We’ve come to the third principle in Michael J. Gelb’s remarkable book, How to Think Like Leonardo da Vinci. In recent blog posts, I’ve been relating each principle to fiction writers, encouraging you to think like Leonardo as you write.

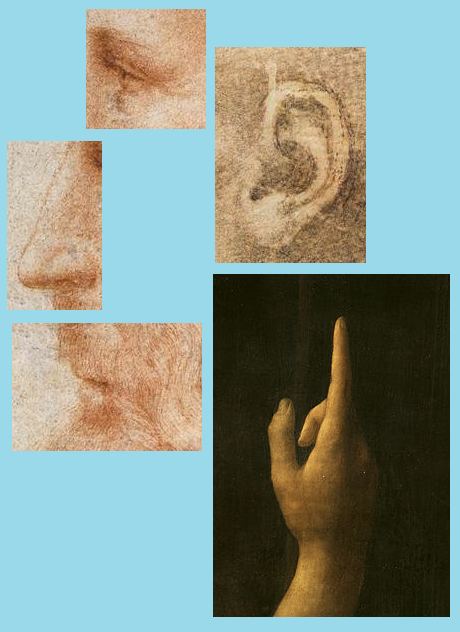

The third principle is Sensazione, which Gelb defines as “the continual refinement of the senses, especially sight, as the means to enliven experience.” Leonardo knew that we experience life through our five senses; therefore, only the person who could enhance his or her senses in perception and accuracy could experience life fully.

The third principle is Sensazione, which Gelb defines as “the continual refinement of the senses, especially sight, as the means to enliven experience.” Leonardo knew that we experience life through our five senses; therefore, only the person who could enhance his or her senses in perception and accuracy could experience life fully.

Da Vinci’s sight and hearing were superb, and he worked to improve all his senses. He regarded sight as the most important, following by hearing.

The exercises in the Sensazione chapter of Think Like Leonardo da Vinci are among the most fun in the book. For example, Gelb suggests you smell and taste things while blindfolded until you can identify each odor and taste, even those with only slight differences.

How does this relate to writing? The Point of View character in your story also experiences life through her or his senses, just as real people do. However, the only way you can convey these sensations to your reader is through words.

I’ve blogged about the senses before, and encouraged you to incorporate all five of them in your stories. To apply Sensazione in your writing, you must choose words that precisely convey the sensations experienced by your POV character.

I don’t necessarily mean you should pile on adjectives like beautiful, pungent, sonorous, delicious, and velvety—or adverb forms. Adjectives (and to a lesser extent, adverbs) can be useful if you’re selective and choose just the most apt one. Some adjectives, like “beautiful” and “delicious” are not distinct; they tell rather than show.

Another method is with metaphors and similes. If you can compare the sensation your character is experiencing with something to which the reader can relate, and make the comparison distinct and descriptive, that’s Sensazione.

As Leonardo knew, sight is the primary sense for humans, and so it will be for your characters most of the time. But if you appeal to the other senses, too, it can only enhance the reader’s enjoyment. Also, there are times when a character’s first sensation is through one of the other senses, such as when a sight line is blocked and the character hears or smells something before seeing it. Your character might be blind, or in darkness, and will have to rely on the other four senses.

If you work to cultivate your senses in your own life, by going through Gelb’s recommended exercises, you should also strive to become more adept at describing each feeling and sensation in words. As your skill improves, readers will be drawn into your stories and connect with your characters’ experiences.

Ah! I see, hear, and smell breakfast being prepared. I’ll have to end this post now, for soon I shall feel the fork in my hand, and a succulent repast will be tasted by—

Poseidon’s Scribe