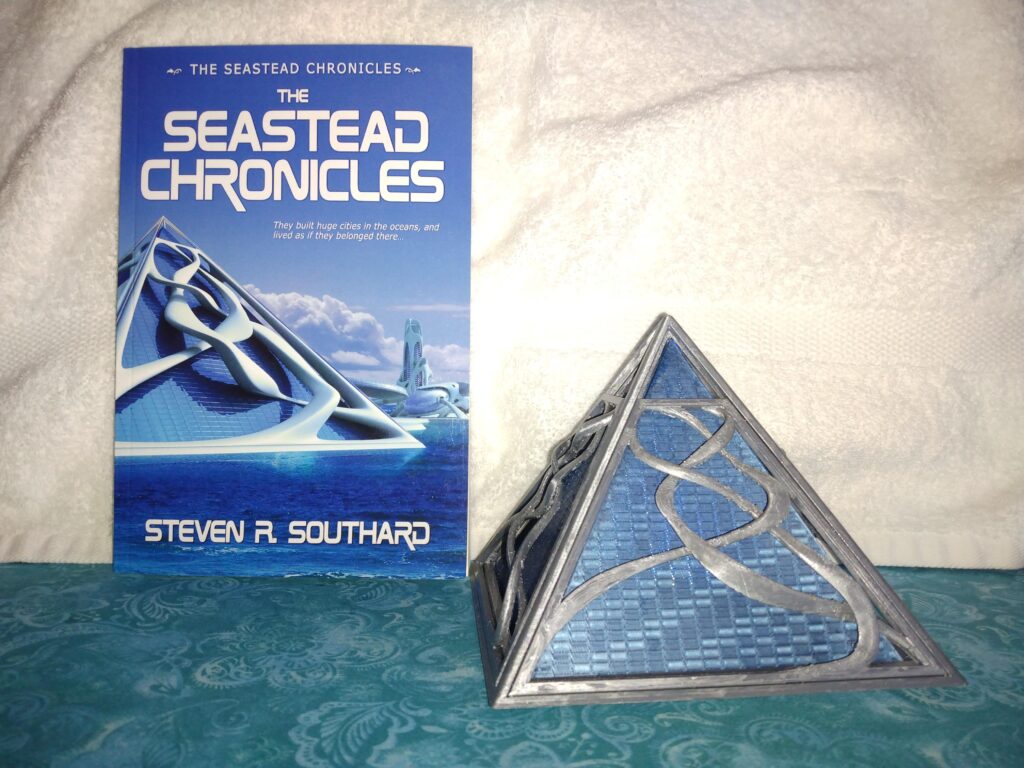

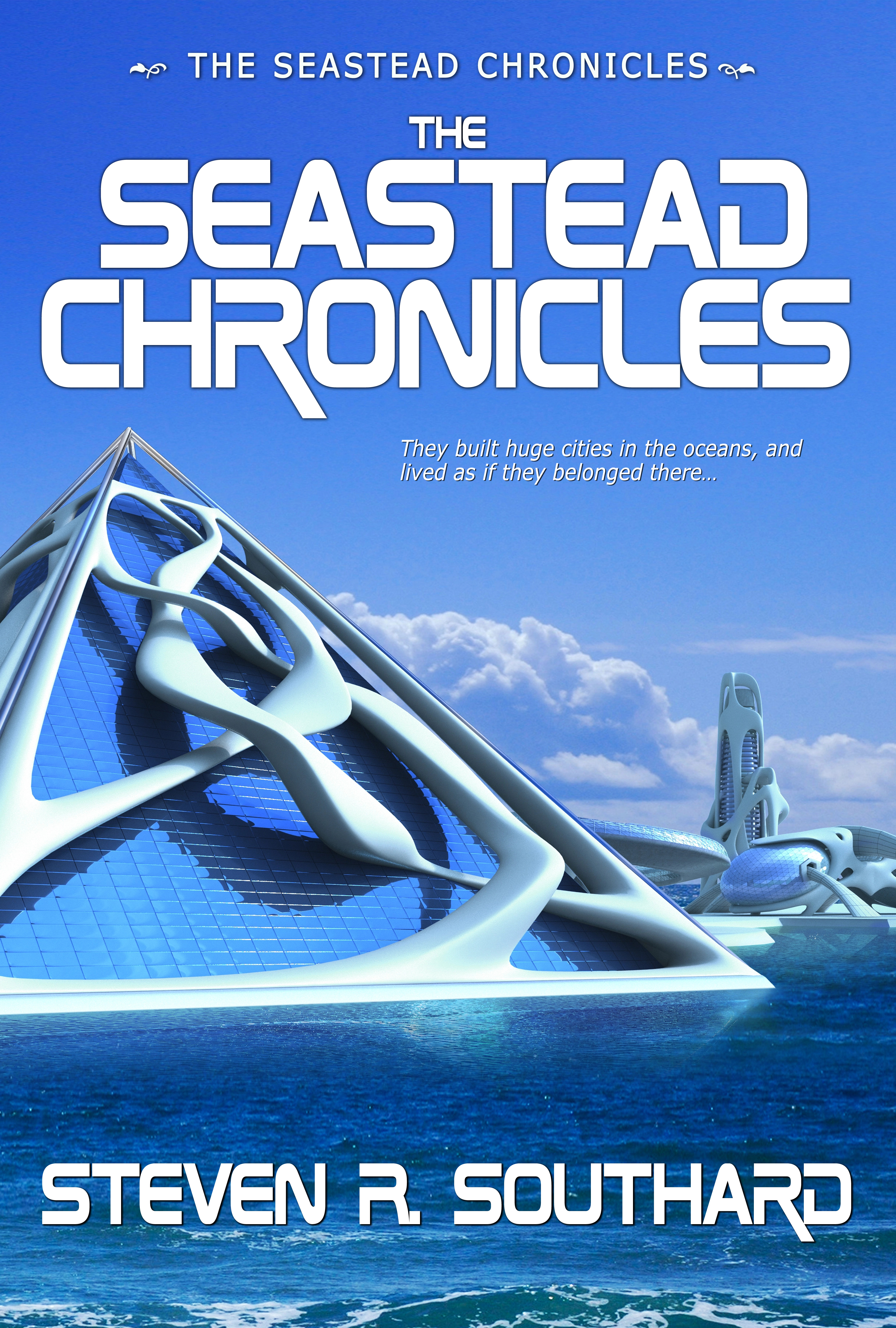

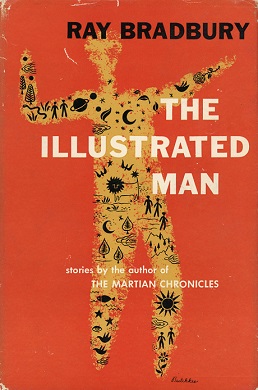

Seventy-five years ago, Doubleday published Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles (TMC). One month ago, Pole to Pole Publishing released my book, The Seastead Chronicles (TSC). A comparison of similarities and differences follow.

Similarities

Both books (1) contain the word “Chronicles” in their titles, (2) concern colonization, (3) belong in the science fiction genre, and (4) could be classified as fix-ups. I’m hard pressed to think of more similarities. On to the differences.

Creative Intent

Bradbury wrote all the short stories for TMC separately, with no intent of combining them. A publisher suggested the Chronicles idea to him. Bradbury then revised the stories to fit better, and added bridging narratives to form a consistent overall story.

I wrote a seastead short story with no initial plan to write more. After that, my muse suggested other stories and the notion of combining them took over. For that reason, TSC stories required no revision, and no bridging material to get them to mesh. Rather than calling it a fix-up novel, you could call TSC a “short story cycle.”

Plot Structure

Bradbury ordered his stories in a logical sequence and divided them into three sections, each occurring over specific designated years. Stories in the first part concerned exploration and initial contact with Martians, the second part with colonization and war, and the third part with the aftermath of what’s happened to humans on Earth and to Martians on Mars.

Although stories in The Seastead Chronicles appear in sequential order, I didn’t group them into parts, nor mention any specific years. The early stories depict initial seasteads and the search for seabed resources. The middle stories show the spread of aquastates and war between them as colonization proceeds. Later stories portray the blossoming of a new, oceanic culture.

Themes

