Years ago, while reading Zen in the Art of Writing by Ray Bradbury, I was struck by a memorable passage. He’d titled the fourth chapter “Drunk and in Charge of a Bicycle.”

After stating that he’d read how other authors found writing a difficult chore, Mr. Bradbury wrote:

But, you see, my stories have led me through my life. They shout, I follow. They run up and bite me on the leg—I respond by writing down everything that goes on during the bite. When I finish, the idea lets go, and runs off.

But, you see, my stories have led me through my life. They shout, I follow. They run up and bite me on the leg—I respond by writing down everything that goes on during the bite. When I finish, the idea lets go, and runs off.

That is the kind of life I’ve had. Drunk, and in charge of a bicycle, as an Irish police report once put it. Drunk with life, that is, and not knowing where off to next. But you’re on your way before dawn. And the trip? Exactly one half terror, exactly one half exhilaration.

Always fun to read Bradbury; even his nonfiction hums with an electric rhythm. But today I thought I’d examine his metaphor a bit, since it has stayed in my mind for at least a decade.

I understand why it appealed to Bradbury. First, the phrasing is a bit odd to American ears, and he often sought interesting new ways to express ideas. Second, I’m sure he had a distinct mental image of what it would be like to be drunk and in charge of a bicycle. That idea of going somewhere but not knowing where; the wobbly, weaving way you’d be ever on the edge of falling. Bradbury saw that as being akin to his writing experiences.

I understand why it appealed to Bradbury. First, the phrasing is a bit odd to American ears, and he often sought interesting new ways to express ideas. Second, I’m sure he had a distinct mental image of what it would be like to be drunk and in charge of a bicycle. That idea of going somewhere but not knowing where; the wobbly, weaving way you’d be ever on the edge of falling. Bradbury saw that as being akin to his writing experiences.

Third, I’m sure he enjoyed the concealed contradiction, the playful paradox, inherent in the words “drunk, and in charge.” There’s no doubt the bicycle rider is going where the bike goes. If arrested, there’s no doubt whom the police would hold responsible. But who, after all, is really in charge? If you’re drunk, as Bradbury says, with life, then you’re in the grip of events beyond your “charge” and it’s your stories that are leading you.

That muse of yours, then, is the one in charge. You follow where she beckons even when that way seems outlandish or bizarre, because she’s never steered you wrong before. You’ve no idea where you’ll end up, and the notion of ceding control leaves you with that mix of half terror, half exhilaration.

But when you submit your story before the squinty eyes of the editor, when it’s picked over by readers and critics, where is the responsibility then? It’s only your name on the story; the muse has vanished, gone on to her other affairs. Like the drunk bicyclist trying to explain himself to the constable, you can’t point the finger elsewhere.

When I set out to write about this topic today, my aim was to poke holes in the Bradbury’s metaphor, to state that my writing experiences weren’t like that at all. Especially the half terror part. I was going to create my own metaphor for my writing life. I wanted to capture the godlike act of creating a world, of designing the initial conditions, then winding up the characters and letting them go, interacting and confronting their problems. All the while, that godlike me would be taking notes, watching these wind-up characters’ every move. If I did my creative job well, readers would enjoy the result. If not, well, back to the drawing board to create another world peopled with other wind-up dolls.

But instead of condemning Bradbury’s metaphor, I’ve praised it. From his grave, he laughs at the irony of it. I thought I was in charge of this blog, thought I had it all planned out. Now I see I’ve been drunk and in charge of a bicycle, in the grip of other forces. Yet the one person responsible, the name at the end is—

Poseidon’s Scribe

Sorry, I haven’t read all your books and stories. I’ve read less of your canon than I have of Jules Verne’s, Isaac Asimov’s, or Robert Heinlein’s. But, oh, the few of your books I digested left lifelong mental imprints: Something Wicked This Way Comes, Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, The Illustrated Man, Now and Forever, and The Martian Chronicles. In high school, I read your short story, “The Flying Machine,” and my recollections of it inspired my story, “The Sea-Wagon of Yantai,” written decades later.

Sorry, I haven’t read all your books and stories. I’ve read less of your canon than I have of Jules Verne’s, Isaac Asimov’s, or Robert Heinlein’s. But, oh, the few of your books I digested left lifelong mental imprints: Something Wicked This Way Comes, Fahrenheit 451, Dandelion Wine, The Illustrated Man, Now and Forever, and The Martian Chronicles. In high school, I read your short story, “The Flying Machine,” and my recollections of it inspired my story, “The Sea-Wagon of Yantai,” written decades later.

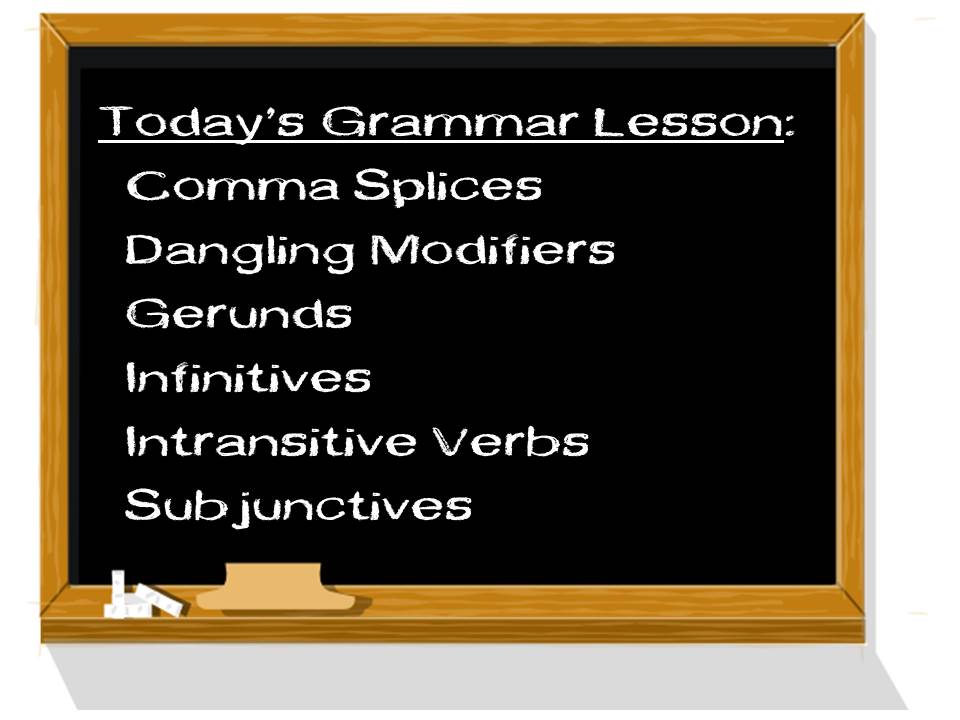

It’s important for a fiction writer to learn how to describe human facial expressions. A person’s face is the most communicative body area, and often it reveals a character’s feelings. Amazing, isn’t it, how many things we can make our faces do! There may be as many facial aspects as there are possible mental states.

It’s important for a fiction writer to learn how to describe human facial expressions. A person’s face is the most communicative body area, and often it reveals a character’s feelings. Amazing, isn’t it, how many things we can make our faces do! There may be as many facial aspects as there are possible mental states.