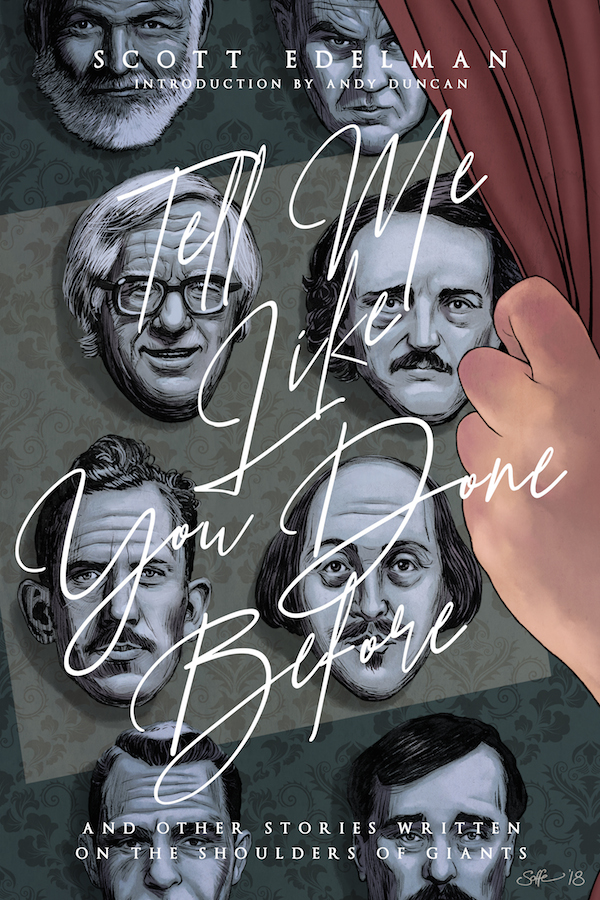

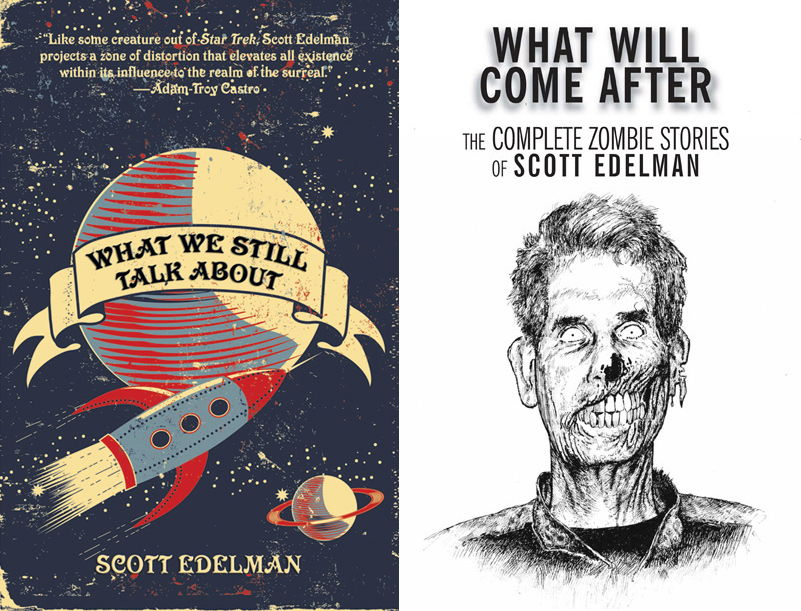

His recent short story collection is Things That Never Happened. Of that book, Publishers Weekly wrote: “His talent is undeniable.” Other collections include Tell Me What You Done Before (and Other Stories Written on the Shoulders of Giants), What Will Come After, and What We Still Talk About. He has been a Stoker Award finalist eight times, and What Will Come After was a finalist for the Shirley Jackson Award.

Additionally, Edelman worked as an editor for the Syfy Channel. Magazines he edited include Science Fiction Age, Sci-Fi Universe, Sci-Fi Flix, Satellite Orbit, and Rampage. He has been a four-time Hugo Award finalist for Best Editor.

He got his start editing at Marvel Comics, writing ad copy and editing the Marvel-produced fan magazine FOOM (Friend of Ol’ Marvel). He also wrote trade paperbacks such as The Captain Midnight Action Book of Sports, Health and Nutrition and The Mighty Marvel Fun Book number four and five. After leaving Marvel, he freelanced for both Marvel and DC, and his scripts appeared in Captain Marvel, Master of Kung Fu, Omega the Unknown, Time Warp, House of Mystery, Weird War Tales, Welcome Back, Kotter and others.

