Sometimes science fiction authors create religions for their stories. According to Wikipedia, they do this to satirize, to propose better belief systems, to criticize real religions, to speculate on alien religions, to serve as stand-ins for real religions, or other reasons.

Examples

I could cite many cases of this, but I’m most familiar with the following:

- Church of Science – Foundation (1951) by Isaac Asimov

- Church of All Worlds – Stranger in a Strange Land (1961) by Robert A. Heinlein. Note: This book inspired the creation of a real religion by the same name.

- Bokononism – Cat’s Cradle (1963) by Kurt Vonnegut

- Bene Gesserit – Dune (1965) by Frank Herbert

- Earthseed – Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents, (1998) by Octavia Butler

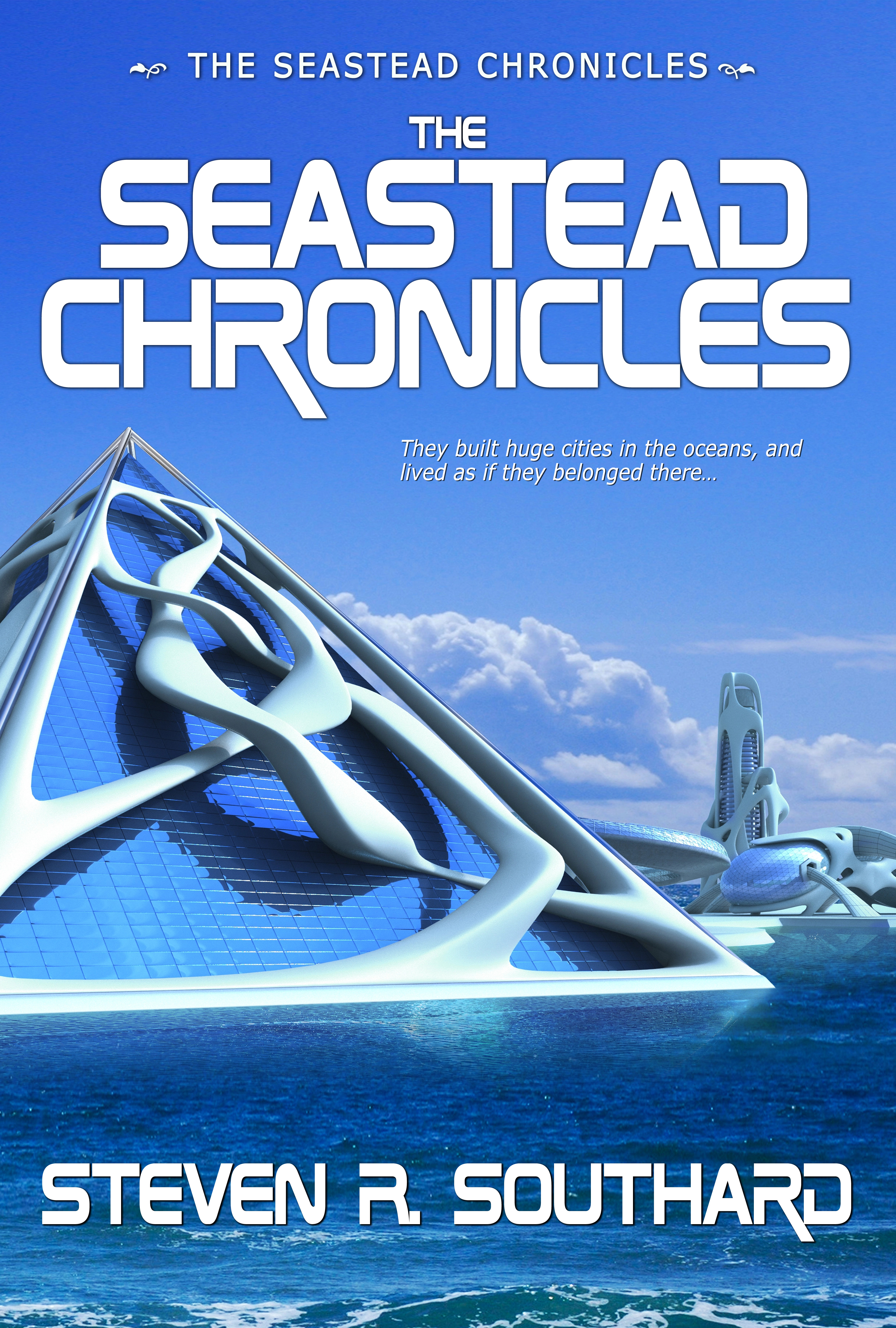

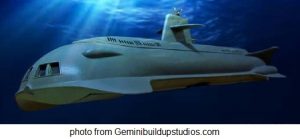

Oceanism

For my new book, The Seastead Chronicles, I created the religion of Oceanism. It begins with one man’s revelation and spreads through the seasteading community of aquastates. In some of the book’s stories, I mention certain aspects of Oceanism, but never describe it in full detail. Oceanism serves the purposes of the stories, not the other way around.

I don’t mean to make Oceanism sound like a fully-formed religion, complete in every aspect. Few writers, least of all me, would go to that much trouble. I created more features of it than appear in the stories, but not much more.

Aspects

All religions, even fictional ones, share certain basic attributes. Here’s how Oceanism addresses several of these aspects.

- Belief in a higher power—For Oceanists, that’s their god: Oceanus.

- Rules for living a virtuous life—Oceanists seek to obey the 5 Orders and avoid committing the 5 Sins

- Sacred Texts—Oceanists call theirs the Tide.

- Celebrations and Holidays—Oceanism recognizes five sacred days, evenly spaced through the year

- Prayer and Meditation—Oceanism advocates daily meditation, while mostly immersed in water.

- Rituals—Oceanists participate in the Five Life Events. Of these, Immersion is the most rigorous. During Immersion, adherents undergo permanent dying of their skin to some watery color, webbing of fingers and toes, inking of a forehead tattoo, and choosing an aqua-name.

- Symbols and Iconography—the five-armed starfish serves as the main symbol of Oceanism, but adherents may choose any sea creature for their forehead tattoo. The number five contains special significance for Oceanists.

- Sacred Spaces—Oceanism services take place in temples. There, worshippers wear bathing suits and sit in saltwater up to their necks.

- Leaders who provide guidance—a High Priest leads the religion, with five pentapriests supporting him, and a hierarchy of priests supporting them.

Purpose

Earlier I cited several reasons authors create fictional religions. Oceanism exists to illustrate one of the ways cultures form in new environments. I imagined, if people moved to the sea in large numbers, new sea-based cultures would also arise and catch on, with new artforms, music, jargon, and religious sects. My stories make no judgements about the validity of Oceanism or any other religion. I leave religious satire and criticism to others.

Given what I’ve said about this religion, would you join with Oceanists? If not, does it sound plausible, at least? Feel free to leave a comment for—

Poseidon’s Scribe