When I read the title of Stephanie Lee’s article in The New York Times, “Why ‘Find Your Passion’ is Such Terrible Advice,” I gaped in astonishment. Was she saying ‘Don’t Find Your Passion; Live a Passion-Free Life’? What kind of life is that?

Then I read her article, and I encourage you to do so as well. She’s really saying you should have the right attitude as you seek your life’s passion. Though she doesn’t provide alternative advice, I believe she would have you ‘find and develop your passion.’

The shorter version (“Find your passion”) may lead someone to believe it’s just about the search. “Ah, I’ve found something I enjoy. Now the gods will smile on me and I’ll simply display my in-born talent for the world to see.”

Lee’s article drew heavily from a study by P.A. O’Keefe, C.S. Dweck, and G.M. Walton called “Implicit Theories of Interest: Finding Your Passion or Developing It?” The study contrasted people with two views:

- Fixed Mindset. These people are uninterested in things beyond their accustomed interests. When they do try new things, they don’t foresee difficulties and lose interest quickly when they encounter problems.

- Growth Mindset. People with this viewpoint assume they must develop their passions over time. They know they’ll have to invest effort and overcome obstacles.

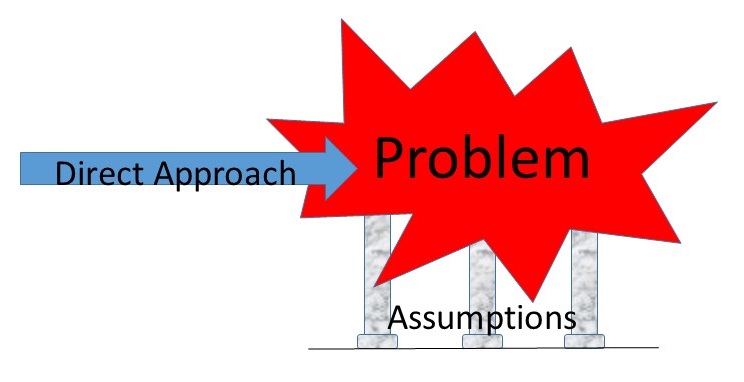

The study’s authors worried that if you tell someone with a fixed mindset to “find your passion,” that person will likely pour energy into a single interest and quit when the going gets tough. Moreover, the person may generalize that failure and conclude she or he won’t be good at anything.

Those with a fixed mindset are limiting themselves and missing an opportunity to enjoy some interest in life. The key, then, is to shake off the fixed mindset and adopt a growth mindset. But how?

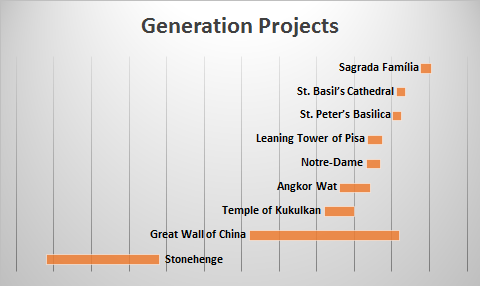

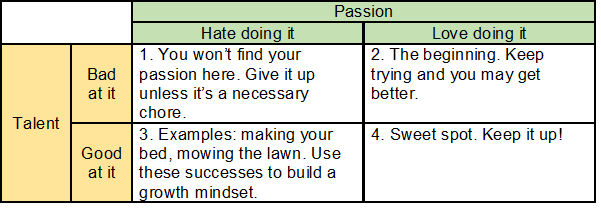

First, I’d like to separate two things people often mix up. Let’s define passion as a strong interest in, even love of, some activity. Let’s define talent as a level of skill in performing some activity. This sets up the four possibilities illustrated in this table.

The key quadrants are 2 and 3. Quadrant 3 points the way out of the fixed mindset. By enjoying and celebrating the fruits of small achievements, you begin to associate favorable outcomes with effort and determination. Quadrant 2 is where all passions start. With any luck, your enjoyment of the activity will carry you through the inevitable difficulties and setbacks.

How does this apply to writing fiction? Like any other activity, some love doing it and some hate it. Some are skilled enough to produce good stories and others lack that talent. I suspect there are very few in Quadrant 3, who hate writing but somehow produce high-quality stories.

If you’re in Quadrant 2 and struggling to get to Quadrant 4, you’ll need that growth mindset to keep you plugging away, writing better stories and perfecting your craft.

If you suffer from the fixed mindset, think about the Quadrant 3 areas of your life. You do have a talent for some things, after all. You didn’t become good at them by accident. You worked at them and persevered. Now do the same thing by writing some fiction.

In summary, find and develop your passion for writing fiction. That’s the non-terrible advice of—

Poseidon’s Scribe