Some time ago, I posted about how to get yourself in the mood to write. Today I’ll come at it from a different slant and suggest you should write even when you’re not in the right mood.

We’ve all been there. There’s a task (say, writing) you should do, and it’s now the allotted time for it. However, you’re not in the mood. Something else has happened to put your mind in the wrong frame.

Typically, it’s some strong, negative emotion like anger or sadness. Someone or something has upset you and left you too distraught to do any writing. You can’t bear the thought of writing, can’t imagine sitting down at a keyboard, not at a time like this.

Your mind is filled with raw feelings, and you have no room for anything else. You can’t be creative, not now. You can’t get in the mind of a character right now, can’t be bothered with rules of English, or with choosing the right words. Besides, your novel is a comedy, and you’re feeling the opposite of funny.

Your mind is filled with raw feelings, and you have no room for anything else. You can’t be creative, not now. You can’t get in the mind of a character right now, can’t be bothered with rules of English, or with choosing the right words. Besides, your novel is a comedy, and you’re feeling the opposite of funny.

I suggest that this is a fine time to sit down and write. Why?

- It’s important to preserve the discipline, the habit, of writing. As we know, bad habits are easy to form, and good habits are easy to drop. If you skip a day of writing based on your bad mood today, it’s that much easier to make an excuse for not writing tomorrow.

- You might just write better. That raw emotion you’re feeling will find its way into your prose, and might well give it power, lifting its quality above your previous best.

- Writing might give you fresh perspective on the cause of your mood. Writing may calm you down. Perhaps the massive problems your characters face will make yours seem less by comparison. As you push your heroic, fictional character to save the world while subduing monstrous evil, the hero you create might just create a hero inside you, a real person who can resolve the problem of the day.

Of course, there will be days when life legitimately prevents you from writing. Sometimes that event that soured your mood requires you to take action. You have to act, to deal with the problem. Writing is important, you know, but it’s a lower priority today.

I get that. But note a key difference. If you must act, do so. If you have nothing to do but sit and stew, then write instead. In other words, legitimate high-priority tasks can be an excuse for not writing, but a bad mood shouldn’t be.

Thanks to Jocelyn K. Glei, since her post with her interview of Seth Grogan about his contribution to the book Manage Your Day-to-Day inspired my own post.

How about that? I’ve just increased your writing time. Now you can write even when you’re in a rotten mood, as does—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Note: there’s a week left in the amazing Smashwords 1/2 price sale, where you can get 14 of my books for half price. Remember, they’re listed there at the full price, but when you click on any one of them, Smashwords gives you a code to use at checkout to get the discount.

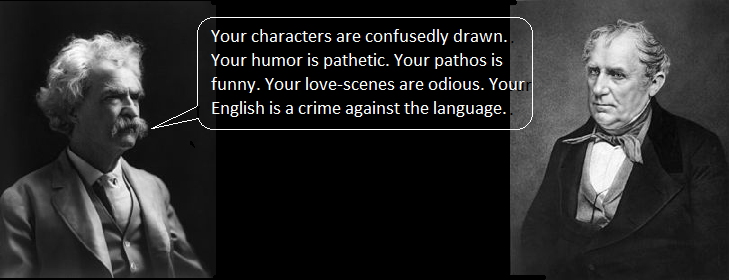

In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.

In Twain’s acerbic style, he starts by accusing three Cooper-praising reviewers of never having read the books. He then lays into Cooper, saying, “…in the restricted space of two-thirds of a page, Cooper has scored 114 offenses against literary art out of a possible 115. It breaks the record.” Twain asserts there are 19 or 22 rules “governing literary art in domain of romantic fiction” and says Cooper violated 18 of them. He lists those 18 rules.

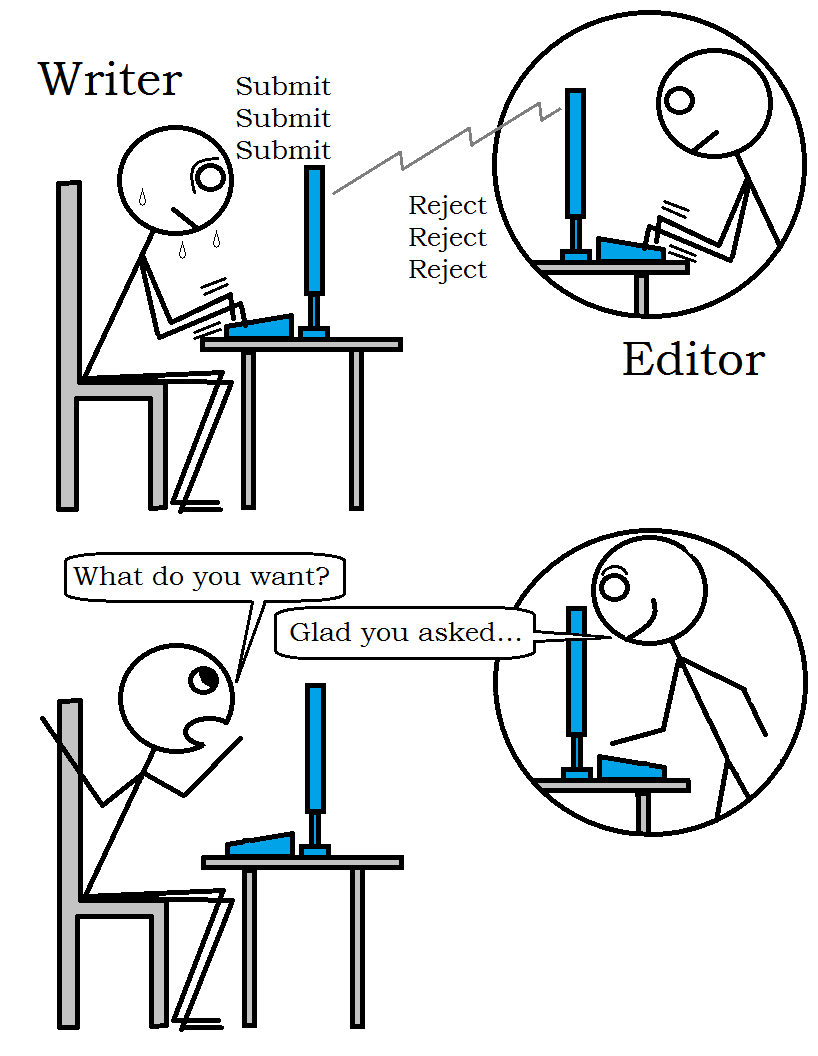

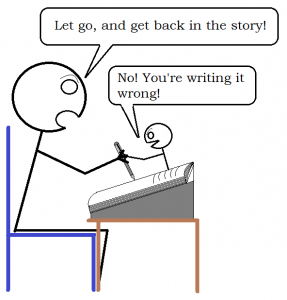

Today I’ll consider the topic of characters getting too big for their britches, and assuming a bigger (or different) role than the one planned for them. When this happens in your writing, should you take it as a good thing or a bad thing?

Today I’ll consider the topic of characters getting too big for their britches, and assuming a bigger (or different) role than the one planned for them. When this happens in your writing, should you take it as a good thing or a bad thing?