Could you write a million words a year? That’s the equivalent of a novel a month. Meet today’s interview guest, Rachel Aukes, who aspires to write a million words a year and has already published over forty novels. I met Rachel at ICON (an eastern Iowa scifi conference) in 2023 and saw her there again in 2025. Buckle up for a fast-paced interview, one that barely registers in her million-word count.

Bio

Rachel Recker, writing as Rachel Aukes, is a bestselling author known for gritty science fiction and chilling horror that explore humanity at the edge. She’s written over forty novels, including 100 Days in Deadland—a zombie apocalypse retelling of Dante’s Inferno that was named a “Best of the Year” pick by Suspense Magazine—and The Lazarus Key, a high-octane sci-fi thriller featured by The Big Thrill magazine. One of Wattpad’s first Stars, her stories have reached over eight million readers around the world.

Rachel is a licensed pilot, former tech executive, and lifelong comic book collector. When not plotting the end of humanity, she hikes state and national parks with her dog.

Interview

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Rachel Aukes: Like many writers, storytelling is in my blood. I was fascinated with stories as a child, and I wrote quite a bit. However, life led me on a meandering journey that eventually brought me back to my original passion. While I’m thankful for my life’s experiences, I’m so glad to be writing full time.

P.S.: Tell us about your comic book collection. Do you prefer certain comics, or a variety? Does your interest in that medium (high adventure, vivid graphics, brief speech balloons) influence your fiction in some way?

R.A.: Like most kids growing up in the 80s, I began with Marvel and DC. My childhood collection grew to over 3000 comics, though now I tend to read comics digitally to save physical space and invest in high-quality graded comics.

Comics have absolutely impacted my punchy, action-driven writing style. I can pack a lot of storyline in a scant ten pages.

P.S.: With over 500 ratings on Amazon, your novel Expendable, first in the Redline Corps series, has readers enthralled. Tell us about the main character, Liv Reyes, and the book’s premise.

R.A.: The idea of Liv came about from seeing a survey of Gen As who overwhelmingly aspire to be social media influencers (yikes, but that’s a debate for another day). So, I decided to create an influencer as a main character who gets drafted as a war correspondent with the task to put a positive spin on the war.

P.S.: Having published over forty novels, you’re one of the most prolific authors I’ve ever interviewed. Your website states your personal goal of writing a million words this year. That’s over 2700 words per day, well beyond the average for the (now closed) high-speed Nanowrimo challenge. Will you achieve your goal? How do you write so fast?

R.A.: Writing is my career, and I treat it like a job, setting regular hours and deadlines. I think some writers get into this mindset that writing should only take place while inspired, but that’s hogwash. Sure, story ideas and characters come from inspiration, but a story comes from hard work, craft, and dedication.

I unfortunately won’t hit the goal this year due to a lot of personal changes in my life right now, but I definitely plan to hit it next year!

P.S.: Congratulations on earning your pilot’s license. Do you fly often? Has that knowledge and skill helped you in your writing?

R.A.: Thanks! I don’t fly often right now, but I use the ideas and concepts of flying through most of my books. Taking the “write what you know” literally, nearly every book has an aviator character.

