According to news accounts here, here, and here, divers will use a special diving suit (called the Exosuit) to explore off the coast of Antikythera Island near Greece. The site is a debris field left by a Roman merchant ship estimated to have sunk around 60 B.C. in 200 feet of water.

They’ll be looking for more pieces of “the world’s oldest computer.” It’s a geared calculating machine, discovered by divers in 1900. No one credited the ancient Greeks with much knowledge of gear technology, until the discovery of this machine.

They’ll be looking for more pieces of “the world’s oldest computer.” It’s a geared calculating machine, discovered by divers in 1900. No one credited the ancient Greeks with much knowledge of gear technology, until the discovery of this machine.

The question you’re probably wondering is, why now? The mechanism has been known about for more than a century. Why are scientists and explorers suddenly interested in finding out if they are missing some parts of the machine, or if they already have extra pieces and there were two devices aboard the ship? What prompted this new expedition?

I might have had something to do with it.

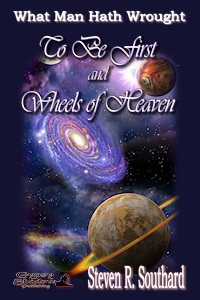

You see, I wrote a story about the Antikythera Mechanism called “Wheels of Heaven,” and it just got published (by Gypsy Shadow Publishing) a couple of months ago. In my tale, I explain what the machine is and how it came to rest at the bottom of the Aegean Sea.

You see, I wrote a story about the Antikythera Mechanism called “Wheels of Heaven,” and it just got published (by Gypsy Shadow Publishing) a couple of months ago. In my tale, I explain what the machine is and how it came to rest at the bottom of the Aegean Sea.

You’d have to agree this can’t be a coincidence. Obviously someone read my story and got to thinking, “I wonder if he’s right? Is that how it happened?”

No one associated with the expedition is likely to admit it, of course. They might even deny it if asked. After all, no scientist wants to confess to being inspired by a mere fictional short story.

But we know the truth, don’t we? The connection is too strong to ignore. They can refute it all they want.

At this point you’re probably curious what the fuss is all about. You can purchase “Wheels of Heaven” along with another story “To Be First” here, here, here, and other places too. Sail along on the ship Prospectus with the Roman astrologer Drusus Praesentius Viator, and a common sailor from Crete named Abrax as they argue over whether the machine can tell the future.

Once again we see mysterious parallels between the breaking news of today’s world and the worlds depicted in my stories. A few weeks ago, I told you about the upcoming landing on a comet, an event similar to the one in my story “The Cometeers.”

The question we must ask, then, is which will be the next story of mine to have some strong link to the news headlines? Which of my other books of alternate history will prompt the next scientist, explorer, or engineer to undertake a grand investigative effort? You can offer your own answer to this question by leaving a comment to this blog post.

Strange how this keeps happening, isn’t it? If you want to know the science and technology news of tomorrow, simply to turn to the works of—

Poseidon’s Scribe

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.

Four vital and weighty questions. An average blogger would shrink from the challenge of answering them all in one short post. But you’ve surfed to no ordinary website. I laugh at such challenges, or at least chuckle in a menacing way.

Four vital and weighty questions. An average blogger would shrink from the challenge of answering them all in one short post. But you’ve surfed to no ordinary website. I laugh at such challenges, or at least chuckle in a menacing way.