Earlier I blogged about writer’s block, but focused on symptoms and causes. Today, let’s talk about getting over it.

As before, I’ll limit the discussion to minor writer’s block (minWB), the short-term state of being stuck while in the middle of a writing project. I’ll blog about Major Writer’s Block (MajWB) another time.

As before, I’ll limit the discussion to minor writer’s block (minWB), the short-term state of being stuck while in the middle of a writing project. I’ll blog about Major Writer’s Block (MajWB) another time.

My many fans—both of them, actually, including my Dad—will recall that I stated there are several types of minWB, which I divided as follows:

- Story-related problems

- Writing-related problems, but not about the story

- Personal, but non-writing, problems

I also stated that if you pinpoint which problem you have, that suggests a cure. For story-related problems such as plot, character, setting, or others, here are a few things you can try: (1) set the story aside awhile and let your subconscious (your muse) work on the problem, (2) try sketching a mind-map of the problem and creatively come up with multiple solutions, then select the best, or (3) ask your critique group or beta reader for help.

The craft-related problems all boil down to matters of attitude leading to negative mental associations, leading to stress. Since one type of craft-related problem is the pressure of the audience seeming too close, I have to point out what some might consider a contradiction in the advice I, Poseidon’s Scribe, have given out. In this blog entry I suggested, if you’re feeling the ‘presence’ of the reader too intensely, just forget about that audience and write freely for yourself.

However, just two weeks ago I urged you to keep the reader in mind, always.

Which advice is right—ignore the reader or be ever mindful of the reader?

(Aside: witness the clever way I get out of this paradox.)

I was right both times. In general, it is always wise to acknowledge that you’re writing to be read by others. Therefore, you should write with precision, avoiding ambiguity, so as to be understood. But if the fear of being criticized or disliked is paralyzing you into inaction, if the anticipation of bad reviews leaves you trembling before your keyboard, then forget about those readers for a while. Ignore them during your early drafts and focus on getting your story done.

Then in the later drafts, I suggest you visualize yourself as a sort of super-editor, far more critical of your own work than any reader could be, and yet able to fix every problem you find. In this way, you minimize your fear of the reader and substitute confidence in yourself.

That ‘visualization’ method may work for many of the minWB craft-related problems, by imagining a near-future version of yourself having already overcome the problem and working steadily on the story. Visualize yourself being in the flow, and once again gripped by the same enthusiasm you had when you first conceived the story idea. In this way you can change the mental linkages you’ve developed and re-associate writing with fun, success, and confidence rather than stress, fatigue, and inadequacy.

As to the last category of minWB, that of personal problems such as illness, depression, relationship difficulties, or financial woes, you need to confront those problems head-on first. Until you have a plan for solving them, and start to execute that plan, it will be tough to concentrate on writing.

Do these suggested cures work for you? Do you know of others I should have recommended? Unblock yourself and leave a comment for—

Poseidon’s Scribe

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction.

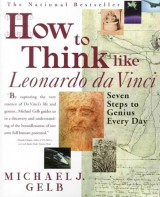

True, Leonardo da Vinci was an anatomist, architect, botanist, cartographer, engineer, geologist, inventor, mathematician, musician, painter, scientist, and sculptor. Arguably he was the greatest genius of all time. But…he never wrote fiction. In his book

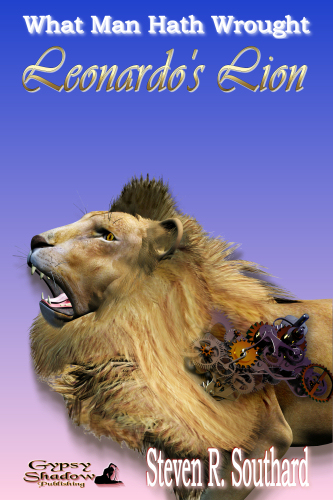

In his book  At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,

At this point, I can’t resist a personal plug. Leonardo da Vinci is such a fascinating historical figure, I wrote a story about the mechanical automata lion he constructed for the King of France. Had that been all da Vinci did, it would have been achievement enough, far beyond the norm of the day, but it’s barely a footnote in any list of his accomplishments. My story,  experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.