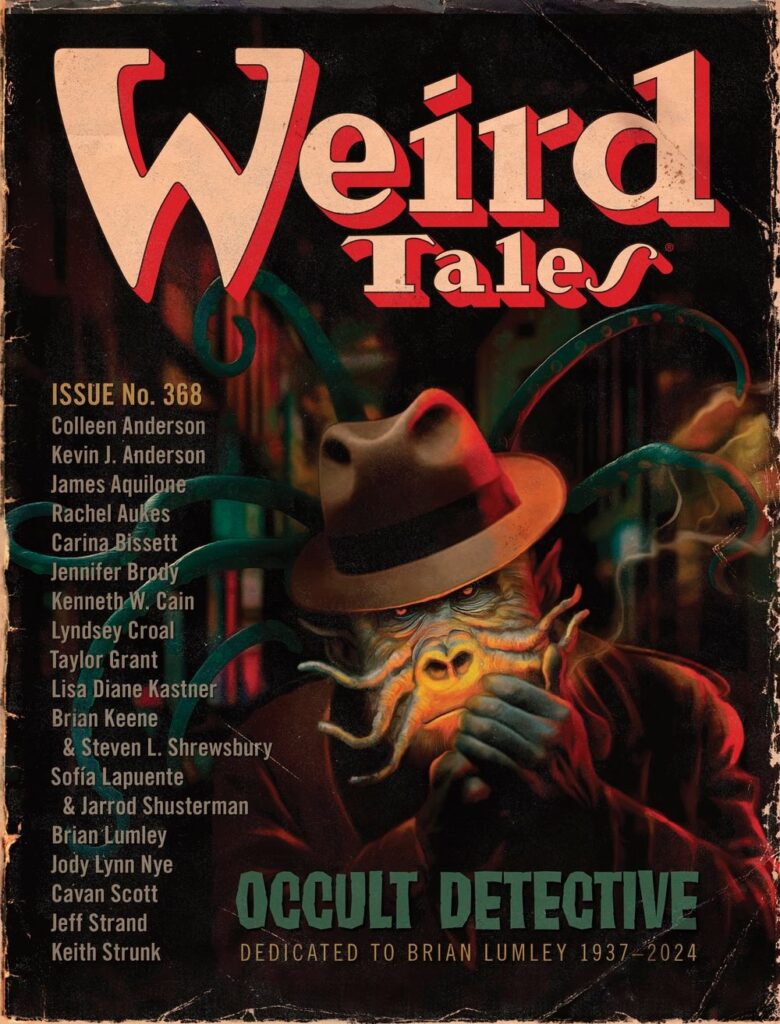

P.S.: Your short story, “Three-Headed Problem” appears in Weird Tales #368 – The Occult Detective Issue. Tell us about this story and what prompted it.

R.A.: I was catching up with Jonathan Maberry (who’s a great guy and an amazing writer) as a recent conference, and he mentioned about my writing a story for Weird Tales, which is a magazine I adore. The next issue with an opening was the Occult Detective issue. I came up with the idea of Roy Stinson, the best damned detective in hell, who’s the most tenacious PI in the underworld. His day job takes a twist when someone steals Cerberus’s favorite bone. And without his treat, the hound refuses to stand guard at the infernal gates. So, all hell will break loose if Roy doesn’t solve the crime and fast.

P.S.: Is there a common attribute that ties your fiction together (genre, character types, settings, themes) or are you a more eclectic author?

R.A.: I only write speculative fiction, covering primarily the science fiction, fantasy, and horror genres. Other than that, I’ve written everything from current day apocalypse to far-future galactic wars. An underlying theme in most of my stories, though, is humanity on the brink of disappearing.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

R.A.: The easiest are the ideas. I have SO many story ideas that I desperately want to write, but don’t have the time, which leads to the most difficult part: finding the time and energy to write as many of those ideas as I can (and to write them as good as I can).

P.S.: You own your own publishing company, Waypoint Books. How and why did you come to create a one-woman publishing company?

R.A.: I wanted to have a corporation set up for my self-publishing activities. I also felt it looked more professional to have books listed under a “real” publisher than under my name, especially since I write under a pen name.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

R.A.: I’m co-writing a progression science fiction series with JN Chaney that we’re launching in early 2026. The series, Infinity Upgrade, is about a blue-collar guy getting a highly advanced, experimental AI shoved into his brain without his consent. Needless to say, it brings a lot of problems with it.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring authors?

Rachel Aukes: Just write. It’s as simple as that. Don’t let anything else cloud your mind. If you want to write, then do it. The more you write, the better you’ll get. Let the complications, like deciding if you want to publish and then how to publish, come later. When you’re new at this game, focus on the fundamentals. And it all boils down to the writing.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thank you, Rachel. Great advice!

Web Presence

I wish readers and fans the best of luck keeping up with Rachel. She writes faster than we all can read. You can learn more about her at her website, on Facebook, Amazon, and Goodreads.