Welcome back, fellow literary adventurers. We’re traveling Around the World in Eighty Days, 150 years after the publication of Jules Verne’s famous novel. Today, we’re in Chicago, but it wasn’t exactly a breeze to get to the Windy City. Well, in a way it was…

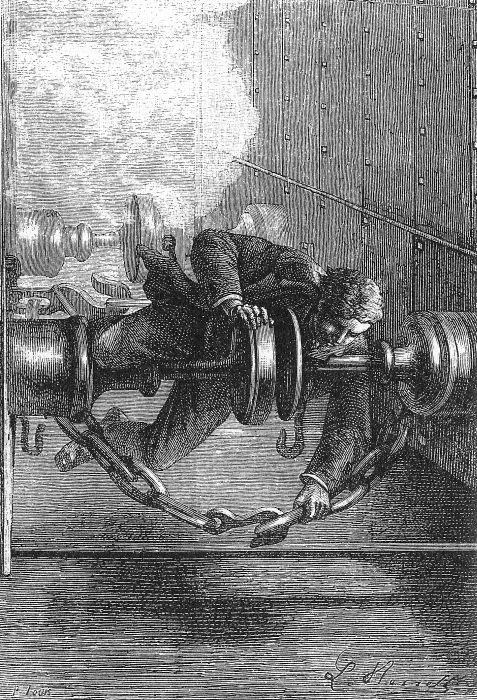

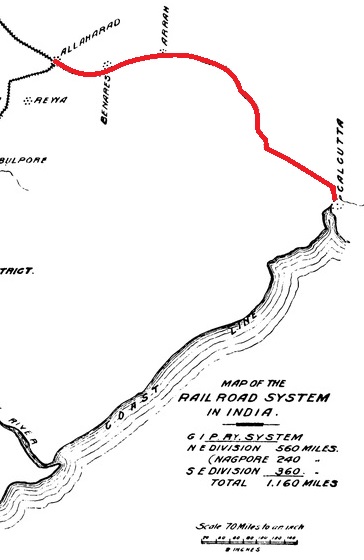

We left Princess Aouda and Detective Fix at the Fort Kearney station in Nebraska, waiting the return of Phileas Fogg. He’d left with thirty soldiers to rescue Passepartout from the Sioux. At dawn on the 9th, Fogg returned, having rescued his servant and the other missing passengers. However, he’d have to wait until that evening for the next train. Fix made arrangements with a man named Mr. Mudge to ride a sail-powered sledge over hard-packed snow from Fort Kearney to Omaha.

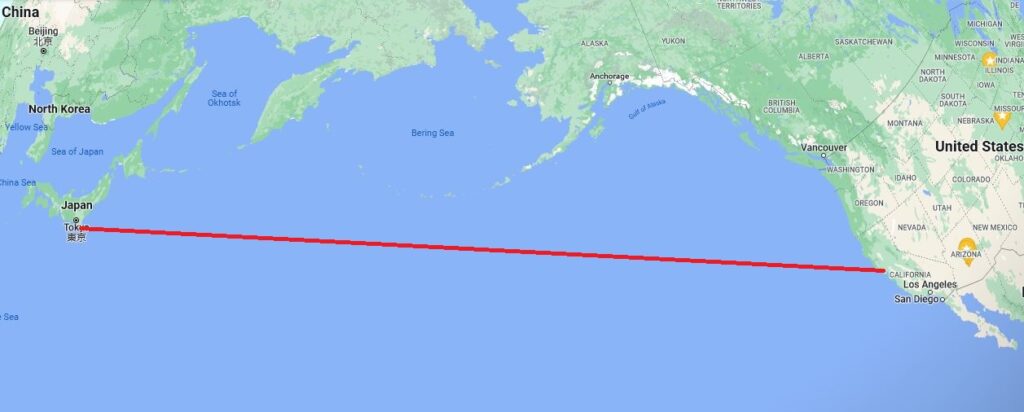

They arrived there in time to board a train of the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad. That took them past several Iowa towns—Council Bluffs, Des Moines, Iowa City, and Davenport. At 4:00pm on the 10th, they arrived in Chicago, having come 20,063 miles on their journey, or 81.7% of the distance. Trouble was, they’d used 86.3% of the time.

