You were wondering about this new story of mine, “Time’s Deformèd Hand,” so I’ve written this blog post to answer all your questions. It’s the least I can do to satisfy your curiosity. Luckily for both of us, the post contains no spoilers.

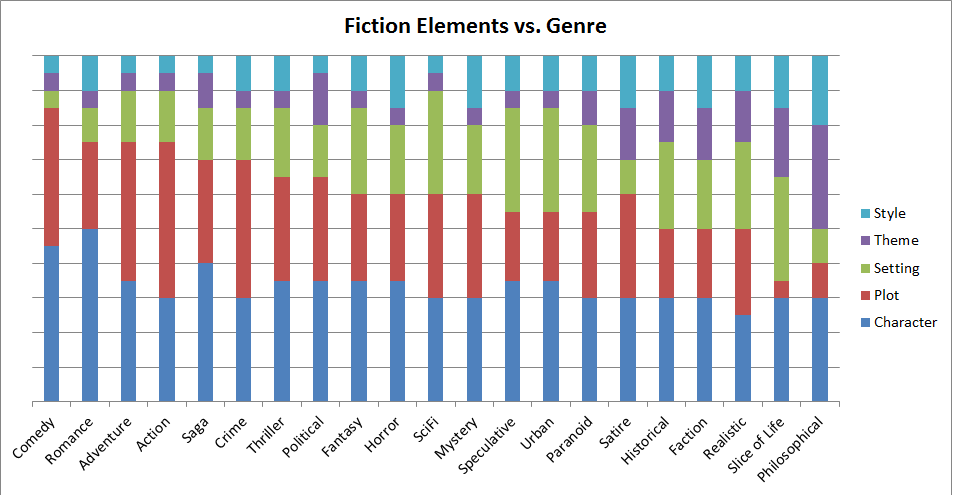

A: Here’s a short book blurb: “Time for zany mix-ups in a clock-obsessed village. Long-separated twins, giant automatons, and Shakespeare add to the madcap comedy. Read it before it’s too late!”

Q: What’s with the weird title, and why is there a grave accent mark in the word ‘deformed?’

A: The title is stolen from Shakespeare’s “The Comedy of Errors.” In fact, I pretty much ripped off the Bard’s whole play. The story has many, many references to time, clocks, and calendars, and all the sorts of errors associated with time measurement, so the title is appropriate. The grave accent mark (`) means to pronounce that usually-silent ‘e’ as you would in ‘scented,’ to make the poetic rhythm come out right.

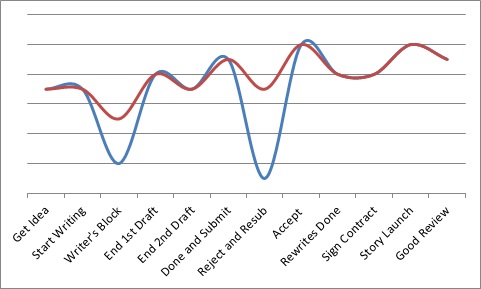

Q: What made you think of writing it?

A: I got the idea, somehow, to combine Shakespeare and clockpunk. I wanted the tale to be lighthearted, so I picked one of Shakespeare’s comedies. Having raised a set of identical twins myself, I was drawn to “The Comedy of Errors” due to all its mistaken-identity gags. Rather than two sets of identical twins separated at birth, I thought I’d have just one set, but each young man has a clockman, and all clockmen are identical.

Q: What are clockmen?

A: In my story, clockmen are clockwork automatons, invented by Leonardo da Vinci a century before my story. They’re eight feet tall, with an outer shell of wood covering the metal gears, ratchets, and cogs. They display a clock on their chest, and have a large, wind-up key protruding from their back. Due to a special property of a certain kind of wood, clockmen are sentient, though they seem dull-witted.

Q: What are the story’s strangest characters?

A: First, I’d have to say the town’s Wachmeister, or constable. Wachmeister Baumann is pompous, and also overconfident, considering he can’t seem to correctly pronounce any policing terms. Then there’s the proprietor of the city’s clockman repair shop, a certain William Shakespeare. Herr Shakespeare had moved from England to this Swiss village. For a repairman, he has the rather odd habit of speaking in iambic pentameter, and a deep understanding of human nature.

Q: What do you mean by ‘many references to time?’

A: The setting of the story is a Swiss village called Spätbourg (“late-town”). It is shaped like a clock, with twelve streets radiating out from the center. It contains the Tempus Fugit Restaurant, the Oaken Cuckoo Tavern, and the Sundial Inn. In addition, the story includes several clock jokes, clock mix-ups, as well as clock and calendar paradoxes.

Q: When and where can I buy it?

A: Thought you’d never ask. The book is launching today! You can buy it here, here, and here, and soon it will be available at Gypsy Shadow Publishing and other places.

What? You have more questions about “Time’s Deformèd Hand?” Better leave a comment for—

Poseidon’s Scribe