Real-life humans (you and me, for example) eat food to convert it to energy and use that to grow and move. Fictional characters get along just fine without food. Why, then, do we often read entire scenes showing characters eating?

On the other hand, many novels and short stories don’t mention food at all. Fictional years and decades may pass without a character consuming even one morsel or drinking one drop. Yet the character doesn’t die of starvation. What’s with that?

Readers assume a character eats ‘off-stage,’ just as we assume characters use the bathroom as needed without the author belaboring the waste expulsion process.

Since readers will assume a character eats, that takes us back to our original question—why do authors sometimes describe a character eating? I’ve come up with a dozen reasons, though there may be more:

- Setting. Food represents part of the setting in which the characters speak and interact. An author’s description of food helps the reader picture the location and background. Depending on the author’s intent, the food may complement the rest of the setting or provide a counterpoint to it.

- Authenticity. Some stories feature food as a central part of the story, and the author must show the character eating for the sake of realism. It would seem weird if the character didn’t eat.

- Mood. The author can use food to show mood. (Apparently that’s true for poets, too.) A character’s opinion about food clues the reader into the character’s state of mind. That mood might not match the character’s out-loud dialogue, but will reveal the character’s true emotions.

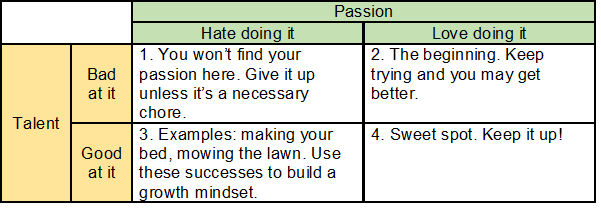

- Talent. The preparation of food, especially difficult or dangerous types of prep, can showcase a character’s talent. Even an odd method of eating food (such as tossing candy in the air and catching it in the mouth) can demonstrate a talent useful to the story.

- Status. The type of food a character eats or prepares, whether hobo stew or truffles, may indicate the character’s status or wealth in the society. An author may also flip that script for an amusing or shocking contrast.

- Personality. Discussion about food, or the manner in which a character eats food, can unveil a character’s personality traits. Does the character slurp soup, season food before tasting, eat all the carrots before touching the potatoes, chew very slowly, slice the meat into many pieces before consuming one, etc.? How a character deals with food tells readers about the character’s general behavior patterns.

- Thoughts. Delicious food often reduces inhibitions, prompting people to say what they really think. This is particularly true as characters imbibe alcohol.

- Dialogue. People talk while eating, and a shared meal gives characters a chance to converse. This dialogue, like all fictional dialogue, must serve a purpose. It must reveal something about a character or must advance the plot, or both.

- Prop. The mechanics of food and drink consumption—sniffing, licking lips, arranging a napkin, cutting, lifting to the mouth, blowing to cool hot food, chewing, savoring, swallowing, etc.—help break up dialogue with action. A character may use an eating utensil to illustrate or emphasize a point.

- Relaxation. A quiet meal can serve as a low-tension scene separating two high-action scenes. It gives the reader a chance to catch a breath while characters catch a bite.

- Conflict. A meal may afford the opportunity for characters to confront each other over a disagreement. They may argue, or even fight.

- Symbolism. An author may use any type of food or drink to symbolize something else. If a character keeps coming back to a particular type of food, and it’s either described or consumed in a different way each time, chances are it symbolizes some aspect of a change in the character.

Unlike us, fictional characters don’t need food to survive, but a story might require a character to eat anyway.

Don’t know about you, but this discussion of food has made me hungry. It’s off to the kitchen for—

Poseidon’s Scribe