How often do you read a book, watch a TV show, or see a movie, and think, “How clever! I wish I could come up with ideas like that.” You can. I’ll tell you how.

Seeing the World a New Way

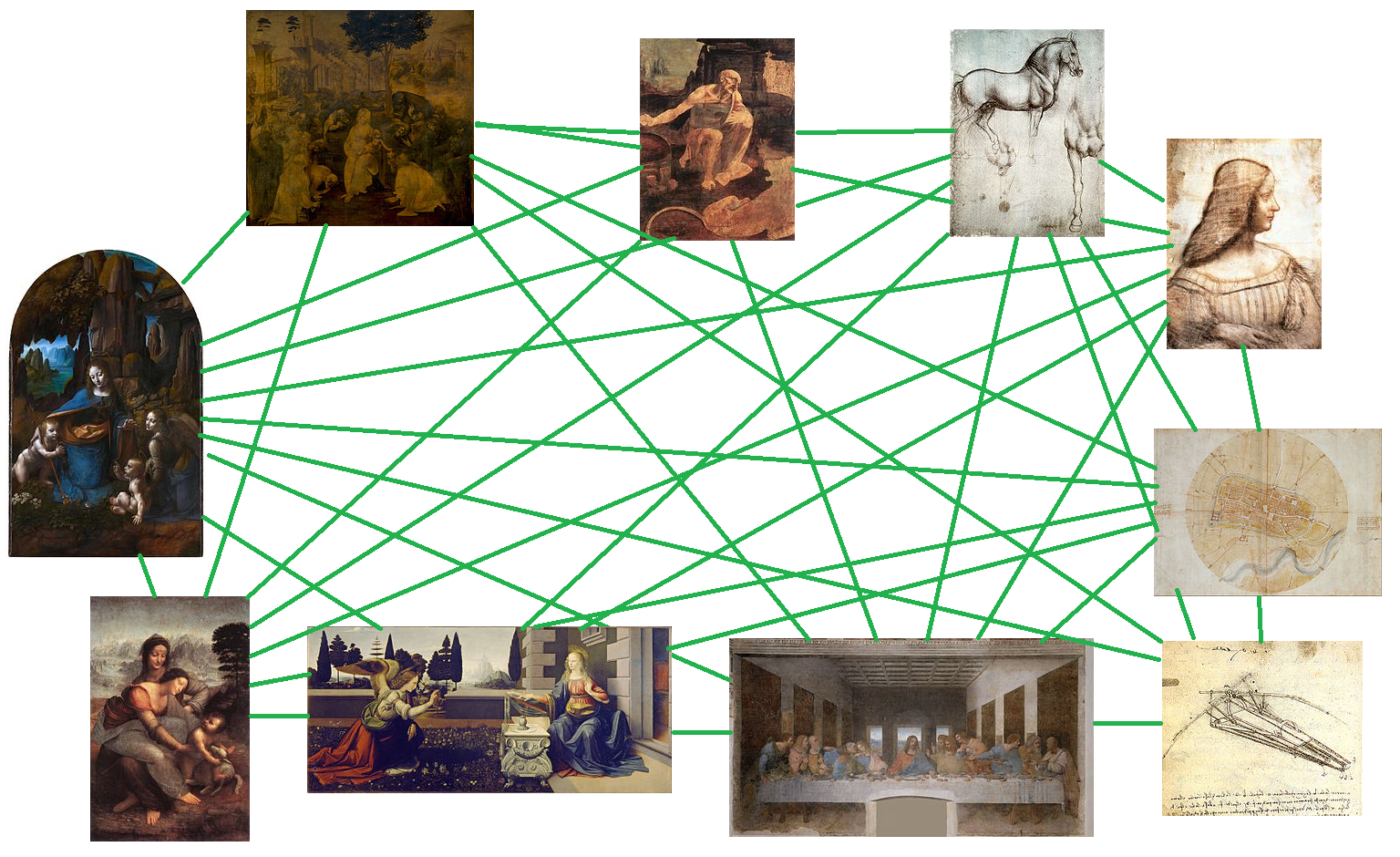

Creative people share a trait. Their brain neurons connect in a different manner than those of other people. When you sense the world around you, it is what it is. Creative people sense what the world could be.

Psychologists talk of ‘trait theory’ and the ‘Big Five’ personality traits. (For information, those are: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.) Of those, creatives seem loaded with an excess of Openness to Experience.

In this post, Luke Smillie and Anna Antinori explain how we all form mental models of the world. The closer our mental model matches the real world, the better we can deal with things.

Creatives play with their mental models. They think about unusual connections between unlike things. They imagine different possible worlds. They see in a way most don’t.

Binocular Rivalry

As one example, psychologists showed a group of test subjects a different image to their right and left eyes. The subjects tried to make sense of what they saw as one image rivaled the other.

The test revealed the more creative test subjects ended up ‘seeing’ a combined picture, one sharing attributes of both images to a greater extent than less creative subjects did.

Inattentional Blindness

In another test, psychologists gave test subjects a task requiring focus. They showed the subjects a video of six young people passing two basketballs around. The task—count the number of times people wearing white pass the ball.

Half of the test subjects concentrated so much on the task that they missed a bizarre event occurring in plain sight during the video. Those with more ‘openness to experience’ saw the event. Creatives saw what others screened out.

The Openness of Writers

The best fiction writers see what the rest of us see, but combine unlike things. Micheal Crichton merged his children’s interest in dinosaurs, then-current genetic engineering research, and mathematical chaos theory when writing Jurassic Park.

Suzanne Collins had been flipping TV channels between a reality show and coverage of a war when she combined the ideas and wrote The Hunger Games.

The ideas lie out there waiting for all of us, but fiction writers join and twist things and ask ‘what if…?’

Opening Your Mind

Can you train yourself to think like that, to see the story ideas others miss? I think so. In fact, I believe we’re born with the ability, and most of us lose it over time.

Most five-year-old children teem with creative ideas. They see animals in clouds, monsters under the bed, imaginative uses for sticks and stones and acorns. For some, that ability never fades, but most grow out of it, abandoning their magic dragons.

By increasing your creativity, you’re not learning a new skill, you’re re-learning a forsaken one.

Travel, especially foreign travel, can expose you to different ways of thinking that might spark creative ideas.

I like another technique, one much cheaper than flying overseas. Psychologists call it the ‘divergent thinking task’ but I call it ‘brainstorming twenty ideas.’ Take a common object and write down twenty alternative uses for it. Your ideas need not make practical sense, but don’t stop until you reach twenty. You can do this for any problem you face, not just imagining uses for things. By churning through the absurd and crazy ideas, you might hit on a brilliant one you wouldn’t have considered otherwise.

But That’s Not All

Disclaimer—writing a book requires more than just creativity. If you’re able to bolster your imaginative ability, you’ll generate good story ideas. But you still have to buckle down and write the novel or TV/movie script. Many writers consider that the hard part. Still, if the techniques in this blogpost help you over the first hurdle, that’s a win for you and for—

Poseidon’s Scribe

No, you protest. Those aren’t new. They’re just rehashes or remakes of old ideas, with some new flair added. They’re just old stories brought into modern times, well-used story lines put in a new setting, or known plotlines with the main characters’ genders reversed.

No, you protest. Those aren’t new. They’re just rehashes or remakes of old ideas, with some new flair added. They’re just old stories brought into modern times, well-used story lines put in a new setting, or known plotlines with the main characters’ genders reversed.