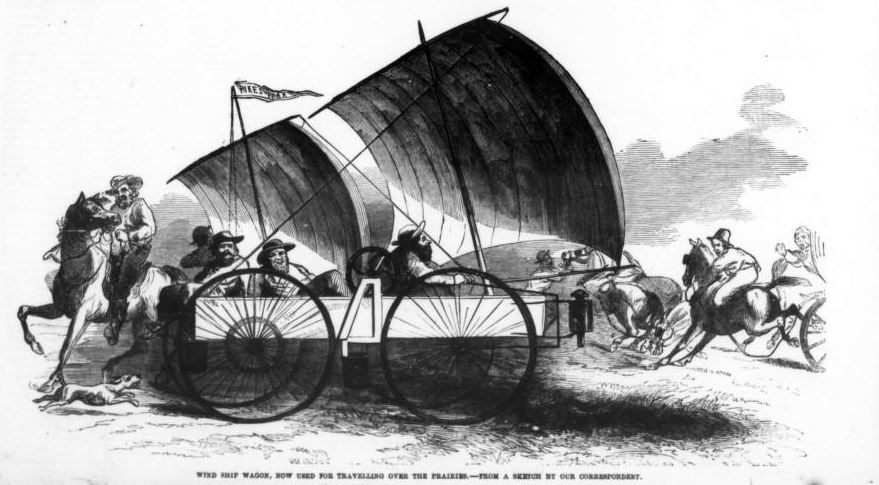

What about Mudge’s wind-powered sledge? Verne made it sound like Nebraskans used them all the time when heavy snow delayed the trains. Ice boats existed then, but I found no record of their use in the Midwest.

However, this site and this one both mention a wheeled wind-wagon built by Samuel Peppard of Oskaloosa, Iowa, who planned a trip to Pike’s Peak and visited—guess where—Fort Kearney in Nebraska.

An article in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, dated July 7, 1860, contained an article on page 104 titled “The Wind-Ship of the Prairies,” datelined Fort Kearney, May 27, 1860. The wind-wagon’s four-man crew declared Pike’s Peak as their destination. Could Verne have read a French translation of that article and replaced wheels with sled runners?

The company Verne called the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad had changed its name in 1866 to the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad Company. That railway became the inspiration for the song, “Rock Island Line.” The company ended in 1980.

