Inspired by K. M. Weiland’s wonderful post, “How Not to Be a Writer: 15 Signs You’re Doing It Wrong,” I decided to make my own list.

My list differs from hers, since it’s borne of my own experiences. Moreover, I’m sure there are plenty of unlisted items I’m still getting wrong, that hinder me from greater success.

My list differs from hers, since it’s borne of my own experiences. Moreover, I’m sure there are plenty of unlisted items I’m still getting wrong, that hinder me from greater success.

Arranged in rough order of the writing process, here are a baker’s dozen ways you’re writing wrongly:

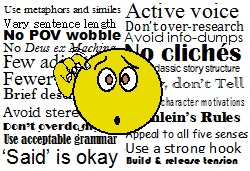

- You’re not actually fitting one word up against another. In other words, you’re not writing any fiction. Maybe you’re easily distracted, doing too much research, talking about being a writer while not writing, or just intimidated by the prospect. Doesn’t matter. If you’re not writing, you’re never going to be a writer.

- You bought your limousine and mansion before the advance arrived. Let’s set some realistic expectations here. Most likely, you’re going to labor in obscurity for a while, probably years. First time best-sellers are very rare. Heck, best-selling authors themselves are rare. Only a tiny percentage of writers support themselves with their writing.

- You’re copying someone else’s style. After all, (you’re thinking), if it’s working for James Patterson, J.K. Rowling, Nora Roberts, John Grisham, etc., then it should work for you. Inconvenient fact—readers already have a Patterson, Rowling, Roberts, Grisham, etc. Create your own style.

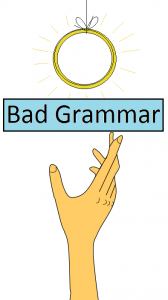

- You’re sure the rules don’t apply to you. I’m talking about those pesky rules of English and the rules of literature, stuff like spelling, grammar, and story structure. All those rules are for mere plebeians, not you, right? Actually, you’re really supposed to know them. As for always following each rule to the letter, see item 5 on my list.

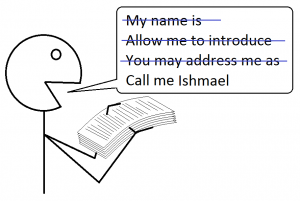

- You obsess about following the rules. You’re now a walking dictionary and could qualify to teach English at Harvard. You chiseled the rules onto granite tablets and now pray before the tablets twice daily. Why are your stories not selling? There’s an overarching rule you forgot—you’re supposed to write stories people want to read. If some rule of writing is keeping you from telling a great story, break the rule. Just don’t go too far (see item 4).

- You quit before “The End.” Around the world, desk drawers and computer file directories bulge with half-finished stories. If you would be a writer, you must finish your stories.

- Your epidermis is on the thin side. In other words, you don’t take criticism well. The most mundane comment from someone in your critique group or from an editor will either set you off in a bout of inconsolable sobbing or high-minded ranting at the imbeciles that surround you. Get a grip. They’re not attacking your personal character; they’re trying to help you improve your story.

- You inhabit a world that’s just too slow to recognize the wonder that is you. How frustrating that must be, to cast your gaze at the mortals about you and see them not bowing before the genius in their midst. Well, genius, here’s a word you might look up: patience. Recognition, if it’s to come at all, will come in time.

