When George Villiers, the 2nd Duke of Buckingham wrote those words for his play “The Rehearsal” in 1663, I believe he had today’s blog post in mind. For, ay, I intend to discuss how to plot a story.

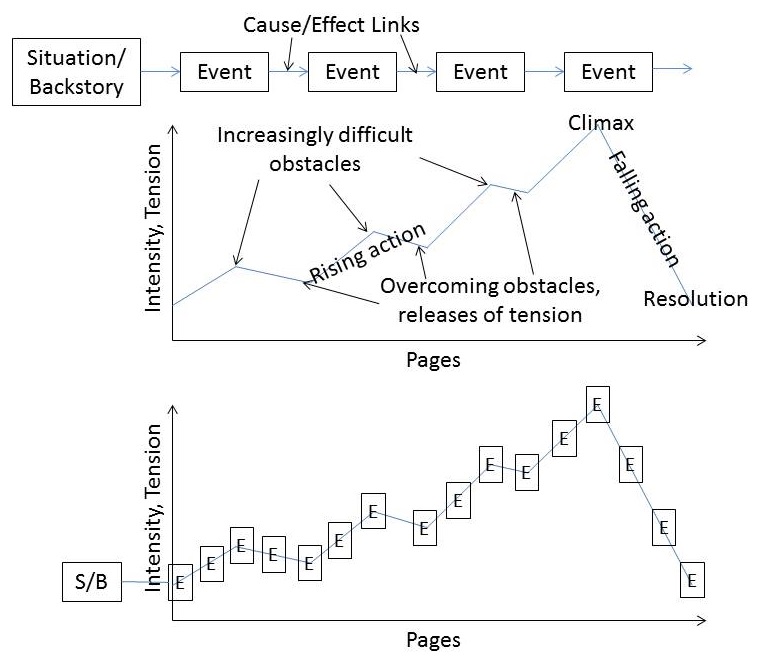

First, what is a plot? It is simply a series of connected fictional events. Here are two rules about these events:

1. In a non-humorous story, the connections between events should be logical, with a minimum of lucky coincidences; the events should be related by cause and effect.

2. To make your story appealing to readers, there should be a certain structure to these events. That is, experience has shown this particular plot structure (sometimes called a “dramatic arc”) to have a maximum emotional impact.

But how are rules 1 and 2 related? What does it mean to have a cause-and-effect chain of events that rises and falls? Think of it this way. Your story must have a protagonist with a problem, a conflict of some kind. Often there is both an external and internal conflict.

I’ve said before that stories are about the human condition. More specifically, stories show human ways of dealing with problems. It may seem strange to generalize that way, but without a problem or conflict, you have no story. Even if there are no humans in your tale, your non-human characters are really just standing in for people.

Back to plotting. Think of the series of events (Rule 1) as events showing your protagonist encountering an initial obstacle, overcoming it, then encountering a worse one, overcoming that one, etc. Each obstacle thrown at her causes her to struggle against it. Her struggle causes the antagonist (which may be a person or nature or anything) to oppose her even more. That’s what Villiers described as a plot thickening.

Back to plotting. Think of the series of events (Rule 1) as events showing your protagonist encountering an initial obstacle, overcoming it, then encountering a worse one, overcoming that one, etc. Each obstacle thrown at her causes her to struggle against it. Her struggle causes the antagonist (which may be a person or nature or anything) to oppose her even more. That’s what Villiers described as a plot thickening.

Think of the dramatic arc (Rule 2) as a portrayal of the increasing difficulties for your protagonist as she contends with her problems. Tensions should increase in this section, culminating in a climactic turning point. There she must confront both her external and internal problems. The remaining events convey the resolution of the conflict and represent a decrease in tension.

Although I’ve geared this discussion to short stories, all fiction is similar. Screenwriter H. R. D’Costa has written a wonderful blog post providing the secrets of movie plot structures.

Oh, one more thing about problems and resolutions—if you have a problem with what I’ve said in this blog post, leave a comment and I’ll try to resolve it. I also accept praise by the heapful. I’ll close by saying, Ay, now the plot’s been thickened by—

Poseidon’s Scribe