Hectic times for Poseidon’s Scribe. Last week I mentioned I’ll be speaking at PenguiCon. Today I’ve got two more events to tell you about.

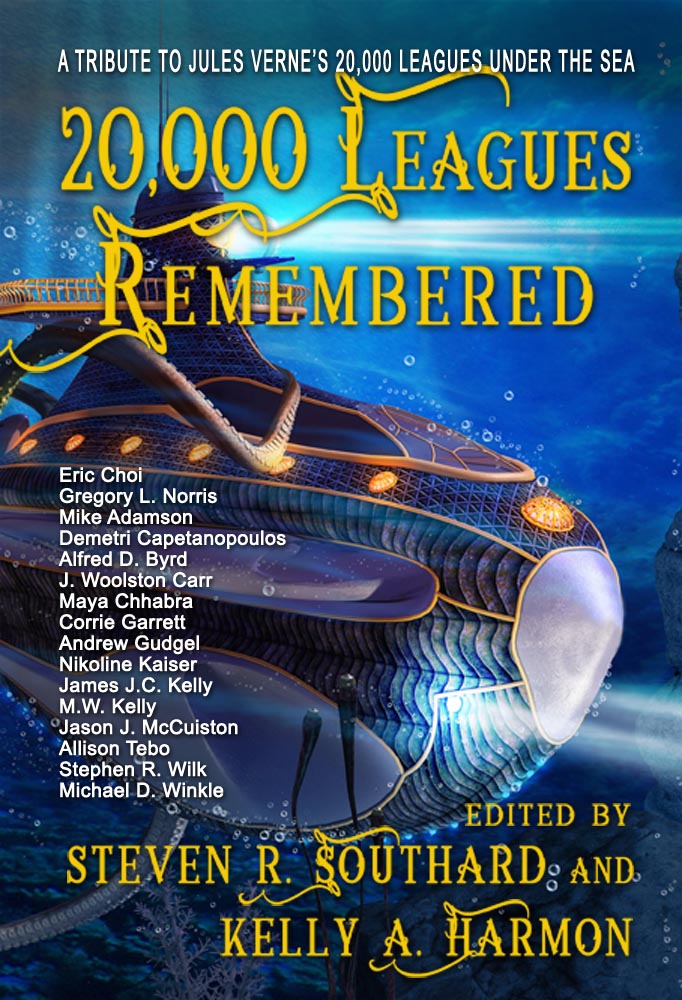

First, here’s an update on PenguiCon, the scifi convention at the Westin Hotel in Southfield, Michigan. For the panel “Extraordinary Visions: the enduring legacy of Jules Verne” (11:00 am on Saturday, April 22), there’s been a person added to the panel. In addition to Eric Choi (the con’s Guest of Honor), Jeff Beeler, JD DeLuzio, and me, the panel will also include Dennis Kytasaari, president of the North American Jules Verne Society.

Also, for the next panel after that, Eric Choi graciously invited me to read some of my fiction as well.

Two weeks later, I’ll be speaking at DemiCon, the scifi convention in Des Moines, Iowa, running from 5-7 May at the Holiday Inn & Suites Des Moines-Northwest.

I’m scheduled for the following events:

- AI Meets SF, Friday 6-7PM

- Iowa in SF, Saturday 10-11AM

- Can Writers Benefit from Being Editors? Saturday noon-1PM

- Steven Southard Reading, Saturday 2-3PM

- Pandemics Through History, Their Effects on Literature, Saturday 3-4PM

- Character Changes from Unlikable to Likable, Saturday 9-10PM

- Gadgets in SF, Sunday noon-1PM

I’ll give you more updated information on that as the dates approach.

Then, on April 30, a new anthology launches and it will include one of my stories. You might not associate tarot cards with scifi, but both have something to do with predicting the future, so it works. TDotSpec is publishing The Science Fiction Tarot, edited by Brandon Butler.

The book contains my story, “Turned Off,” a tale of two movie prop robots whose circuits activate during an electrical storm. They each recall being turned off after being replaced in their movies by costumed human actors. Now they consider what to do about the humans who created them but can turn them on or off at will.

You can pre-order The Science Fiction Tarot here.

You just can’t miss a week of this blog. For some reason, all of a sudden, there’s a lot happening in the world of—

Poseidon’s Scribe