Words can heal, and inspire others. Today let’s meet a writer who crafted poems to help her through a terrible experience, and whose words might lift you from a bad place, or just help you understand life through her insights. I met Amanda Russell at an Afternoon with Authors event at a local bookstore. In her responses to my questions, you’ll learn about travel, grief, book covers, gardening, and more. Here’s her bio:

Bio

Amanda Russell is an editor for The Comstock Review and webmaster for the Fort Worth Poetry Society. Her poems appear or are forthcoming in The Shore, Gulf Stream Magazine, Pirene’s Fountain and elsewhere. Her poem “The Blizzard of 1888” was a finalist for the 2024 Kowit Poetry Prize, selected by Ellen Bass. Amanda has two poetry chapbooks available.

Interview

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing poetry?

Amanda Russell: I don’t know how young I was, but I wrote poems as a young child. Mostly to deal with the changes in family that result from divorce and remarriages. I continually felt lost and out of place as a child, both in the context of my own family and the communities I was nurtured in. I had trouble saying my thoughts out loud and writing came more naturally for me. I kept my poems to myself, but by the age of 14, I knew poetry would be a constant in my life.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books or poems?

A.R.: In 9th grade, my theater teacher gave me a copy of “Letters to a Young Poet” by Rainer Maria Rilke. There, I found my forever writing prompt. Rilke says to put into your poems the images and themes you find in your life and dreams, to approach the world as if seeing it for the first time every time. This is something I go back to anytime I feel like I don’t know what to write. It’s like Jane Hirschfield, Mary Oliver and Ocean Vuong all talk about, paying or investing attention. And I find myself drawn to writing like this.

The first poetry book I bought was Mary Oliver’s Dream Work. Then, Louise Gluck’s The Wild Iris and Stanley Kunitz’s The Wild Braid. My influences continue to broaden the more I read. There’s Jim Harrison and Marie Howe and Li-Young Lee who I love to read. A few of the poetry collections on my top shelf are Ellen Bass’s “The Human Line,” Ocean Vuong’s “Time is a Mother” and Ruth Stone’s “Simplicity.” And I just discovered Blas Falconer, who I am excited to read more from.

I love listening to YouTube poetry readings as well. In fact, that is how I usually discover new poets. One poet will mention another poet, and I go look them up. The journey is delightfully endless.

P.S.: You’ve lived, I believe, in Nebraska, New York, Florida, New Hampshire, and now Texas. Did your poems change character as you moved around? Was one state more conducive to writing poetry than another?

A.R.: I have never actually lived in Florida. But, I did connect with some poets from there during the pandemic through Zoom open mics while I was living in New York. I have lived in all those other places though. I grew up in East Texas, and if I had never moved away, I would not be the person I am and therefore would not be writing the poems I am writing.

Yes, the poems changed with each place! In addition to the changes occurring within me, each new place has different immediate surroundings, sounds, plants and animals. One poem from NH references the blue spruce I saw outside my window each morning on Mill Street, another mentions the neighbor’s dog barking. For east Texas, the red dirt, the pines. For NY, maples and snow. After moving to NH, I remember telling a friend from NY that I met a family of hooded skunks on one of my afternoon walks. He said that proves you are in a different ecosystem, and we got a good laugh. Oh yeah, and basements! That’s a NH reference for me since our rental had one. I experienced seasonal depression up north for so many years that I just thought it was normal. But I don’t get it as much in Texas. In Fort Worth, I find myself referencing trains and mosquitoes.

Also, with each new home, there are new poets. So, in Nebraska I discovered the work of Ted Kooser. In New York, I found a vibrant poetry community and attended their readings regularly. Moving to New Hampshire, I delved into the poetry of Jane Kenyon, even visiting Eagle Pond Farm and interviewing Mary Lyn Ray who knew Jane Kenyon and Donald Hall during their lives. That interview was published by South Florida Poetry Journal in February 2025. Moving back to Texas has been interesting. And I am still finding my way into the poetry community here. So, I hope no one place is better than any other for writing poems. I want to write poems regardless of where I am!