His first novel, The Gift, was a finalist for a Lambda Literary Award in the category of Best Gay SF/Fantasy Novel. His writing for television includes Saturday morning cartoon work for Hanna Barbera and treatments for the syndicated TV show Tales from the Darkside (the episodes “Fear of Floating,” “Baker’s Dozen” and “My Ghost Writer, the Vampire”). His book reviews have appeared in The Washington Post, The New York Review of Science Fiction, and Science Fiction and Fantasy Book Review.

An awesome bio! Here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Scott Edelman: The earliest writing I can remember doing—back when I was only in the single digits, probably around the 3rd Grade—were prose stories of comic book characters who hadn’t yet met in the pages of the comics themselves, but who I very much wished would get together. I scribbled out long, complicated encounters between all the Marvel and DC characters—something which wouldn’t happen in the real life world for several decades. So it was a case of writing the stories I wish had already been written by others, but since they hadn’t yet done it, I had to do it myself. And once I’d done that, I learned I enjoyed telling stories.

But the first story I ever wrote and submitted professionally came about after I’d read a few of Robert E. Howard’s Conan stories, and with the ego of youth, thought, “Hey, I can do that!” So at age 16, I wrote what would be my first story every written with the goal of publication. It was about a barbarian warrior on a quest, was sent off to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, from which it was rejected in three days.

And several thousand rejections (I stopped counting after my first 1,000) and 113 short story sales later, here I still am.

P.S.: I’m sure people are fascinated that you worked at Marvel Comics. Please describe what that was like, and your advice for writers thinking of working in comics today.

S.E.: I have no useful advice whatsoever for writers thinking of working in comics today. I wouldn’t even have had advice for writers who hoped to work in comics at the same time I did, which was in 1974, 48 years ago. That’s because it all happened by accident! Serendipity has always been my friend.

I’d never intended to work in comics. I’d always thought I’d be a journalist, and hopefully become a three-day-a-week newspaper columnist in the Pete Hamill or Jimmy Breslin vein, names which probably mean little to contemporary readers. I was a comics fan who, living in Brooklyn as I did, was able to become friends with the professional writers, editors, and artists who worked at Marvel and DC through the convention circuit, but I wanted nothing from them. I wasn’t on the make for freelance assignments or a staff job. But then one came looking for me.

A comics fan named Duffy Vohland who’d moved to New York to begin working for Marvel rented an apartment in my neighborhood, and as he was unloading his possessions, some local kids saw his boxes of comics, and told him there was another guy only a few blocks away who also collected comics—me. So one day, he showed up at my door, we became friends, one thing led to another, and when a job opening happened at Marvel Comics, I was asked to apply.

So I got my job because a) I was born in Brooklyn b) started attending comic book conventions when they were small c) developed friendships with creators d) had someone move into my neighborhood e) was offered a job…and several other steps which no one could possibly replicate. How to do it today? No idea!

As for what it was like…it was a job which didn’t feel like a job, and from which none of us ever wanted to go home. Imagine the Dick Van Dyke Show, except about comics. No one ever wanted to leave, because we were living in a dream, and didn’t want to wake up. In the evenings we’d go to restaurants and movies together, or play poker, and on the weekends, we’d get together for volleyball and BBQ. There was no separation between work and the wider community of comics professionals of the ‘70s. It was the most creative group of people I’ve ever worked with. It was a family.

And eventually it became more than a family, because that’s where I found my wife, with whom this year I’ll celebrate my 46th anniversary.

P.S.: In what ways, if any, did your start in the comic book industry shape your later fiction writing?

S.E.: What I took away from my time in comics were lessons about what I didn’t want my prose fiction career to be like.

To begin with, it had multiple negative effects. First, I found it difficult to write what I wanted to write, vs. what others wanted me to write. It’s hard to turn down writing assignments when you know whatever you hand in on a Friday you’ll be paid for the following Wednesday. So I was writing not just comics, but letter columns, house ads, etc., doing those rather than my own writing. I shut down my muse during those years. I was the embodiment of what George Bernard Shaw meant when he wrote: “If you want to be a writer, you must have money, otherwise people will throw money at your head to buy your talent to use it and distort it for their own frivolous purpose.” A dreadful warning!

But in addition to stealing my time, comics also affected my style. I noticed the writing I did manage to find time to write for myself began to sound more and more like Stan Lee’s Bullpen Bulletins prose. Bombastic. Alliterative. His style had seeped into my subconscious and I was unable to control my word choices.

But remember—I was only age 19 when I started in comics, not yet mature enough to keep the walls separated between the writing I did for myself and the writing I did for others. Later on, during my years editing Science Fiction Age and working for the Syfy Channel, I was able to maintain that separation, But back then, I knew the only way I’d get back to my own fiction again, written my own way, was to leave. And so began a series of non-creative jobs so I could protect what I considered the most important.

That’s not to say I didn’t love my time there. But I probably loved comics too much for my own good, and would probably have been better off remaining a fan than becoming part of the industry.

P.S.: Who are the three main people who influenced your writing? What are three of your favorite books?

S.E.: My answer would differ depending on when you asked me that question. When I was a kid, I’d say Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, and Arthur C. Clarke. As a teen, my triumvirate was instead Harlan Ellison, Samuel R. Delany, and Roger Zelazny. Next came Italo Calvino, Raymond Carver, and James Tiptree, Jr. (that is, Alice Sheldon).

But influence doesn’t end just because we’re no longer at the beginning. I continue to be influenced by my peers. So I take from writers such as (to name just a few) Sarah Pinsker, P. Djèlí Clark, Meg Elison, Fonda Lee, Andy Duncan, Sam J. Miller, Amal El-Mohtar, Victor LaValle, Alyssa Wong, Sam J. Miller…I could go on. They are as much an inspiration as any of those I encountered when I was starting. It’s important to continue to read widely, and to leave ourselves open to the future as well as the past.

As for my favorite books, I’d prefer to share three short stories I return to and reread year after year, because they still amaze me—

“Day Million,” by Frederick Pohl

“What We Talk About When We Talk About Love,” by Raymond Carver

“The Women Men Don’t See” by James Tiptree, Jr.

P.S.: You’ve written for, and in, so many mediums—short stories, novels, poems, comic books, television, podcasting, etc.—which is your favorite, and why?

S.E.: It will now and forever be the short story. I am a minimalist, and my sweet spot when writing is 5,000-7,000 words. I prefer to create stories which can be consumed in a single sitting, so the whole of it can be contained in one’s head at once. I feel no need to fill in the entire background history of a character, or what happens next once the story is over, or to follow every untold side tangent which might arise. The only novel I’ve ever published was originally a short story, but it got away from me in rewrites, and I find the chances of that repeating as highly unlikely. I’ve heard it said that a short story is the most important moment in a person’s life, after which they are changed forever, or conversely, decide they’ll never change. Those are the moments I always wish to explore.

P.S.: Is there a common attribute that ties your fiction together (genre, character types, settings, themes) or are you a more eclectic author?

S.E.: If you look past genre, the common attribute is love. Theodore Sturgeon once said all of his stories were actually love stories, and I think anyone who reads widely in my published fiction—and I just placed my 113th story last week—will see that as my most predominant theme, though there are others.

But in terms of form and genre, I am indeed eclectic. The opening line of my entry in the Science Fiction Encyclopedia reads: “US editor and author, his fiction having had perhaps unduly little recognition, almost certainly because his work shifts from horror to fantasy to SF without any marketing consistency.” I wear that description as a badge of honor! I will always use any metaphorical tools to tell the stories I want to tell.

P.S.: Much of your writing leans to the horror side. What fascinates you about that genre?

S.E.: Your question made me curious about the true extent of my relationship with horror, so I ran down my list of 113 published (and about to be published) stories and discovered the breakdown is—

- 43% horror

- 34 % science fiction

- 20% fantasy

- 3% metafictional/unclassifiable

Which I thought intriguing…but unsurprising.

But those percentages shift if I categorize only the most recent 25 stories, though—

- 48% science fiction

- 30% fantasy

- 22% horror

So over the past five years, I was still writing horror… just not as high a percentage of my output as before. The only explanation I can imagine for that shift is—the horror of the 2016 election and what came after was enough for me, and for that period of time, I didn’t feel felt like dwelling there. But I imagine that shift is only temporary.

As for why I love horror…it provides me with an amazing toolbox of metaphors with which to speak of our true fears—the fear of aging, the fear of loneliness, the fear of loss of agency, the fear of loss of self. Wrapping those fears in zombies, ghosts, vampires and the less traditional horrors makes them more terrifying…and more poignant.

Though sometimes, of course, it isn’t about the metaphors, and zombies are just cool!

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

S.E.: The most difficult aspect of writing for me is my writing method itself, as I have learned my best work only comes when I scribble my first drafts longhand, and then edit them the same way. I’ve tried to compose at a keyboard, but when I do, either nothing comes, or if it does, its either clumsy or facile. So I write with pen and paper, then key it into a computer, and print it out to do edits and revisions…which I then key in, print out, and do the same over and over again.

And another thing that’s difficult for me, I guess—though I don’t think of it as difficult, just slow—is that I can’t begin a day’s writing without rereading all words on a particular work up to that point. So if I left off in the middle of page 10, I must the next day slowly reread all that went before, rebuilding the house of cards in my head. And if it’s a novella, I must reread dozens of pages. I can never jump right in.

As for the easiest? I will never run out of ideas! I usually get 3-4 new ones for each one I write, so I will never catch up during this or any other lifetime. I am grateful for my subconscious, which collaborates with me that way.

P.S.: I was pleased to participate in your unique podcast, “Eating the Fantastic.” Tell us about that podcast series—how it started and what listeners can learn from it.

S.E.: I’d been a guest on many podcasts in my life, but it wasn’t until I appeared on The Horror Show with Brian Keene podcast during its first year that I thought—hey, I can do that! I love talking to people, love finding out their secret origins and how they do what they do. But I knew there were dozens, if not hundreds, of interview shows out there. How to differentiate mine from all the others? What would be my niche? I decided to marry my love of food and love of people into a single podcast—but one which was about the people more than the food.

My love of tracking down good food while traveling the world attending conventions was so well known one blogger dubbed me “science fiction’s Anthony Bourdain.” And since the con away from the con—which takes place when I wander off-site with friends for a meal—can often be more fun than the con itself, I decided to replicate that good conversation with good friends over good food for listeners.

I believe food relaxes my guests, loosens their tongues, distracts them from the interview process so they sometimes forget they’re even recording, and as a result, gives listeners a more intimate picture of them than any studio podcast where the guests is always aware they’re “on.”

As for what listeners can learn from it—across the nearly 300 hours so far, they’ll hear from nearly 250 writers, editors, and agents about both the art and craft of writing. They’ll feel they’re at the table with us, learning as I learn how they create the fiction of the fantastic we love.

P.S.: Tell us about Things That Never Happened. How did that book, and its interesting cover, happen?

S.E.: I wish there was some fascinating backstory I could tell you about why and how my most recent collection came to exist, but it’s merely that I had reached critical mass of a certain type of story—dark fantasies of the Twilight Zone-ish type—and so began looking for publisher willing to join me on the project. That’s often the way collections occur for me—when looking back at the mass of stories in my wake—currently 113 of them—and seeing such similarities. Luckily, Norm Prentiss of Cemetery Dance was willing to take me on, and I’m extremely pleased with the result.

As for the cover of Things That Never Happened, I’m so glad I had nothing to do with the creation other than to inspire artist Lynne Hansen with my stories. The covers I’d helped design myself have all been disasters. Which is an important lesson to learn—just because you’re a writer, it doesn’t mean you’re also a cover designer who can help create what’s essentially an advertisement for you book. The ones I had anything to do with I later realized repelled rather than attracted readers. Those mistakes were how I learned to stay out of cover design other than to say “thank you very much” when others do great work.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

S.E.: I dislike talking about my stories in progress—not just until after I’ve finishing writing them—but also not until they’re sold and published. But I will say this much—

I earlier today completed the first draft of a new fantasy story which came in at around 4,200 words—and for which the ending I decided necessary is, I fear, almost impossible to pull off. But I’ve always felt that if I’m not always attempting to do something I think can’t be done, what’s the point?

Some believe a writer—or anyone in any field—should stick to their strengths. But I’ve always felt I should stick to my weaknesses. How else will I get better, and level up to the point where one of my facets becomes a strength rather than a weakness? Writing, like anything else, is a muscle, and I can only get better by doing what is hard, what needs improvement.

I’m able to do this, I think, because I recognize my writing life is more about a career than any particular story, which means what attempting to get something right this time around might do, even if I should fail, is equip me for getting it right next time. At least that’s what I hope.

And that’s all I feel comfortable saying about my current story—which still has about 10 working titles. My next step, before diving into draft two, will be to winnow down to the final one, because that will focus me as I move on.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer to aspiring writers?

Scott Edelman: I think I’ve already given some with my previous answer, but the most important advice I can give is to repeat the memorable line from Galaxy Quest: “Never give up! Never surrender!”

The reason I’m still here isn’t because I was any good when I began. It’s because in the face of rejection—the first of which I received at age 16, remember—I never took it personally. I kept writing, I kept submitting—and because inevitably, if one does both of those things—I kept improving.

If you can find find joy in your work, so that the writing can be its own reward, if you can focus on having fun writing the next story rather than worrying about the fate of the last one, you will eventually achieve your goals.

I urge you to find joy in telling the tales you want to tell, the ones only you can tell. I can think of no better life than that.

Thank you very much, Scott. Readers of my blog can find out much more about Scott at his website, or on Twitter, Instagram, or Facebook . Also check out his podcast.

Poseidon’s Scribe