Do women and men talk differently? Do they use different types of words and phrases, or speak about different topics? More importantly to you fiction writers, should you have your characters speaking differently depending on their gender?

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender.

This blog post comes with a giant disclaimer. I’ll be discussing general tendencies, not rules. Rather than concentrating on having a female character “talk like a woman,” focus instead on having her talk consistently with her personality, age, nationality, time period, upbringing, geographical location, and gender. In other words, the way your characters talk depends on a lot more than gender.

Let’s examine those tendencies:

Women characters tend to:

- Commiserate, sympathize, and seek to understand the emotions, when speaking about another person’s problem, to help the person not feel alone in suffering;

- Establish, when speaking to another woman, the degree of closeness (horizontally), to seek areas of agreement, perhaps by revealing a secret about herself, or a personal story, demonstrating her willingness to be vulnerable;

- Interrupt, when the other person tells a story, to ask questions to push the story forward, or even co-author the story;

- Ask more questions;

- Explain or justify their actions and decisions;

- Describe things and scenes by emphasizing appearance and other senses, using a full palette of color words;

- Look or ask for validation, approval, or agreement periodically as they speak; and

- Look directly at the face of the person they’re talking to, or listening to, alert for nonverbal emotion cues.

Men Characters:

- Offer a solution when discussing another person’s problem;

- Seek to establish the relationship, when speaking to another man, in a (vertical) hierarchy, through mild insults, jokes, and one-upmanship;

- Interrupt to tell his own story, when the other person tells a story;

- Make more suggestions and assertions rather than asking questions, but when men do ask questions, they’re specific and focused, not rhetorical;

- Talk about what they did or decided, without offering explanations or justifications;

- Describe things and scenes according to functions, directions, and numerical distances and quantities;

- State their facts directly without seeking approval or agreement, without significant concern about the other person’s reaction; and

- Gaze elsewhere when speaking or listening, rather than looking at the other person’s face.

Which gender talks more? Apparently, studies are inconclusive. Therefore, it makes sense to let a character be talkative if it fits that character, whether male or female. You can have interesting combinations of chatty characters paired with silent ones, or two loquacious ones, or two quiet ones.

For further information, there are some great blogs and articles out there, like this one by Kimberly Turner, this one by Rachel Scheller, and this article in Salon by Thomas Rogers.

Let me reiterate the disclaimer. Everything I’ve noted above is a general tendency, not a strict rule. Use the information sparingly and for guidance so your fictional characters sound realistic. If you carry this too far, you’ll end up with stereotyped characters. Let their speech style flow from who they are, rather than just their gender. It’s easy to find examples today of people who speak with the tendencies of the opposite gender without anyone else noticing, let alone caring.

I know this is a touchy subject. Still, if I’m to bring you the best guidance possible to aid you in your writing, I can’t shy away from controversy. I must boldly provide this information without worrying about charges of sexism. I cannot do or be otherwise; I must be—

Poseidon’s Scribe

A strategic plan is a detailed blueprint of how to achieve that mission. It assigns intermediate actions to complete, and dates when each action is to be done. It is a logical progression of steps toward the goal. It is achievable and actionable.

A strategic plan is a detailed blueprint of how to achieve that mission. It assigns intermediate actions to complete, and dates when each action is to be done. It is a logical progression of steps toward the goal. It is achievable and actionable. No, you protest. Those aren’t new. They’re just rehashes or remakes of old ideas, with some new flair added. They’re just old stories brought into modern times, well-used story lines put in a new setting, or known plotlines with the main characters’ genders reversed.

No, you protest. Those aren’t new. They’re just rehashes or remakes of old ideas, with some new flair added. They’re just old stories brought into modern times, well-used story lines put in a new setting, or known plotlines with the main characters’ genders reversed. Simply put, a MacGuffin is the protagonist’s goal. It can also be the goal of the antagonist as well. Perhaps they’re both pursuing it, or seeking to prevent the other from having it. It can be a tangible object, or an abstract idea.

Simply put, a MacGuffin is the protagonist’s goal. It can also be the goal of the antagonist as well. Perhaps they’re both pursuing it, or seeking to prevent the other from having it. It can be a tangible object, or an abstract idea.

Sure, you say, but those great authors don’t do anything but write. Writing is their day job. That may be true for many of the great authors, but few of them started great. Most had day jobs until their books sold well.

Sure, you say, but those great authors don’t do anything but write. Writing is their day job. That may be true for many of the great authors, but few of them started great. Most had day jobs until their books sold well.

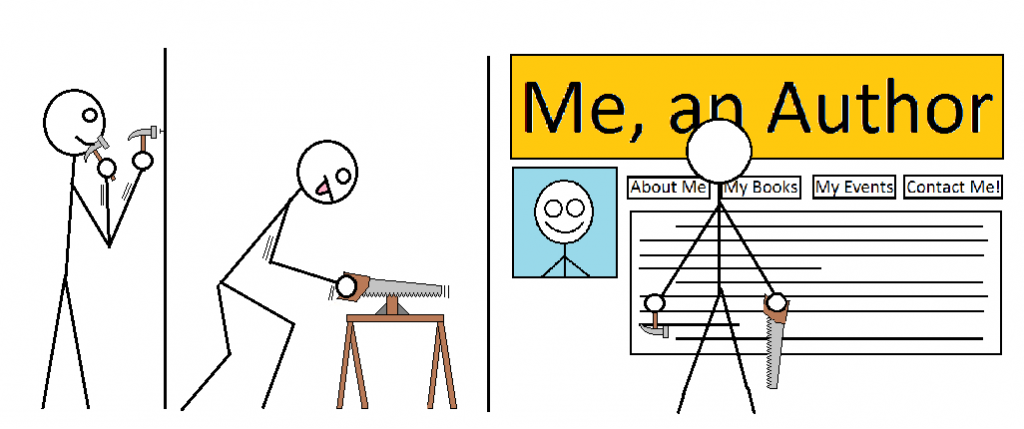

A website does at least the following things for you:

A website does at least the following things for you: