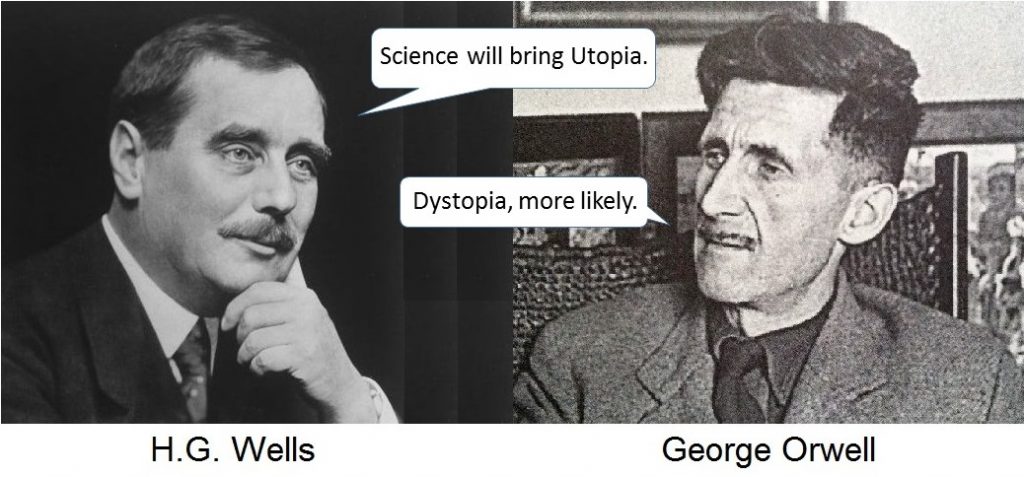

Will Science save humankind, or lead us to our doom? The Internet is buzzing lately with various online outlets reprinting this article by Richard Gunderman in The Conversation, about a debate between H. G. Wells and George Orwell on this topic.

H.G. Wells, best known for his science fiction novels such as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, believed science was the best hope for humanity’s future. George Orwell, an essayist, critic, and author of 1984 and Animal Farm, took a less optimistic view.

H.G. Wells, best known for his science fiction novels such as The War of the Worlds and The Time Machine, believed science was the best hope for humanity’s future. George Orwell, an essayist, critic, and author of 1984 and Animal Farm, took a less optimistic view.

The article makes it sound like a lively back-and-forth argument ensued, but from the essays cited, it seems rather one-sided. In the early 1940s, H.G. Wells was in his late 70s and near death. George Orwell was in his late 30s, (though not too far from his own death at 46). From what I can glean, this was mostly Orwell criticizing Wells, not the other way around.

Before we explore the ‘debate,’ let me define terms. Science is a systematic process for gaining knowledge about the universe through experimentation. Since it involves the accumulation of knowledge, it’s unlikely that Science, by itself, can either save or destroy humanity. I think of Engineering as the application of scientific knowledge to design, invent, and produce useful products.

When both Wells and Orwell refer to Science, I think they meant to include Engineering. For the purpose of this blogpost, I’ll use that same shorthand meaning of Science.

Wells grew up in an era far different from Orwell’s. He saw the rapid development of science—automobiles, submarines, airplanes, relativity, skyscrapers, rocketry, and medicine—and foresaw amazing wonders that would benefit mankind. He figured the same scientific process that could produce those wonders could also lead to better government if we placed scientists in charge.

Let’s give Wells some credit, though. He was no Pollyanna. Many of his novels portrayed the misuse of science for destructive ends. But George Orwell seized on some of Wells’ more optimistic—though lesser known—writings.

In the early 1940s, Orwell watched with growing horror at the growth of Hitler’s Germany and saw it as the embodiment of Wells’ ideas, a nation of submarines, rockets, and airplanes, with science-minded people running the show. To Orwell, Deutschland was no Utopia. He castigated Wells in a couple of scathing essays.

In his article in The Conversation, Gunderman claims the debate is still relevant today. It’s been 75 years since Orwell penned his criticisms; have we learned enough to settle the argument?

Since that time, Science has split the atom to provide electricity, visited the Marianas Trench, landed on the Moon, built and commercialized the Internet, put instant communication in our pockets, sent probes to explore the outer planets, multiplied crop yields, mapped the human genome, and extended lifespans through medical breakthroughs.

On the other hand, Science also brought us nuclear weapons, the Apollo 1 fire and two space shuttle disasters, Chernobyl, computer viruses, armed drones, and electronic spying. Soon, perhaps, an artificial intelligence Singularity may be looming.

In my view, science is a tool, like a knife or hammer. People can use it for good or evil. It amplifies our capacity for both. The concepts of good or evil reside in the individual human mind. To ask if Science will save humanity is like asking if a hammer will save humanity. It depends on how we use the tool.

The real question is whether our good natures will prevail over our evil ones. I think there are far more good people than evil ones, but the evil ones have greater influence per capita. For some reason, a few clever evil people can sway many good people to their side.

So far, across the span of human time our good natures have won out and the products of science have proffered more benefits than harm. On average, life is better now than in the past, for most. But it’s a close thing, and our history shows frequent backsliding.

Whether humanity achieves Utopia, destroys itself, or some outcome in between, Science will deserve neither credit nor blame. Only the human capacity for love or hate will determine our future. And that’s the realm of fiction writers like—

Poseidon’s Scribe

We live in a distraction-rich environment. Even before the Internet, there were rooms to clean, library books to return, lawns to mow, desk items to straighten, and windows to gaze through. Today, there are Facebook posts to like, tweets to retweet, texts to answer, online stores to shop in, blog posts to read, and new sites to explore.

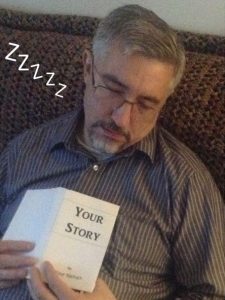

We live in a distraction-rich environment. Even before the Internet, there were rooms to clean, library books to return, lawns to mow, desk items to straighten, and windows to gaze through. Today, there are Facebook posts to like, tweets to retweet, texts to answer, online stores to shop in, blog posts to read, and new sites to explore. Let’s say you’re looking over the story you just finished writing and you see a section where the action really drags. While writing, it seemed necessary to describe a scene fully or explain a character’s backstory so later plot actions would make sense. Now you’re torn. Should you follow Hitchcock’s advice and just cut that section, or leave it in at the risk of boring your readers?

Let’s say you’re looking over the story you just finished writing and you see a section where the action really drags. While writing, it seemed necessary to describe a scene fully or explain a character’s backstory so later plot actions would make sense. Now you’re torn. Should you follow Hitchcock’s advice and just cut that section, or leave it in at the risk of boring your readers?