Today Poseidon’s Scribe introduces a new occasional feature to this blog. I had the opportunity to interview author Anne H. Petzer. She’s a South African, now living in Prague.

Today Poseidon’s Scribe introduces a new occasional feature to this blog. I had the opportunity to interview author Anne H. Petzer. She’s a South African, now living in Prague.

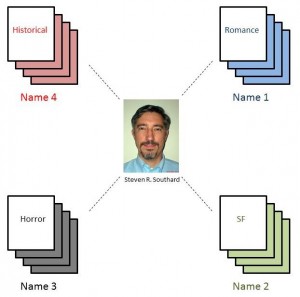

Anne is the author of several stories in a series about an operative with Feline Intelligence – Czech Republic. Oh, yeah, the operative is a cat named Zvonek. Anne has also written Snow Cat based on Czech legend.

Here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: When and why did you begin writing?

Anne H. Petzer: I started writing way back in Primary school. I can still remember my first poem I wrote; I must have been about 10. It was a poem called ‘Dad’ and it was for my father for Father’s Day. When I was going through his things after his death, I was then 33; I found it and other poems of mine he had kept in among his papers.

As to why, guess I have always felt the need to write as a way for expressing myself.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

Anne: The easiest is the sorting out the story in my head and then I usually write a rough plan of it to follow when I am writing it. Not the details mind, just the main events that I want to happen to create the story as a sort of guide for me to follow. I have to say though the end product of my story often is completely different to when I start. The Miracle of the Carp is an example of that. I honestly didn’t know how I was going to present it. All I knew was that I wanted to do a story about the carp.

The hardest is choosing the names and descriptions of my characters, feline or human. It may sound silly but I agonise over names of characters for each story. The name of the boss feline in the Zvonek series came about after an evening of debating with friends and a friend of mine actually named her. The names have to feel right.

P.S.: What inspired you to write the Zvonek 08 series?

Anne: Zvonek is my tom cat of seven years. When he was just over a year old he was knocked down by a car and left the whole night on a pavement a little way from my home. The next morning he was found by a kind person and taken to a cat shelter where he was cared for. He was an outdoor cat at this stage as the area where I lived had gardens and I therefore thought he would be protected. After much searching we found him and I brought him home still very frail. It took him a good three months to recover and it was during that time that series was created. Zvonek is now an indoor cat and goes for walks with me on a lead.

P.S.: Please describe the world of your Zvonek 08 stories.

Anne: Zvonek works as a spy in Prague connected to Feline Intelligence, which is an organisation that operates throughout the EU. His cover is being a pet to a kindly human known as his Mom. But that is where the human contact stops. His mission is the safety of cats from domestic and international foes. Their domestic arch enemies are the rats who constantly battle for dominion of the streets of Prague 10. His international enemy is a beautiful Siberian queen for whom he a thing until she revealed her true self nearly causing his downfall. The stories include Czech culture and legends as a background to work on.

P.S.: How did you come to write Snow Cat?

Anne: Krkonoše is a mountain range in the Czech Republic I have visited often, but only during winter. I wanted to write a book of stories surrounding the iconic areas of the Czech Republic and Snow Cat was originally part of that series. It was inspired by the storm cat in the story The Mousehole Cat by Antonia Barber.

P.S.: What is the audience you’re trying to reach in your stories?

Anne: I would say anyone young in age and heart who loves cats and fantasy with a bit of fun.

P.S: What are your current writing projects?

Anne: I am working on book four of the current series of Zvonek 08 and collecting ideas to put together a collection of stories surrounding iconic areas of the Czech Republic.

P.S.: What advice can you offer to aspiring writers?

Anne: Believe in your work, co-operate with your publisher and never stop writing.

Thanks, Anne. Inspiring advice, and her books sound fascinating and fun! You can find out more about author Anne H. Petzer at her website, her blog, the Facebook site for Zvonek 08, or the Twitter site for Zvonek 08. Her site at Gypsy Shadow Publishing is here.

Poseidon’s Scribe