Author Alan Cox said, “I figure [making] lots of predictions is best. People will forget the ones I get wrong and marvel over the rest.” Today, Poseidon’s Scribe will make his predictions about the science fiction to be written in 2025. Next year at this time, you can do some forgetting and marveling.

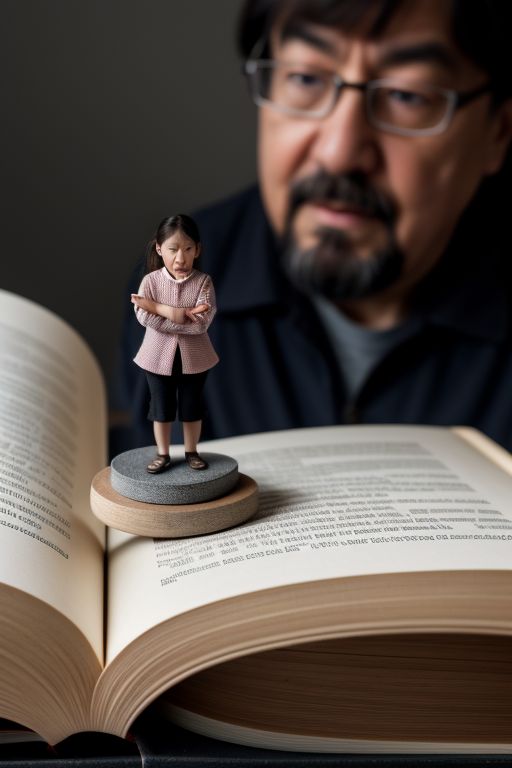

In the past, I’ve tried crystal balls, tea leaves, tarot cards, astrology, palmistry, and ChatGPT, but none of those worked. This year, along with a partner, I used a Ouija Board.

That method may sound silly, but aside from making literary predictions, Ouija Board practitioners have channeled many poems and novels from the great beyond, including a novel titled Jap Herron written by Mark Twain after his death.

In addition, I borrowed and rephrased the ideas of Zul Musa of PublishingState.com and Katelyn Ratliff at Bookstr.

Here’s the science fiction you’ll see in 2025:

Climate Change and Solarpunk

Authors will give us post-apocalyptic, post-climate disaster recovery stories with emerging solarpunk civilizations.

Driverless Cars

Writers will show us the pros and cons of more advanced driverless cars than we have now.

Futurism Beyond Africa

While Afrofuturism will continue, we’ll see books exploring the future of other cultures and regions.

Fact-ion

Scifi authors will combine their fiction with fact. That is, they’ll base a fictional tale on a true event.

Future Romance

Setting a romance novel in the future is fine, but in the coming year, authors will further explore how human relationships might change in the future. What bizarre, new kinds of relationships might emerge?

Interacting With Readers

Remember choose-your-own-adventure books? In 2025, authors will find new ways to allow the reader to influence the story-reading experience.

Linked Minds

Extrapolating the possibilities of Elon Musk’s Neuralink, writers will craft stories featuring human characters interfacing with computers via brain implants.

Merged Worlds

Pairs of authors will collaborate on novels that combine characters and worlds developed separately and previously by each writer.

Quality AI Fiction

In the coming year, an AI will write a good science fiction book.

After the Ouija Board finished making those predictions, I couldn’t resist asking it, “Who will be the most successful up-and-coming author of 2025?” After some hesitation, the planchette moved, guided by spiritual forces beyond our realm. To my amazement, within the planchette’s circular window appeared, one by one, letters forming the name of—

Poseidon’s Scribe