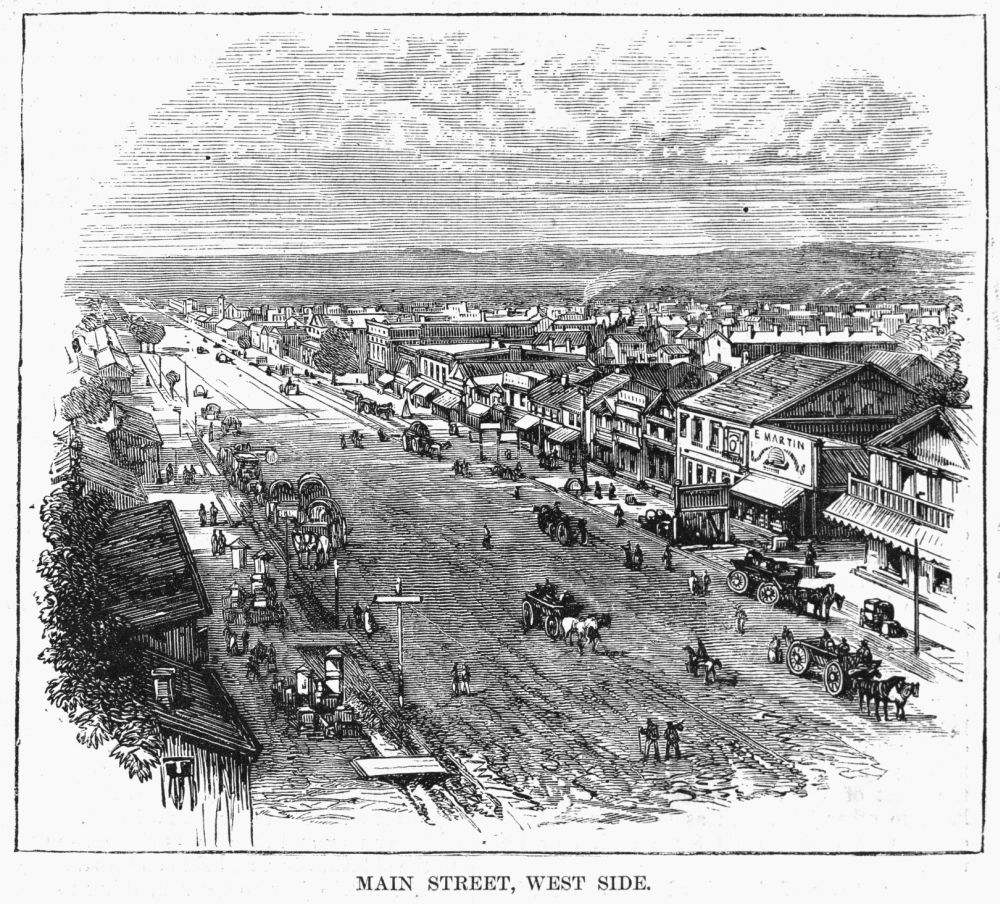

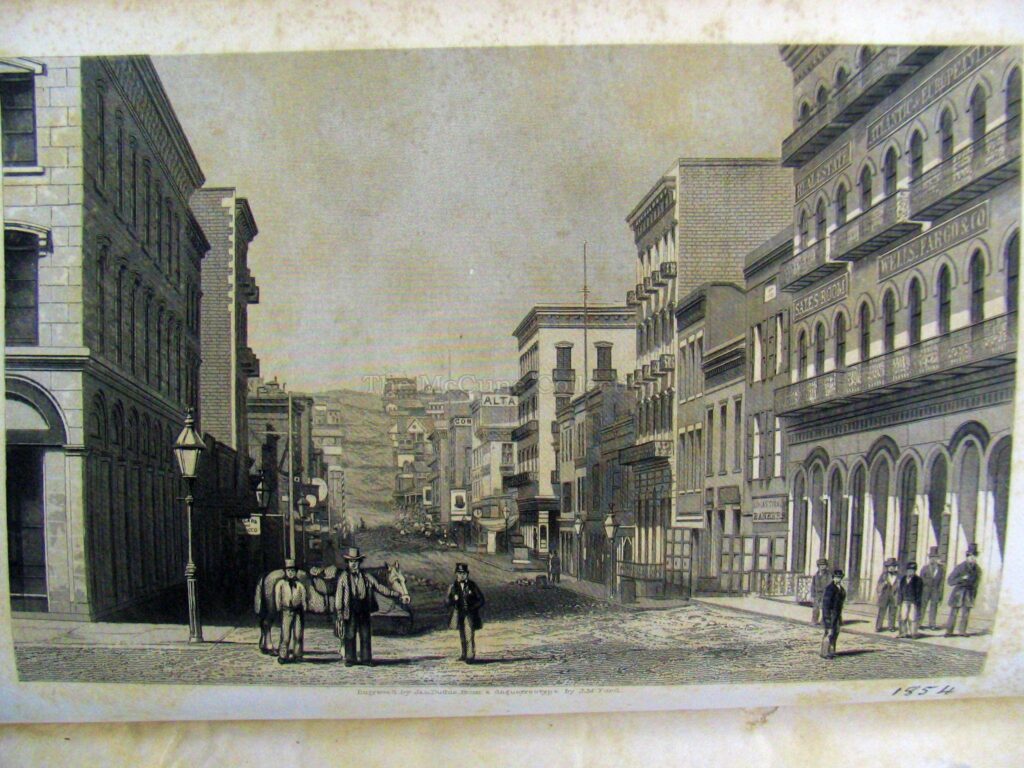

Fogg spent little time in Chicago, and Verne noted the city had “already risen from its ruins.” That refers to the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, an event no doubt fresh in his readers’ minds.

By 1872, Chicago’s population numbered nearly 300,000 people and Joseph Medill served as its 26th mayor. Today, some 2,756,546 people call it home and Lori Lightfoot is its 56th mayor.

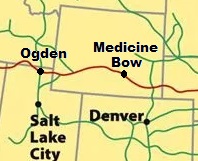

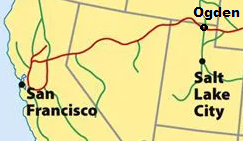

Fort Kearney no longer exists, but you can take a two-hour flight from nearby Lincoln to Chicago. Or you could drive ten hours along Interstate 80. I’ve mentioned that highway a few times now, and you might think it traces the route of the Transcontinental Railroad. It does. According to this site, the following routes form almost identical paths: California Trail, Mormon Trail, Pony Express Trail, Transcontinental Telegraph Line, Transcontinental Railroad, Lincoln Highway, the First Transcontinental Telephone Line, the First Transcontinental Airmail Route, and Interstate Highway 80.

Regarding screen adaptations of the novel, see my previous post for my favorite. For my second favorite, I’d pick the 1989 NBC TV miniseries starring Pierce Brosnan, Eric Idle, Julia Nickson, and Peter Ustinov. It’s been years since I saw it, but I recall being pleased with it.

With the four travelers reunited, they still stand a chance of arriving in New York in time to board the steamer to Liverpool. Watch this space for further updates from your entertaining and informative correspondent—

Poseidon’s Scribe