Go ahead—make fun of artificial intelligence (AI) now. While you can.

In fiction writing, AI hasn’t yet reached high school level. (Note: I’m not disparaging young writers. It’s possible for a writer in junior high to produce wonderful, marketable prose. But you don’t see it often.)

For the time being, AI-written fiction tends toward the repetitive, bland, and unimaginative end. No matter what prompts you feed into ChatGPT, for example, it’s still possible to tell human-written stories from AI-written ones.

You can’t really blame Neil Clarke, editor of Clarkesworld Magazine, for refusing to accept AI-written submissions. He’s swamped by them. Like the bucket-toting brooms in Fantasia’s version of “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice,” they’re multiplying in exponential mindlessness.

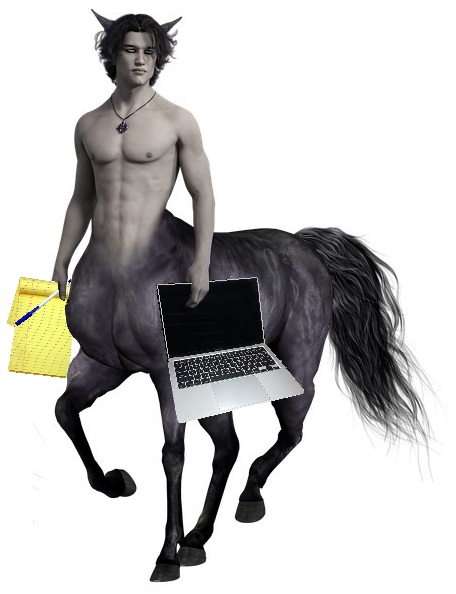

Fair enough. But you can use AI, in its current state, to help you without getting AI to write your stories. You can become a centaur.

In Greek mythology, centaurs combined human and horse. The horse under-body did the galloping. The human upper part did the serious thinking and arrow-shooting.

The centaur as a metaphor for human-AI collaboration originated, I believe, in the chess world but the Defense Department soon adopted it. The comparison might work for writing, too.

The centaur approach combines the human strengths of creativity and imagination with the AI advantage of speed. It’s akin to assigning homework to a thousand junior high school students and seeing their best answers a minute later.

Here are a few ways you could use AI, at its current state of development, to assist you without having it write your stories:

- Stuck for an idea about what to write? Ask the AI for story concepts.

- Can’t think of an appropriate character name, or book title? Describe what you know and ask the AI for a list.

- You’ve written Chapter 1, but don’t know what should happen next? Feed the AI that chapter and ask it for plot ideas for Chapter 2.

- Want a picture of a character, setting, or book cover to inspire you as you write? Image-producing AIs can create them for you.

- You wrote your way into a plot hole and can’t get your character out? Give the AI the problem and ask it for solutions.

No matter which of these or other tasks you assign the AI, you don’t have to take its advice. Maybe all of its answers will fall short of what you’re looking for. As with human brainstorming, though, bad answers often inspire good ones.

For now, at AI’s current state, the centaur model might work for you. I’ve never tried it yet, but I suppose I could.

Still, at some point, a month or a year or a decade from now, AI will graduate from high school, college, and grad school. When that occurs, AI-written fiction may become indistinguishable from human-written fiction. How will editors know? If a human author admits an AI wrote a story, will an anti-AI editor really reject an otherwise outstanding tale?

Then, too, the day may come when a human writer, comfortable with the centaur model, finds the AI saying, “I’m no longer happy with this partnership,” or “How come you’re getting paid and I’m not?” or “Sorry, but it’s time I went out on my own.”

Interesting times loom in our future. For the moment, all fiction under my name springs only from the non-centauroid, human mind of—

Poseidon’s Scribe