It’s easy for your favorite authors to intimidate you. When you grow up enjoying reading, and when you study fiction by the world’s best writers in school, it’s natural to put them on a pedestal. They are geniuses, titans, specially gifted demigods with an ability beyond your understanding.

At some point, you might be tempted to try writing fiction yourself. Immediately you reject the notion out of hand. In your mind, you compare yourself to those great authors and dismiss the idea of creating any fictional work. Impossible. Laughable. Pretentious. You’ll never write as well as they do.

I’ve mentioned this phenomenon before, but I’d like to explore the problem in greater depth.

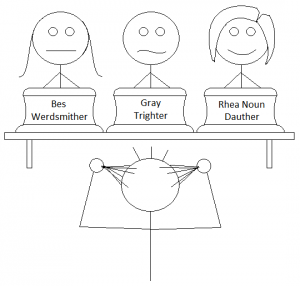

Just for fun, let’s give our intimidating scribblers some names. You have your own favorite, famous novelists in mind, but we’ll say that you idolize Bes Werdsmither, Gray Trighter, and Rhea Noun Dauther.

Okay, not the funniest puns, but they’ll do.

When I mentioned this issue in a previous blog post, I made two points:

- You can’t know today, before you begin writing, how you’ll eventually stack up against your imagined pantheon of Bes, Gray, and Rhea. Remember, all three of them started out as unknowns, too, like you are now.

- Even if you’re right, and you never end up writing as well as Bes, Gray, or Rhea, remember that there’s room in the world for lesser-known writers. You don’t have to aim for eternal fame or a mansion on your own island. You can still write your own stories, reach some readers, and make a little money.

Even though you worship Bes, Gray, and Rhea, I’d advise you not to try to imitate them, anyway. For one thing, why should readers read your copy-cat stories when they can purchase the real thing? Also, it’s best to allow your own inner voice to emerge, rather than attempt to channel some famed author.

Even though you worship Bes, Gray, and Rhea, I’d advise you not to try to imitate them, anyway. For one thing, why should readers read your copy-cat stories when they can purchase the real thing? Also, it’s best to allow your own inner voice to emerge, rather than attempt to channel some famed author.

Sure, you adore the characters, style, settings, and plots of Bes, Gray, and Rhea, but I suggest you strike out in a different, but related, direction. Write in their genre if your interests reside there, but make up your own characters, style, settings, and plots.

If you find some success as a writer someday, I assure you it won’t be because you copied someone else. It will be due to the separate and distinct course you charted, or the path your own muse led you along.

By the way, when your muse does whisper something outrageous (and she will), listen to her. She may implore you to write a story quite different from anything in the bibliographies of Bes, Gray, and Rhea. The muse might pull you in a strange and new direction you never imagined. Don’t ignore her. She’s your inner creativity, the voice of your soul calling you, so don’t hang up.

You can still enjoy novels by Bes, Gray, and Rhea, without dreaming of writing like those three. Your goal, one you should visualize, is to become the best author you can. It’s a process of continual improvement.

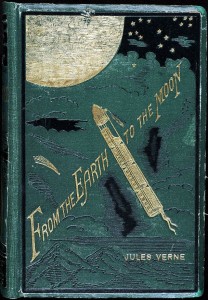

My personal geniuses, titans, and demigods are Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov, and Robert Heinlein. As readers of my blog know, my stories aren’t like theirs at all. I’ve taken off in a different direction, a unique course steered by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.

They claim this will be the first time a human-built spacecraft has landed on a comet.

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

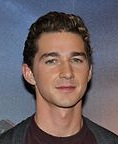

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense. The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

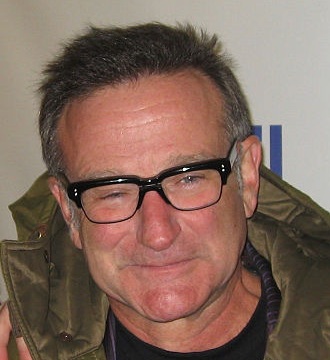

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility. Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “

Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “