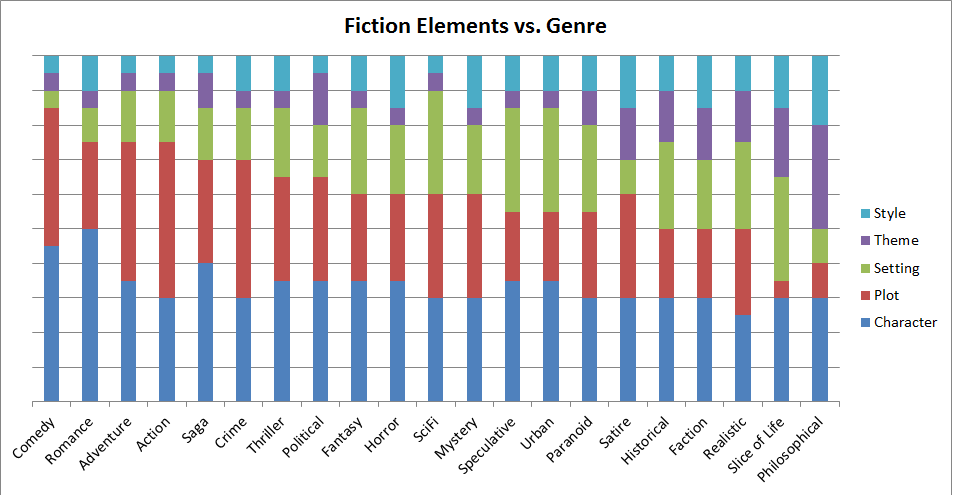

In earlier posts I’ve blogged about the various elements of fiction (Character, Plot, Setting, Theme, and Style). I’ve also blogged a bit about the various genres of fiction. Here I thought I’d explore how the various genres emphasize certain elements and de-emphasize others.

For the chart, I used the genres listed in the Wikipedia “List of Genres” entry. As the entry itself points out, people will never agree on this list. Even more contentious will be my rankings in the chart for how much each genre makes use of each fiction element.

For each genre, I assigned my own rough score for each fiction element. I’ve placed the genres in approximate order from the ones emphasizing character and plot more, to the ones emphasizing style and theme more.

For each genre, I assigned my own rough score for each fiction element. I’ve placed the genres in approximate order from the ones emphasizing character and plot more, to the ones emphasizing style and theme more.

Go ahead and quibble about the numbers I assigned. That’s fine. There’s considerable variation within a genre. Also, the percentages of the elements vary over time. If we took one hundred experts in literature and had them each do the rankings, then averaged them, the resulting chart would have more validity than what I’m presenting, which is based on my scoring alone.

But the larger point is that the different genres do focus on different elements of fiction. In my view, character is probably the primary element for all but a few genres. Theme is probably the least important, except for a limited number of genres.

Of what use is such a chart? First, please don’t draw an unintended conclusion. If you happen to know which elements of fiction are your fortes, and which you’re least skilled in, I wouldn’t advise you to choose a genre based on that.

Instead, look at the chart the opposite way. Find the genre in which you’d like to write, and work to strengthen your use of its primary fiction elements in your own work. You might even glance at the genres on either side of your favorite one and consider writing in those genres too.

I can’t seem to find online where anybody else has constructed a chart like mine. Perhaps the only one you’ll see is this one made by—

Poseidon’s Scribe

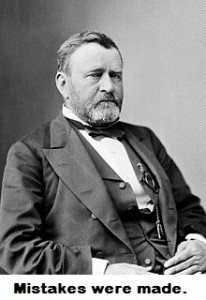

Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).

Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).