Are milieu and ambiance important, perhaps even necessary, for the act of writing?

Milieu means surroundings, environment. Ambiance means the mood created by an environment. As a writer, you strive for a creative, productive mood, particularly one that results in a string of words soon to become a best-seller. Before sitting down to write, do you arrange a milieu conducive to achieving that ambiance? Let’s examine the aspects involved.

Sight

You don’t gaze at the screen or page all the time. Now and then you glance up. When you do, what visual surroundings do you prefer to see? Do you lean toward a natural view—vistas of the outside world including trees, flowers, mountains, lakes, etc.? Or are you the decorative indoor type—furnishing your writing space with paintings, knick-knacks, posters, figurines, or other delights for the eye? Perhaps visual clutter distracts you, and you seek a bare, spartan environment. Or do your visual surroundings matter at all?

Sound

Does noise, or its absence, harmonize with your writing? Some writers hate sound of any kind. Even the ticking of a clock or the hum of a fan disturbs them. Others prefer the quiet murmurs of nature—twittering birds and babbling creeks. Others put on recorded music, a background soundtrack of their writing passion. Perhaps, for them, certain songs match the rhythm of their creativity. Other writers tap into music more in tune with the specific mood or setting of their work-in-progress.

Smell

Scientists claim a strong link exists between odor and mood. Do you follow your nose to improved creativity or prolificness, or both? Do you achieve your optimum olfactory atmosphere via flowers, perfume, potpourri, or incense? Perhaps you turn your nose up at fragrances altogether, not caring one whiff about them.

Touch

Does the tactile sense reach out and poke your creative nerves? Does it help to stroke the fur of a pet or stuffed animal? Is the comfiness of your chair a factor? Maybe the feel of a pen in your hand rubs you the right way.

Taste

Bundled with smell, taste hits the spot for some writers. We’ve all heard accounts of authors who required alcohol to write, but I’m not sure I swallow that. In fact, I’d caution against forming a strong association between writing and tastes. Once that mental link gets established, you’ll strive to write better by eating or drinking more. Too much food or drink can harm your health.

Locale

For the above sensory factors, locale plays a role. Do you write outdoors, preferring a natural setting, disdaining the artificial? Or is the indoor milieu more your style, a place you can shape and adjust as you please, without the bother of insects?

Mental State

We’ve been assuming a process of ambiance—allowing the milieu to create a mood. Perhaps, however, you attain your optimum mental state in a more direct, way. Maybe you reach your creative mood through meditation. Or, more simply, you read and think about what you’ve written before to put yourself in the right frame of mind to continue on. In other words (with apologies to Decartes), you think, therefore you can write.

Experimentation

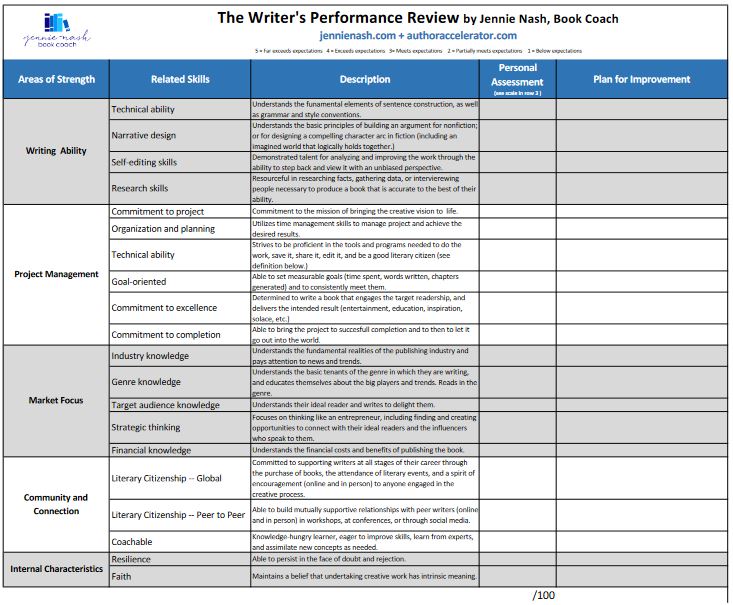

Maybe you haven’t a clue about the answers to any questions I’ve asked, but you’d like to find out. No problem. Do what a scientist would do—experiment. Try out different milieu and assess the resulting ambiance. Compare the way you write in these different environments. You’re not looking for surroundings that you find most pleasurable, but the one that results in your best prose. Readers, of course, may differ from your assessment and then you’ll face an interesting choice—go with what you prefer, or with what your audience wants.

As for me…

Throughout this post, I’ve proposed things for you to consider as you write. You might be interested in my choice of milieu and its ensuing ambiance. Why you’d be interested in that is a question only you can answer.

I favor the make-your-own-mental-state approach without regard to any milieu. I like to think I can write anywhere. However, if I should, one day, discover just the right environment to generate a best-seller, that would lock in that particular milieu and ambiance for—

Poseidon’s Scribe