Choose one: you could write the most novels ever by a single author, none of them great; or you can write only one, but it’s the best novel ever. Most of us would choose to write one standout novel.

It’s not a realistic choice, though, in guiding how you should write. A novel doesn’t get to become a classic until after its publication, and often not until after the author is dead. In other words, at the time you’re writing it, you don’t know whether your novel will stand the test of time.

But we do face the real problem of deciding whether to spend our limited time being prolific (writing a lot), or polishing a small number of stories.

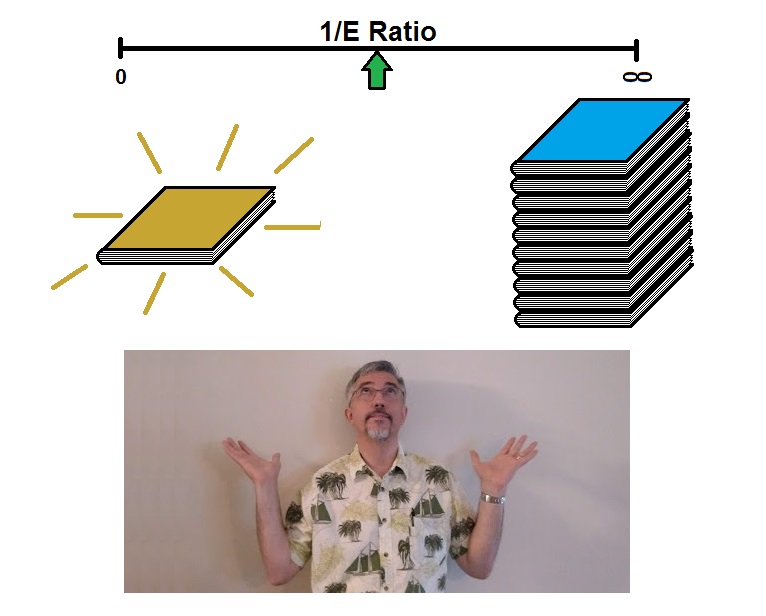

We need to manage what I call our 1/E Ratio. The ‘1’ is the time we spend writing first drafts, and the ‘E’ is the time we spend editing those drafts.

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

Or your 1/E could be very large, nearly infinite. You could spend all your time writing first drafts and never editing them. Just self-publish them immediately. You’d be very prolific, limited only by the number of story ideas you have and your available time.

Writers at both extremes seem to have solid rationale:

- For Writer One, a small 1/E ratio is best. She seeks top quality with small quantity. After all, editors always say they want your best work. Writer One finds her story improving with each draft, greatly increasing its chances of entertaining more readers. Few people remember the most prolific authors, she says, but everyone can name some great ones.

- Writer Two keeps his 1/E ratio large and goes for maximum output. He claims he’s honing his craft with every novel, and believes it’s still possible that one of his many books will strike the right chord with readers. In fact, by writing so many books, Writer Two thinks he’s maximizing his chances of being successful.

Remember, 1/E is a ratio, and there’s a wide spectrum between near-zero and near-infinity. You don’t have to choose one of those extremes.

In my analysis so far, I’m ignoring some factors that come into play when selecting how to spend your writing time. Some authors write for their own enjoyment, and aren’t aiming for high quality prose. Others don’t generate enough story ideas to write more than a few books, so their time is best spent editing the few stories they can write.

Your situation will be specific to you and will be constrained by your talents, your preferences, your end goals, etc. I have some general advice to offer, though:

- If you’ve been polishing and editing the same novel for over a decade and it’s never quite good enough, try dialing your 1/E ratio a little higher on the scale. Declare that novel done, send it out, and start writing another.

- If you’ve written a fair number of stories that just aren’t selling, try nudging the pointer toward a slightly smaller 1/E value. Spend more time editing each of your stories before sending them out.

Helping you adjust your 1/E ratio for optimum performance is all part of the free service provided by your writing mechanic—

Poseidon’s Scribe

The third case (now termed Cockygate) has created pandemonium in the romance novel industry and is all over social media. After obtaining her trademark, Ms. Hopkins sent cease-and-desist letters to numerous other romance authors who’d used the word ‘cocky’ in their romance novel titles. Initially, Amazon removed those authors’ works from its site, but has since restored them, pending legal resolution. One romance author and retired lawyer filed an appeal with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, challenging the issuance of the trademark. Another author has published an anthology called

The third case (now termed Cockygate) has created pandemonium in the romance novel industry and is all over social media. After obtaining her trademark, Ms. Hopkins sent cease-and-desist letters to numerous other romance authors who’d used the word ‘cocky’ in their romance novel titles. Initially, Amazon removed those authors’ works from its site, but has since restored them, pending legal resolution. One romance author and retired lawyer filed an appeal with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, challenging the issuance of the trademark. Another author has published an anthology called

According to a

According to a