Want to know what science fiction will get published in 2026? You’ve come to the right place, at the right time.

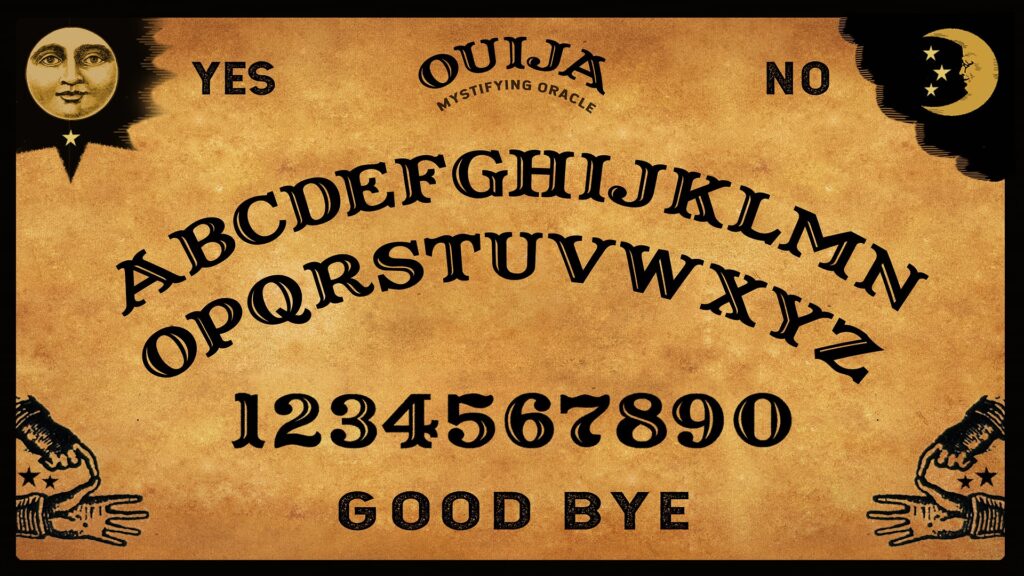

I’ve made scifi publication predictions before, with little success. However, the methods I used—crystal balls, tea leaves, tarot cards, astrology, palmistry, ChatGPT, and a Ouija Board—didn’t produce accurate prophesies.

This year, I sought the most reliable and proven prognostication technique of all—the method of Nostradamus himself.

Imitating that 16th Century French seer, I secreted myself in the attic, meditated, prayed, consulted astrological charts, and made sketches and notes of the visions that came to me. To my surprise, a set of four-line poems—quatrains—emerged from this process. Contrasting with those of Nostradamus, my quatrains came to me in English.

I’ll provide the quatrains, and my interpretation of their cryptic phrasing, below.

Translated SF

In ’26 the science fiction bands

Will stretch to languages of distant lungs

The tales from writers writ in other lands

Will translate fiction from their foreign tongues

I believe this means we’ll see a surge of translated science fiction in 2026.

Space Opera

The coming year will see space opera bloom

Vast empires ’cross the galaxies galore

Equipped with FTL, the starships zoom

Through epic dramas, aliens, and war

This suggests a revival of space opera in 2026. FTL = faster than light.

Characters Beyond Gender

Some authors will play more with gender norms

Not always stuck with females and with males

Their characters will switch or take new forms

Within new trans and gender-fluid tales

I interpret this to mean we should expect to leave female and male characters behind, in favor of new genders, changeable genders, non-genders, and who knows what else.

Serial Fiction

We’ll see rebirth of serials again

With shorter bites to match attention spans

Subscriptions, author newsletters, and then

Some dedicated apps with bundled plans

If I’m construing the meaning of this in the right way, we should find authors writing short chunks with cliffhanger endings to entice readers to subscribe to read the complete stories in serial form.

Hybrid Genres

Next, hybrid genres will remain a trend

Scifi can mix with others all the time

To form a very complement’ry blend

With horror, and romance, and even crime

This quatrain hints at the continuing trend of mixing scifi with other genres.

Year of the Horse

In Chinese myth, this next year marks the horse

And scifi books will emulate the steed

With high adventure, optimistic force

Heroic, active, with pulse-pounding speed

It’s hard to extract much meaning from this. Perhaps it’s suggesting scifi in 2026 will take on equine attributes of power, independence, perseverance, and confidence.

Conclusion

Look for the results of these predictions next December. Being curious, I couldn’t resist applying Nostradamus’ methods to discover what the new year will mean for me. Here’s what resulted:

This lies beyond the sight of any seer

Will he soon join “best-selling author” tribe?

He’ll work hard but the outcome is unclear

It’s unknown what awaits—

Poseidon’s Scribe