Forget your high school chemistry classes. We’re talking fictional character chemistry here—human reactions. More complicated, more dramatic, and potentially more explosive.

You know it when you see it on TV or in the movies. Two actors with great chemistry. Somehow, their interaction sizzles and sparks, even ignites into figurative flame.

Written stories, the good ones, portray this chemistry too. When a reader knows two characters separately, and they’re about to get together and interact, the reader anticipates something big will happen.

As a writer, you serve as the catalyst for this chemical reaction. You make it happen, and the only things consumed in the process are your time and some Kleenex.

How do you concoct that chemistry? Author K. M. Weiland wrote a marvelous blogpost explaining the process and giving wonderful examples. After reading my brief summary below, study her post for a better and more complete description. What follows is her process, abbreviated and put in a different order, and in my words.

Connect to the Plot

K. M. Weiland listed this last, but to me it comes first. The scenes where your characters interact must serve the plot. They must move the story along. If you write a scene with great chemistry, but it doesn’t advance the story, you’ve taken an unnecessary tangent and written a darling you must kill. Whether you’re a plotter or a pantser, make sure the scenes propel the action forward.

Put Engaging Characters in the Crucible

The chemistry works best with well-defined characters. If you’ve introduced the characters by themselves earlier, then the reader anticipates the coming interaction. Give your characters different (and very clear) motives, desires, and personalities. These traits needn’t directly oppose each other, though that helps. Perhaps the characters share a common goal, but differ on the manner of achieving it. Exploit all differences.

Alternate the Give and Take

As the characters banter, fluctuate between agreement and disagreement. Give one character the upper hand, then the other. You’re striving for equal yin-yang balance here. Weiland calls it ‘the dance of opposition and harmony,’ a perfect metaphor.

When catalyzing this chemistry, don’t limit yourself to dialogue alone. Give your characters things to do, actions to take. These actions can illustrate and emphasize what they say, or tend to contradict their words, depending on your intent. For example, if a character says something harsh, perhaps she can do something pleasant to soften the impact.

Allow an Out-of-Character Moment

Consider letting Character A say or do something unexpected, beyond A’s usual role. Not only will this surprise the reader, but it will jar Character B, forcing B to adapt to the shifting dynamic.

Let Them Grow

The interaction may well expose character flaws, forcing self-examination. One or both characters may change as a result of their confrontations, which may serve to round out the rough edges of their personalities. A great example of this is C.S. Forester’s 1935 novel The African Queen, and the 1951 movie of the same name. In the course of the story, Charlie Allnutt becomes more confident, daring to accomplish actions for a cause greater than himself. Rose Sayer backs off some of her strict religious intolerance. Both grow as people.

This concludes today’s chemistry lesson. All you mad scientists—er, I mean, budding writers—can now follow the formula for creating great character chemistry, as revealed by K.M. Weiland and—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

Violent interactions can take many forms beyond individual combat. These include war, rape, terror, shooting sprees, etc. This post focuses on fights between two characters, but many of my suggestions apply to other situations.

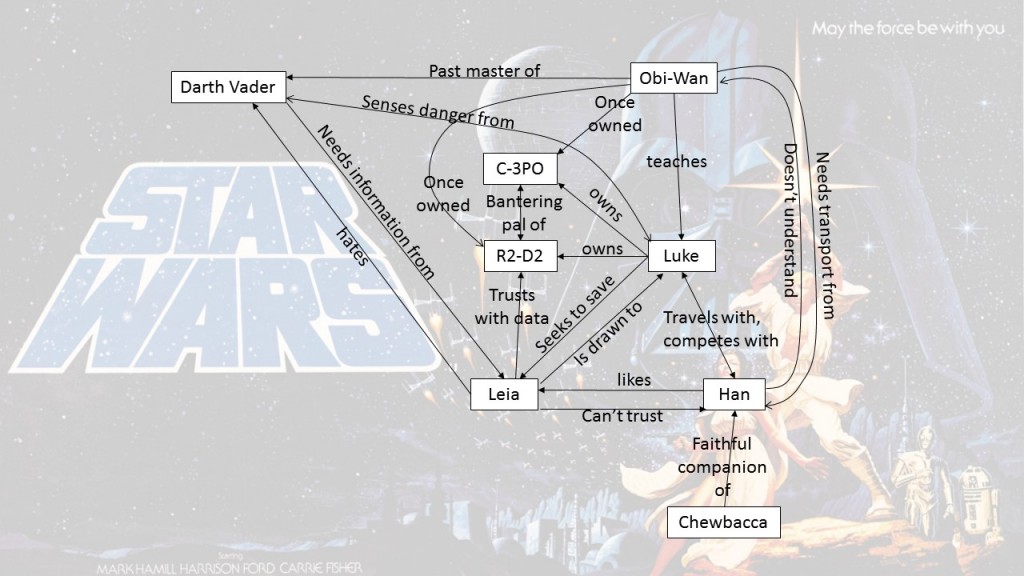

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.

The one I’m showing here, for the first Star Wars movie, A New Hope (Episode IV), is for illustrative purposes only and is not complete or necessarily accurate. My only intent is to show one possible example for a case familiar to most readers. To see many other sample Character Relationship Maps, do an Internet search for that term and click on images.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.