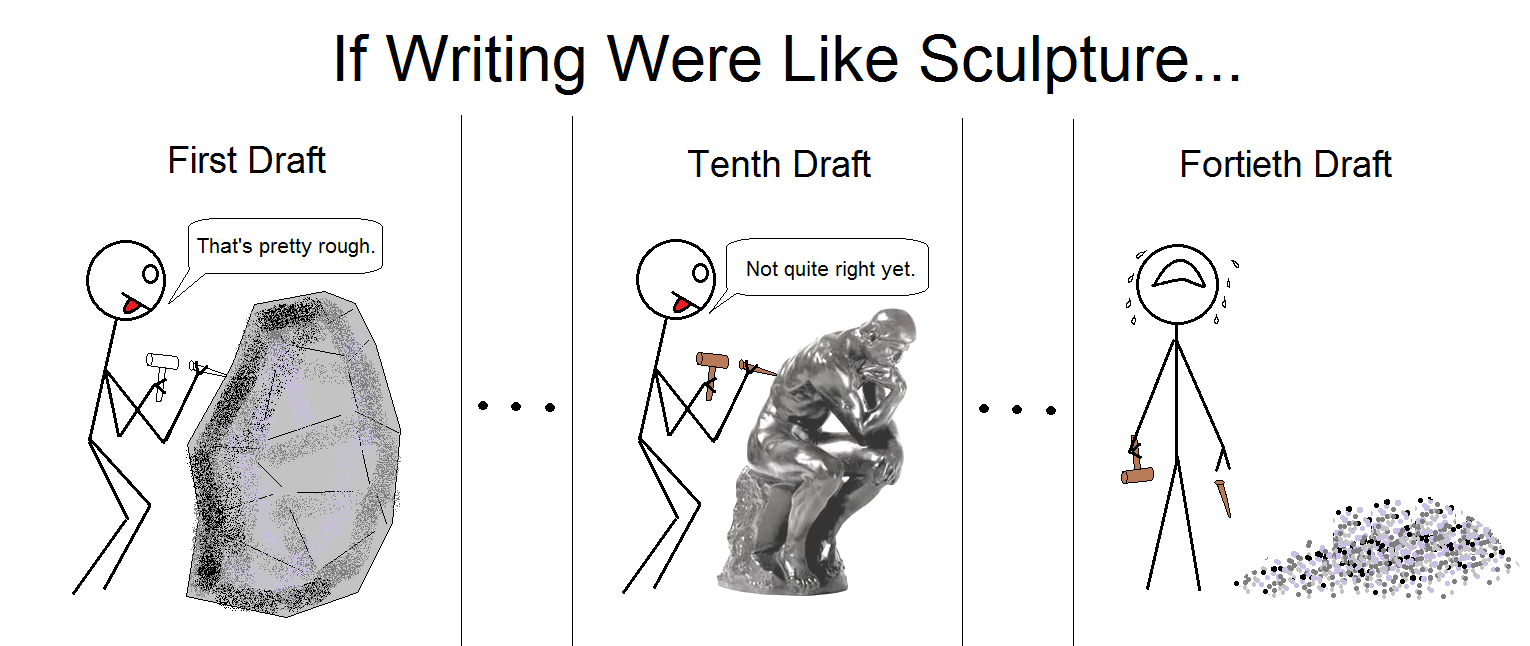

On one hand, you’re anxious to send your story to an editor and see it published after its many revisions. On the other hand, you’re not sure it’s quite ready yet.

How do you know when you’ve truly finished a story?

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’

- Robert Heinlein: “They didn’t want it good; they wanted it Wednesday.”

- Laura Lippman: “You have to be able to finish. The world is full of beautiful beginners.”

- Michael Crichton: “Books aren’t written—they’re rewritten. Including your own. It is one of the hardest things to accept, especially after the seventh rewrite hasn’t quite done it.”

- Isaac Asimov (paraphrased from my memory): I write a first draft and never change a word. If they want a five-thousand-word story, I type five thousand words and stop. With any luck, I’m at the end of a sentence.

Thanks, Famous Writers! Great quotes, but not particularly helpful. Next I turned to the blogosphere and came up with some useful posts on the topic by Chris Robley, Dr. Randy Ingermanson, Bryan Hutchinson, Jessica Clausen, and James Duncan. I recommend you peruse those posts at your leisure for more in-depth advice.

Here’s my distillation of guidance from those blog posts, mixed with my own experience. It boils down to your attitude toward the story:

- Are you proud of the story? Are you proud enough of it that you’d be happy to see it in print, with your name as the author? If so, it may be ready, so long as it’s not a false pride, and instead stems from the confidence that you’ve done all you can to make the story good.

- Are you tired of, or even sick of, working on the story? Your creative muse is aching to move on to something else, and the thought of spending more time on this story is depressing. If this is truly a reaction to working on the story, not the story itself, it may be ready. If you’re sick of the story itself because you think it’s terrible, or you can no longer summon up the enthusiasm you once had for it, it probably still needs work. In that case, it may be best to set it aside for a few weeks or months so you can look at it fresh later.

At some point, you need to decide: (1) submit the story for publication, (2) shelve it for a while and edit it later, or (3) abandon it. Sometimes circumstances will force your decision—things such as an editor’s deadline, the desire for publication, the fickle muse’s yearning for a different writing project, etc.

Sometimes, there’s nothing forcing you to decide and you’re still stuck in limbo, wondering if the story is ready. At that point, you might want to ask yourself whether it’s the story’s readiness that’s in question, or yours. Has the story become a sort of child, one you’re trying to protect from the harsh world out there?

If so, remember: you’re a writer, and writers create stories for readers to enjoy. Time to let that story out, and let it find whatever acclaim or obscurity it will, while you move on to write the next one. You can do this; take it from—

Poseidon’s Scribe