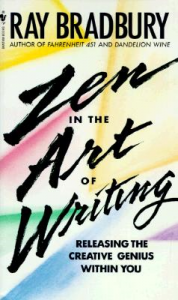

You long to write stories like the ones you enjoy reading, but doubt you could. Writing seems tedious and you think you lack the required expertise. You just know you’d get bored and disillusioned after a few pages. The late author Ray Bradbury offered some advice that might help you.

In his 2001 lecture at The Sixth Annual Writer’s Symposium by the Sea, sponsored by Point Loma Nazarene University, he provided great tips about writing, including these two gems:

- Make a list of ten things you love, madly, and write about them. Make a list of ten things you hate, and write about killing them. Make a list of the ten things you fear, and write about them.

- Don’t write self-consciously, commercially, what will sell. Find the deep stuff, your inner self. Don’t ask what will sell. Ask who am I?

Exercise

First, you’ll be jotting down three lists of ten items each—things you love, things you hate, and things you fear. No one else will see these lists. Think of ten as a minimum number. Bradbury chose ten to prod you to think beyond the first few easy ones. You’ll be stretching to reach ten, and that’s the point. He’s trying to get you to dive down to your essence, your core.

Given that introduction, I suggest you do the exercise now. Really. Now. Stop reading this and generate your three lists of ten each. I’ll wait until you finish.

Intermission

After the Exercise

All done? Good. You’ve got lists of things you love, things you hate, and things you fear. For every item on all three lists, you feel some level of passion. Positive feelings of adoration accompany each item on the ‘love list.’ Feelings of anger boil up in response to those on the ‘hate list,’ and feelings of dread ooze out of those on the ‘fear list.’

The lists, then, provide two things you’ll need—subjects to write about, and feelings to sustain you while writing.

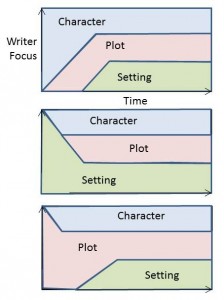

Subjects

As a fiction writer, you don’t have to write about the exact objects of love, hate, and fear you listed. Perhaps it’s better if you don’t. Use a stand-in, a metaphor, something to represent one or more of the specific things listed.

Say you wrote ‘my spouse’ on the list of things you love, and decided to write on that topic. I’m suggesting you shouldn’t write about your own spouse, but rather write about a character’s love for that character’s spouse. Readers won’t know it’s really your own spouse—they’ll just note the tenderness with which you convey the love.

Caution

I offer a quick note about the list of things you hate. Don’t turn your writing into an angry manifesto. The list should serve as a catalyst for writing, not a prelude to violent action. Take out your vengeance on fictional characters only.

Feelings

The real power of Bradbury’s advice comes from the intense emotions you feel about every item on each list. Those emotions should make it easier (1) to write ‘in the flow,’ (2) to know, at any point, what to write next, (3) to stay enthused about the project until completion, and (4) to infuse your writing with spirit. Your strong feelings about the subject will pass through to readers.

Digging Deep

The other piece of Bradbury’s advice really nails it. “Find the deep stuff, your inner self. Don’t ask what will sell. Ask who am I?” By listing things you love, hate, and fear, you’re getting at your essence, your basic humanity, your soul. Write from out of that core, and your words will ring true. They’ll shine.

Writing from the heart, with fervor, gives you a better chance of reaching readers, too, especially those who care about the same things, readers whose own love/hate/fear lists—if they made them—would reveal some commonality with yours.

Thanks to Ray Bradbury, you’ve got the tools you need. Your lists have fired the coals of an inner boiler. That high-pressure boiler powers a potent writing machine—you. The steam is up, the throttle is open. Go! Nobody can stop you now, least of all—

Poseidon’s Scribe