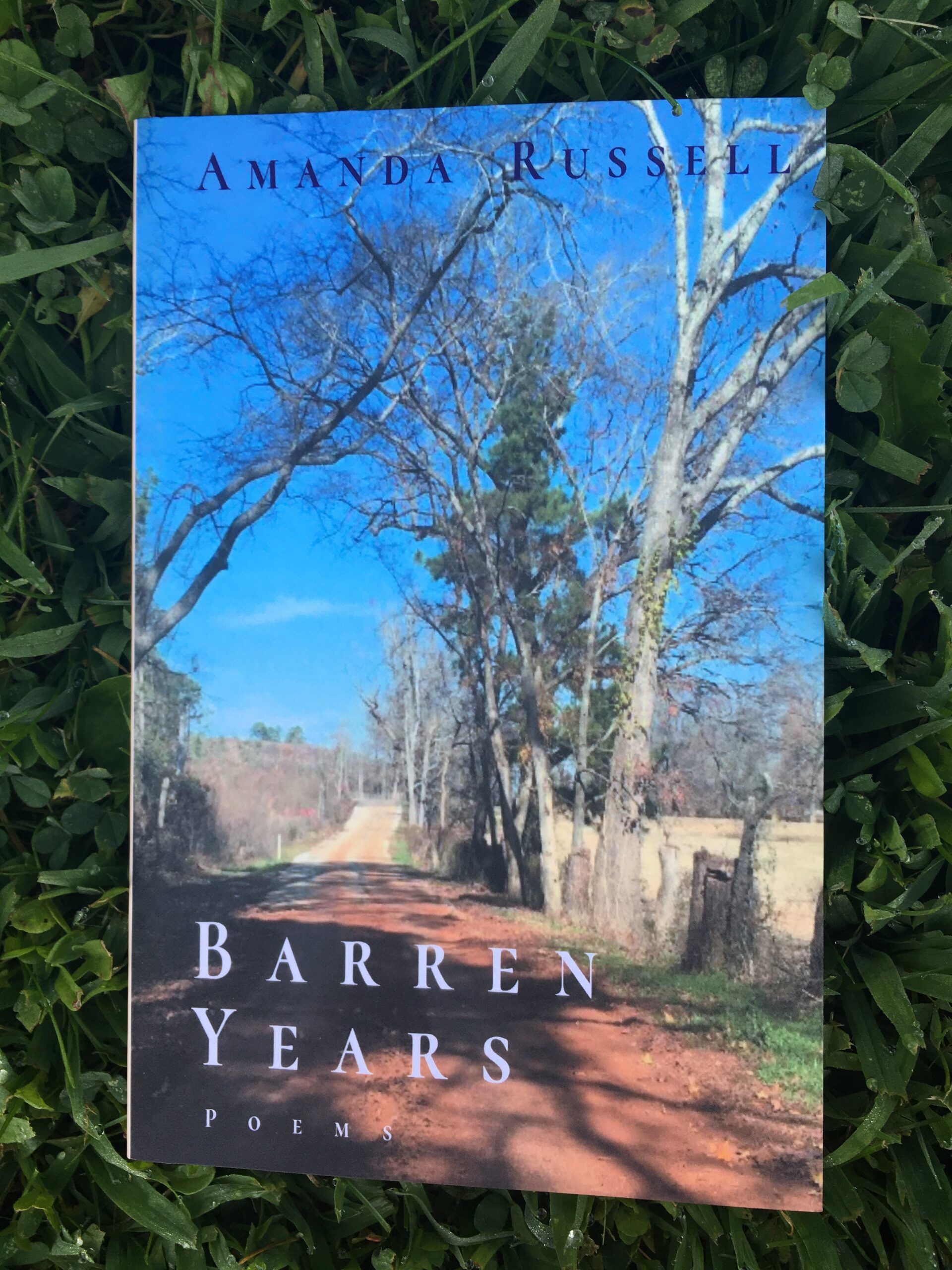

P.S.: I’m so sorry about your devastating miscarriage of twins. Your poetry collection Barren Years resulted from that. Yet others have described the book as consoling and even upbeat. Tell us about the process of writing the poems for that book.

A.R.: The oldest poem in that collection is “Sonogram” which came to me about 8 months after the miscarriage. I hadn’t been able to vocalize what had occurred. I had tried, but there would just be silence. When I wrote that poem, I slammed my notebook shut and threw it across the room. I never intended to share it. After moving to Nebraska, I was determined to gather my poems into some kind of collection. By the time I got to New York, I had whittled the group of 80 poems down to 25. I was still not sure if I would want to publish it. Then, I shared it with a friend. After reading it, she met me at a coffee shop and said, “I didn’t know we had this in common.” She said reading my poems helped her process her grief around the miscarriage she experienced years ago. She encouraged me to publish the poems so other people could read them and feel less alone. Maybe that is how it is consoling.

Miscarriage is not talked about as often or as openly as it needs to be. Because of that, many women go through years in silence thinking that they are alone. Every time I give a reading from Barren Years, people reach out to me afterwards to say, “This happened to me too.” And it’s like sharing a secret. There’s a deep and immediate understanding and healing energy that exchanges, strengthening both people. It’s life-changing to know you are not alone.