Any discussion of story themes becomes subjective, since readers interpret tales in individual ways. Bradbury explored many deep themes in TMC, but overall I believe he intended a comparison of the colonization of Mars to the 19th Century conquest of indigenous people in the American West. The stories promote living in harmony with nature and suggest that those who don’t do so end up destroying nature and themselves.

For TSC, readers can draw their own conclusions. However, I intended to focus on humanity’s creative impulses, rather than its destructive ones. Though moving to a new environment introduces dangers, it also promotes new ways of thinking. From those, new cultures can arise, including fresh art, music, language, and religious beliefs. If you’re looking for real-life parallels, consider that all historical colonization efforts have changed the colonizers as they adapted to their new home.

Style

Bradbury wrote in a poetic, lyrical style, rich in imagery and metaphor. You can tell he loved the sound and rhythm of words. Few science fiction authors of his time wrote that way, so his prose stands out. By contrast, I’d characterize mine as plain and unadorned. I strive to make my sentences descriptive and easy to read.

Influences

The Wikipedia article on TMC lists several people whose works inspired Bradbury, including Edgar Rice Burroughs, Sherwood Anderson, and John Steinbeck. Editor Walter Bradbury (no relation) at Doubleday gave him the idea of combining his Martian-themed short stories into a single book.

For TSC, my influences start with Andrew Gudgel, who heard about seasteads and mentioned them to me. As general science fiction influences, I’d cite Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Arthur C. Clarke, and Ray Bradbury.

Final Thoughts

In this brief blogpost, I’ve missed some similarities and differences. To perform your own comparison, you’ll have to read both books and decide for yourself. Don’t take the word of—

Poseidon’s Scribe