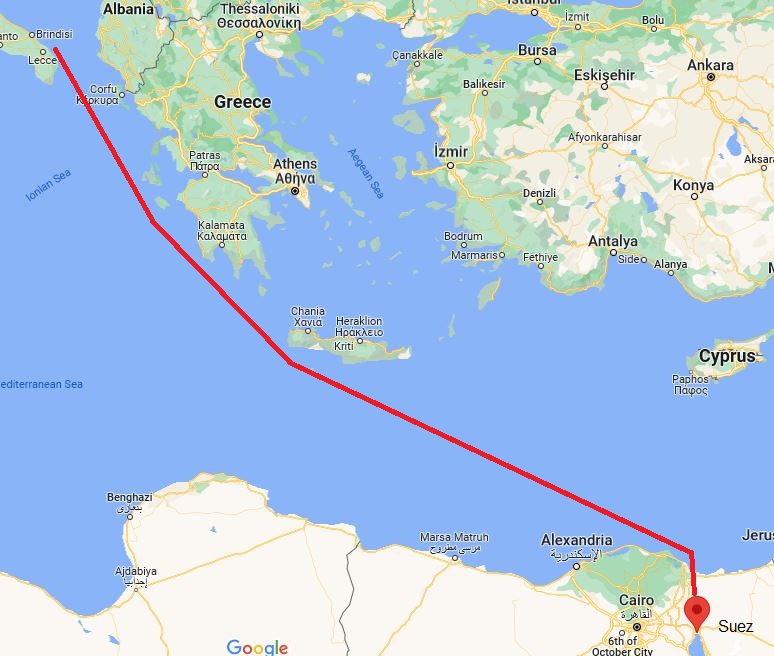

Thank you for joining me on my global blog tour. We’re following the route taken by Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s Around the World in Eighty Days, 150 years after its publication.

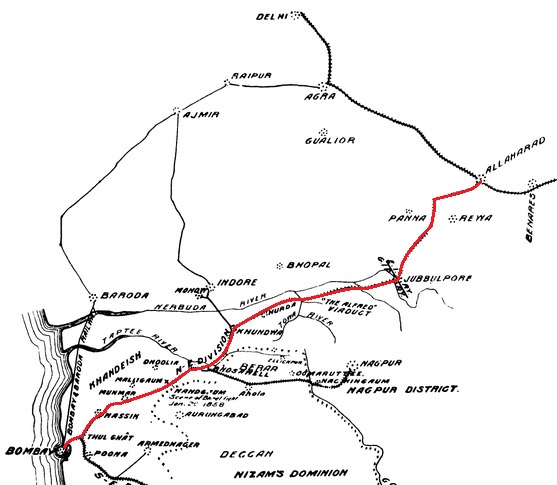

Since leaving Mumbai (called Bombay in those days) we’ve reached Allahabad. Much has happened since then, so let’s catch up with the action.

On the train, Fogg met Sir Francis Cromarty who, besides being countryman and a whist player, knew India well and became Fogg’s traveling companion. At 8:00 pm on October 21, the train stopped beyond Rothal near Kholby. (Don’t bother looking for place names on the map. I’ll explain later.) Track had not yet been laid down between there and Allahabad. Determined to forge ahead, Fogg bought an elephant and the services of a guide.

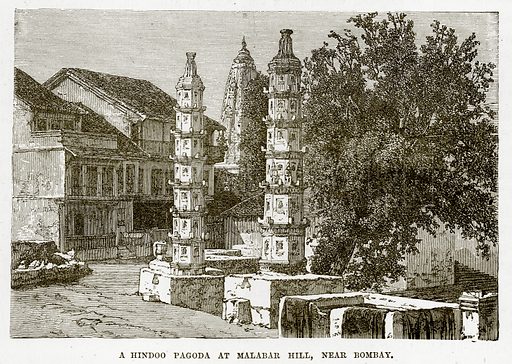

They rode the elephant past the village of Kallenger on the Cani River. Witnessing a procession of Brahmins, they found out a young princess named Aouda was to be put to death. Her husband, the rajah, died, and the practice of suttee (or sati) demanded her sacrifice, which would occur in the village of Pillaji.

Aghast, Fogg decided to try to save her, and it’s Passepartout who actually did. Along with Aouda, the group arrived in Allahabad. No longer 2 days ahead of schedule, he had then traveled 6835 miles, covering 27.8% of the distance in 27.5% of the time.

Verne had stayed true to geographical facts up to this point. However, as noted in Nicholas Whyte’s informative website, the villages of Rothal, Kholby, Kallenger, or Pillaji never existed. Nor is there a Cani River. It appears Verne made them up.

Why might he have done that? He must have had access to a route map of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway, which included accurate village and river names. However, he intended to describe specific places in negative terms (failure to complete railroad lines, practicing suttee), so may have made up fictional names for that area to avoid lawsuits.

By the way, suttee/sati was banned in British India since the 1840s, and has been illegal in modern India since 1987. However, some widows even in the last twenty years have voluntarily committed suicide on their husband’s funeral pyres.

At the time of the novel, Allahabad’s population numbered about 144,000. Today, it’s over 10 times that, 1.54 million. Modern travelers don’t need 4 days to get from Mumbai to Allahabad. Without elephants or princesses, you can take a 2-hour flight between those cities.

I, for one, am glad Aouda joined us on our trip now. It’s about time this journey included a woman. Speaking of that, a female protagonist stars in my new ebook, 80 Hours. You may purchase it at Tolino, Vivlio, Amazon, Apple Books, Barnes & Noble, Rakuten Kobo, and Scribd.

Our traveling party is cutting it close. We’re due in Kolkata tomorrow to make the steamer. Will we make it? That answer is known only to—

Poseidon’s Scribe