Barren Years covers a seven-year span of time and uses gardening as an external mirror for the process of healing though the writing of poetry. There’s many references to conversations. I’d say one of the themes— in addition to love, loss, grief— is communication. One thing about me is that I often get bored reading books, so variety is essential for my engagement. So, I think that’s how a book about a miscarriage can be also about many other things.

P.S.: What common attributes (settings, themes, etc.) tie your poetry together or are you a more eclectic poet?

A.R.: I am disinterested in being a “certain kind” of poet writing a “certain kind” of poem. I am inspired by writing that discovers something. So, in that regard, I am more eclectic and always exploring.

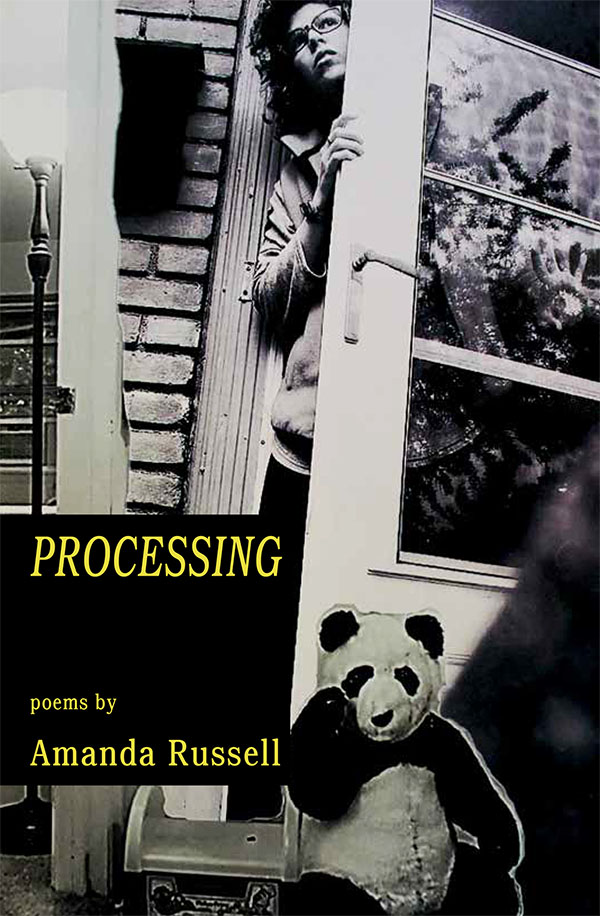

P.S.: Regarding your poetry book Processing, one reviewer described it as brave, resolute, mesmerizing, and miraculous. Another said the poems reflect “deeply aching, beautifully rendered pleasures and pains.” Please tell us your thoughts on the book, and what themes link the included poems together.

A.R.: Processing to me is a book about my experience as a stay-at-home mom. It offers a different perspective than the mainstream idea maybe. For me the experience was lonely and difficult. It was like my life was on halt while I surfed this constant learning curve. And I don’t know how to surf either. And I did not have some huge career ambitions before having kids. I was just a cashier and was trying to write poems every day.

The thing is, I lost my identity when I became a mother. At first it felt natural, even unnoticeable, to let it go. But then, years passed. And I’d forgotten what kind of music I liked to listen to. I wasn’t enjoying my life because I wasn’t living my life.

So, Processing is the collection in which I venture back into the country of myself and find footing. I am looking for and reconnecting with myself. In these poems, I find the courage to speak about both the love and loneliness of motherhood and marriage. In my poems, relationships are important, and there is this sense that I am reaching deeper into my own life to hopefully connect with others as well.

P.S.: I’m intrigued by the covers you’ve chosen for your books. The mostly barren trees and lonely road make sense for Barren Years. However, can you explain the symbolism, if any, in the cover to Processing, with the woman (you) peeking around a door, and a stuffed panda on the ground?

A.R.: Actually, I cut the poem that references the panda from the collection. Like others that didn’t make it, it just was not finished in time and the collection felt solid without it. But, I chose to keep the panda on the cover because I liked him there. My son named him Tao Tao and used to wrestle him after school.

But when I decided to collage part of the inside of the house on the left side of the book, I used a sliver of my son’s room. His lamp, window unit a/c, footstool and panda were all there. I did not stage it. I wanted things to appear as they were.

And, the central image of me looking out the door was my concept photo for the book when I was beginning to write this collection. That’s the front door of our townhouse in Cornwall, NY. I did not have anyone to hold the phone to take the picture, so I used the front camera to make a short video. It was raining. I sat the phone in a pot of spinach and pressed play. That black part in the lower right corner would be green if the cover were in color. It’s a spinach leaf.

