As a writer, you’re trying to form a daily routine of writing well. Or is that a good habit of writing well? Or a ritual? Let’s clear this up.

According to neuroscience expert Anne-Laure Le Cunff of Ness Labs, all three are periodically repeating actions, but there are differences. I’m going to put my own spin on the ideas Ms. Le Cunff presented in her article.

Routine. This type of action is conscious and deliberate. A routine requires thought and willpower to do. If a strong intent isn’t there each time, you’ll just stop doing the routine, or you’ll delay it until the last minute.

Examples of routines include exercising, cleaning your room, and paying taxes.

Habit. This is an action prompted by an automatic urge, usually triggered by some cue. The closer your mind connects the action to the cue, the more fixed the habit becomes. Habits can be good or bad, and human nature makes it easy to slip into bad ones and easy to slip out of good ones.

Examples of habits include getting up with an alarm clock, brushing teeth after eating, and checking email first after turning on your computer.

Ritual. An action intended to better yourself, not just maintain your existence. It gives you purpose and fulfillment. Your focus is on enjoying the task, not just getting through it.

Examples of rituals include meditation, learning a new language, and practicing a musical instrument.

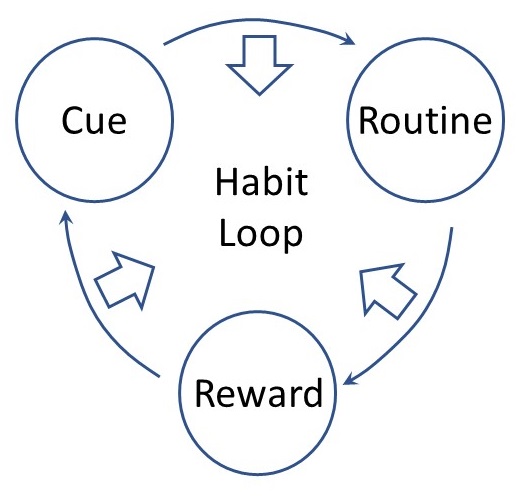

If you intend to be a good writer, which of the three are you aiming for? To answer that, you need to understand one more concept first—the Habit Loop.

I believe all habits start off as routines. For example, the first time you brushed your teeth, you had to think through the process. It was a routine, requiring intent and concentration. Later, after it became a habit, you performed it automatically, usually right after eating.

How do routines become habits? By using the Habit Loop.

The idea here is to use a cue of some kind to trigger the task, and then reward yourself for completing it. By shortening the time of the cycle, particularly the cue-routine gap and the routine-reward gap, you help ingrain the routine as a habit. That’s what the inward-pointing arrows signify.

How does all this apply to writing? For simplicity, let’s separate writing into three tasks:

- Initiation—sitting down to write. I recommend making this a daily habit. Use the Habit Loop to ingrain it, if necessary. For beginning writers, Initiation is the most important task. After all, the other two can’t take place if you don’t plunk yourself down in the chair to write first.

- Conceptualization—choosing a genre, constructing a plot, fleshing out characters. I think of this as a ritual, in the sense of being done for the sheer joy of writing. This requires considerable conscious thought and creativity, and should not be considered a chore. Don’t get into a habit rut by writing stories with the same theme, similar characters, common settings, etc. Keep things fresh.

- Mechanics—stringing sentences together, choosing words, etc. Some days, this may seem like a ritual, an enjoyable task done for its own sake. Other days, it may seem like a routine, a task requiring thought but one you look forward to completing. Perhaps for truly experienced authors, this becomes more automatic, like a habit.

Is writing a routine, habit, or ritual? Apparently, it is all three. It’s a routine/habit/ritual much loved by—

Poseidon’s Scribe