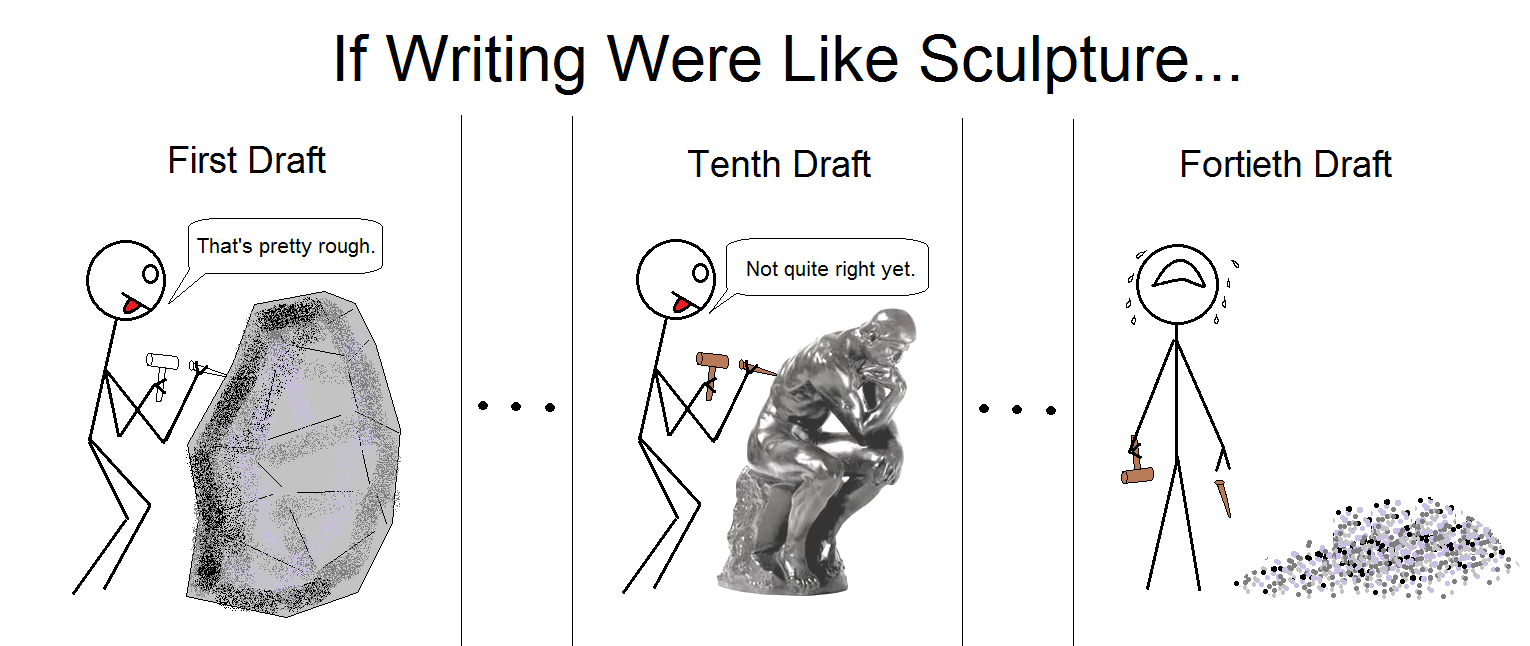

- You revise edit reword amend change adjust vary redraft alter rephrase modify wordsmith rewrite your story endlessly. Sure, that story will be perfect once you work on it a bit more, just add this and delete that, change the POV character, throw in some better verbs and adjectives. It seems like it’s never quite right. True, it never will be perfect, but it could be good enough.

- You defy Submission Guidelines. What’s with all these editors, anyway? Each one has a particular format for story submissions, and each format is different. That’s too much trouble for a great writer like you. Your story is so superb the editor will overlook how you flouted a few guidelines, right? Nope, wrong again. Obey those guidelines.

- You never click ‘Submit’ or ‘Send.’ That’s because if you do, some editor might actually see your precious story, might read it, and might not like it. Better to keep your story safe with you, in your home, where nobody can ever criticize it. Uh…no. Show your baby to the world. It will be okay.

- Rejections are reasons to revise edit reword…rewrite your story. An editor has rejected your story, perhaps even explained why. To you, that’s a sign you must rewrite it before it can be good enough to submit elsewhere. No. Go ahead and submit it elsewhere immediately. (However, if an editor rejects your story but says she’ll accept it if you revise it in a particular way—ah, that’s the sign that you should rewrite and submit it to her again.)

- You’re relaxing after submitting a story. There, you just sent your story on its way. Now you can kick back and wait for the acceptance, the contract with the six-figure advance, the launch party, the book tour, and the TV interviews. Sorry, no. You’re supposed to be a writer. Start writing your next story already.

Avoid those pitfalls and you’ll be on your way to becoming a published writer. Best wishes in all your writing efforts, from—

Poseidon’s Scribe

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’

We could seek advice from accomplished authors. Unfortunately, the various quotes I’ve compiled run the gamut from the ‘don’t edit at all’ extreme to ‘seven revisions might not be enough.’