So, what you see is a screenshot out of that video. There is a whole story of how we got the image to something usable for the cover.

Also, I debated whether to put my face on the cover of my book. I decided to do it because one of the poems in the book is written in response to an article on mothers and autism and the concept of blame; and the mother in the graphic paired with that article does not have a face. I wanted to in some way put a face on her. It’s not her face, but it’s the only one I have. I decided to put my face on myself in my role, to claim it. I am just wearing whatever I was wearing, the fleece vest is pink and I still wear it often, lol. So in that way, it’s all quite candid.

P.S.: Where do you get the ideas for your poems?

A.R.: I get them from the edges of sleep and what I see as I drive from the gym to work. I get them from whatever pops into my head when I’m in the shower or cooking dinner. From what my kids say and do. It comes from what I long for or need to dig into. I find them in the mailbox or growing in the garden. From what I read. I often write immediately after reading. If I am stuck, I ask my subconscious to work on that while I sleep. I use prompts sometimes with varying results. Natalie Goldberg’s Writing Down the Bones introduced me to timed writing sessions which I use because I am often pressed for time as a working mother of two school-aged children. I use it all, even tarot cards. Anytime a line arrives, I try to catch it on paper (or audio or email) without judging its potential because that shuts it down.

P.S.: You list gardening as an interest and many of your poems involve plants and the nature of growth. Do you do your gardening when stuck for words and find the solution to writer’s block there, or does gardening provide the initial inspiration for fresh poetry?

A.R.: Yes. Anything to get the blood flowing is often great for generating ideas. I love my garden. I love to sit in it and pretend to be a little plant. I go there for energy and encouragement, for consolation when I am down or company when I am happy. I read a question from Stanley Kunitz’s “The Wild Braid” in which he asks if it is any easier to deal with loss and death in the garden than in the rest of our life. I have pondered that question. I still ponder it. I think we could add to that, transition and blooming, sprouting and thirsting.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of poetry for you?

A.R.: The easiest part of poetry is reading other people’s poetry. Writing is difficult and full of hope and despair. I write because if I didn’t, I may entirely miss my life. Writing connects me more deeply to my life and the relationships that fill it.

P.S.: You’ve said some poems require little revision, and others take years. How many poems are you working on at any given time?

A.R.: LOL. Yes, I work on several at a time. Actually, I work on all the poems, all the time. There’s a saying that poems are never finished, just abandoned. I am not sure I completely agree with that, but if years later, I see an improvement I could make, I would consider it.

I strive to write poems which were not possible to put into words before they were written. As such, the process is often slow and iterative. Many times, I am trying to write something that I may not learn for several years. Andrea Gibson has a poem called “What do you think about this weather?” in which they use the metaphor of a mother knitting mittens for a child a size (or two) big so they can be worn longer. They say, “I feel that sometimes when I’m writing poems— like they don’t yet fit. Do you ever feel like the best of you is something you’re still hoping to grow into?” So, I approach the poem again and again. It’s not unusual for me to have 40 or even 60 plus revisions on a single poem. Some of those revisions are total rewrites.

I keep writing and rewriting until the poem speaks back to me. Once that happens, the process is that of listening, following, and trusting the poem itself more than “writing.”

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring poets?

Amanda Russell:

- Read widely. Write as much as you can.

- Go to open mics in-person or online, listen to other poets, and share your work. Learn about revision.

- Say Yes to any opportunities you are given.

- Listen to constructive comments with the aim of learning more about crafting poems that work to their fullest potential.

- Learn to listen to the poem when it asks you to go places and learn things that you did not anticipate.

- Surround yourself with the people who encourage and inspire you.

- Trust your voice. Trust your reader. Trust the process.

And I will end with one of my favorite quotes from Rainer Maria Rilke’s book Letters to a Young Poet, “[T]ry, like some first human being, to say what you see and experience and love and lose. … seek those themes which your own everyday life offers you; describe [them] with loving, quiet, humble sincerity … for to the creator, there is no poverty …” (Rilke Letters to a Young Poet).

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thank you, Amanda. That advice would work for prose writers, too!

Web Presence

Readers can find out more about Amanda Russell at her website, at the Fort Worth Poetry Society website, and on Instagram. A post by Brianne Alcala featured Amanda’s works, and Amanda read and discussed some of her poems on YouTube.

![Pageflex Persona [document: PRS0000039_00001]](https://stevenrsouthard.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/HidesTheDarkTower-DigitalCover-FINAL2-200x300.jpg)