Today’s lesson is: how to write a book that becomes known as a classic. Good news—we can identify some attributes of classic literature. Bad news—no book becomes a classic in the author’s lifetime, so you won’t find out if your book made the list until after you’ve been dead awhile.

I’ve blogged before about the attributes of good, quality short stories, but today’s question is about the few books that attain true classic status. These must pass a more stringent test.

I’ve blogged before about the attributes of good, quality short stories, but today’s question is about the few books that attain true classic status. These must pass a more stringent test.

Easy, but Unsatisfying Definition

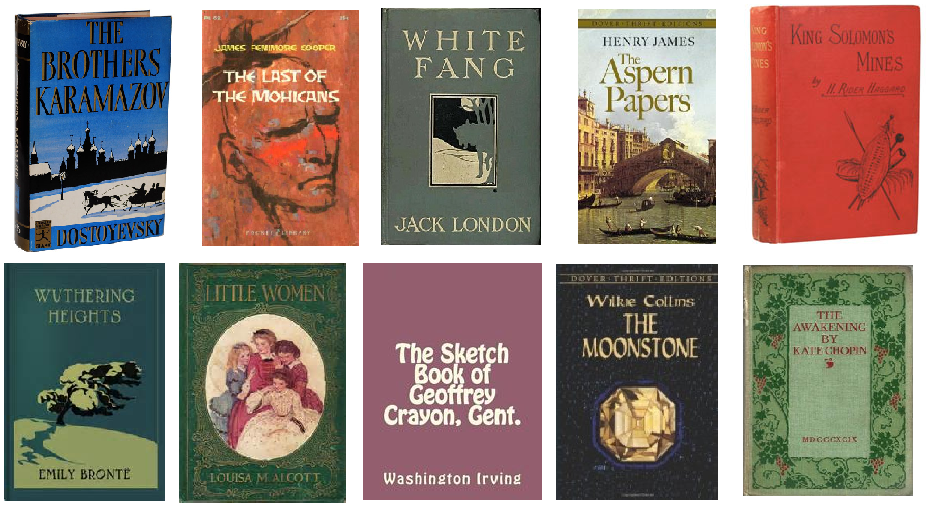

Many people say that a classic is that which endures, stands the test of time, and which people still read long, long after the author is dead. In his book Antifragile, Hassim Taleb states that you can make a rough prediction about how long a book will remain in print. The average time a book will remain in print from this point on is equal to the time it has been in print so far.

To me, this definition of a classic, though true, doesn’t really settle anything. It begs the question, why do readers today still want to read this book? Let’s accept that a classic must endure, but I want to explore why this is so.

Other Folks’ Definitions

I’m not the first to knock on the door to this party; in fact I’m way past fashionably late. Many people before me have come up with great definitions of what makes a classic.

- Italo Calvino says you can’t feel indifferent to a classic. That definition makes it a personal connection between book and reader. However, that’s not so useful to an author trying to write a classic.

- Blogger Chris Cox builds on Mark Twain’s definition. There are two kinds of classics, those we’re embarrassed not to have read yet, and those we nag others to read. Funny, but again it concentrates on the reader-to-book connection.

- The French literary critic Charles Augustin Sainte-Beuve said the author of a classic “….has enriched the human mind…caused it to advance a step; who has discovered some moral and not equivocal truth, or revealed some eternal passion in that heart where all seemed known and discovered…who has spoken to all in his own peculiar style, a style which is found to be also that of the whole world, a style new without neologism, new and old, easily contemporary with all time.” This is closer to what I’m looking for—let’s hold those thoughts.

- Goethe said it’s not a classic because it’s old, but because it’s forever new. I like that one.

- Some blog commenters have said a classic had some impact or effect on the age in which it’s written. That may be true for most classics, but not all such books endure.

- Others say a classic is that which is new or innovative in its time. But, again, it’s not clear to me why such books would necessarily stand the test of time.

- Jonathan Jones, a writer for The Guardian, says a classic must be elastic. That is, it endures despite plagiarism, satire, criticism, etc. Hassim Taleb would hasten to add that such pummeling of a classic makes it stronger, more enduring, and to use his word, antifragile. I like this attribute too, but it’s more about the reaction to a book rather than the writing of it.

My Definition

Borrowing the attributes I like and rejecting the rest, here are my rules. A classic for the ages must:

- capture its time

- be well written

- say something profound and permanent about the human condition

There you have it. Write your book that way, and it might become a classic someday. Something for your great-grandchildren to enjoy. Currently at work on a classic, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.