Recently, in a meeting with my critique group, I criticized an author for using too many em-dashes (—) in a manuscript. This author then acquainted me with an interesting online disagreement.

First, author Kate Dyer-Seeley posted a well-worded defense of the Oxford Comma. I, too, am a fan of inserting a comma after the penultimate item in a list before the ‘and.’

Then, author Kristine Kathryn Rusch (who had once been Dyer-Seely’s instructor) countered with a post of her own. Her objection didn’t concern the Oxford Comma, but rather Dyer-Seely’s willingness to add or delete commas from her manuscripts based on an editor’s suggestions.

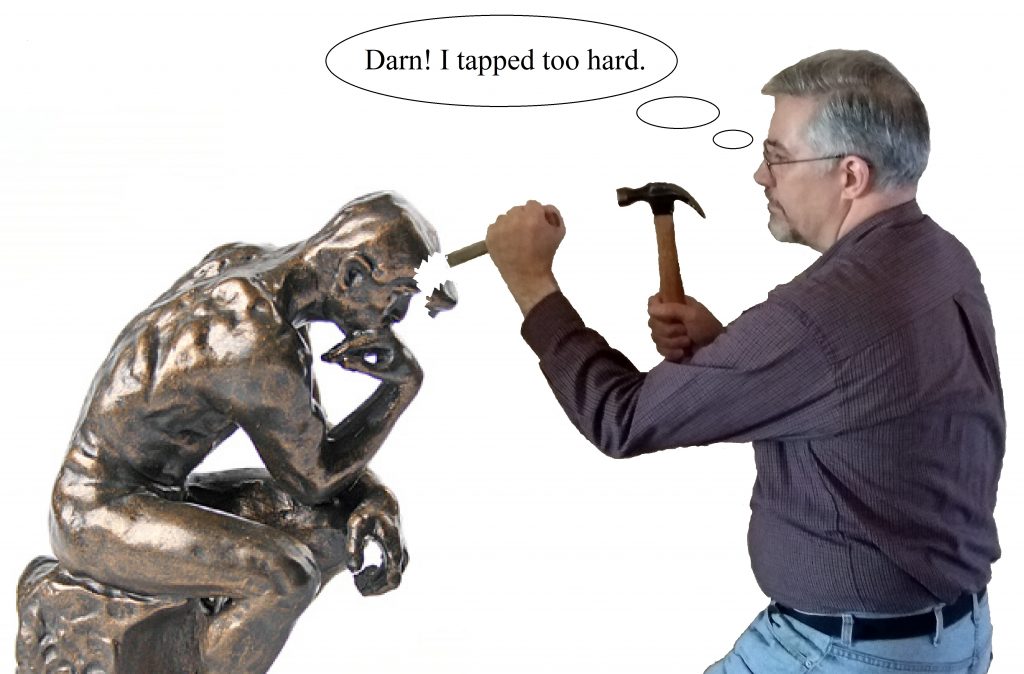

For Rusch, punctuation is a tool employed in the service of the story, and useful for conveying an author’s voice. Therefore, if you beak a punctuation rule and an editor suggests a revision, you should be able to defend your punctuation choices.

Who’s right?

Here’s a list of ten famous authors who violated, even spat on, punctuation rules without any harm to their reputation. They would side with Rusch.

To be fair, I’ve over-simplified Rusch’s position. She did say a writer must first learn the rules of punctuation before breaking them. We’ve heard that confusing advice before—learn the rules before you break them. Huh?

Here’s the catch, though. If you’re an editor (or a fellow writer doing a critique), it can be difficult to distinguish whether the writer’s flouting of the rules is part of the writer’s style and is meant to serve the story, or if the writer broke the rules out of haste, laziness, poor self-editing, etc.

If you’re a beginning writer still struggling to find your voice, the recommendations of an editor can seem like a burning-bush pronouncement, complete with stone tablets. It can be intimidating to fight back and defend every punctuation violation, as Rusch advocates.

Until recently, I’d never understood the editorial side of the business, but as a first-time co-editor of an upcoming anthology, I’m beginning to appreciate it. Any submitted manuscript does provide certain clues about why a writer broke a rule.

For instance, are there other mistakes? Are there misspellings and grammatical errors that fling a reader out of the story? If so, chances are the writer lacks a defendable rationale for breaking punctuation rules.

On the other hand, as an editor, did you breeze through the story, caught up in the writer’s world, and only notice punctuation violations upon re-reading? If so, you know this author has an established voice, a solid command of when to break rules. Edit such a story with a light touch.

Rusch’s position is a strong one, and it should be the goal of every fiction writer. Convey your story using your voice. If that means breaking some rules, do so, and stand ready to defend your choices.

Not apologizing for this final em-dash, I’m—

Poseidon’s Scribe

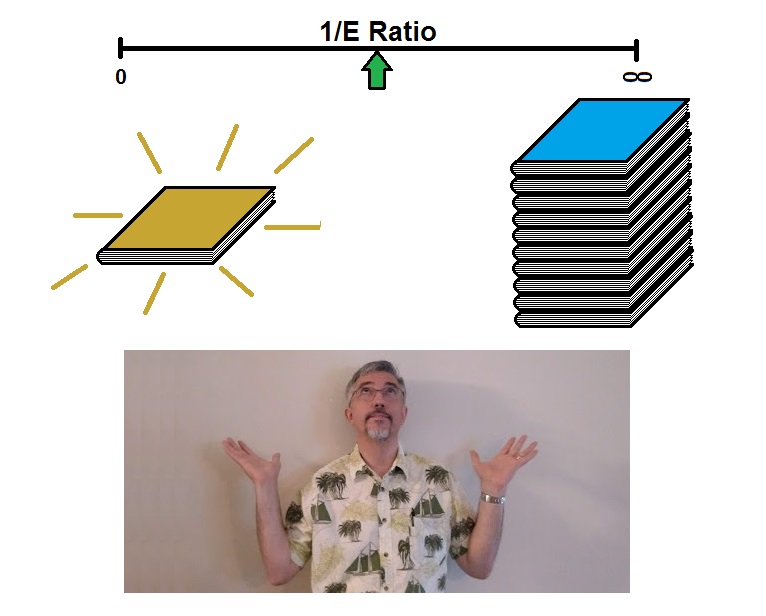

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

At one extreme, 1/E could be very small. In this case, you might spend twenty years polishing a novel, editing and re-editing draft after draft. Your final product might be very good and might become a classic, but you couldn’t repeat your success too many times.

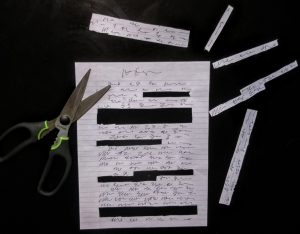

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

Allow me to define what I mean by censorship. It’s the deliberate alteration of text, without the author’s permission, to make the story less offensive to the censor. This is not what a normal editor does. Editors collaborate with authors to correct errors, to make the book as good as it can be.

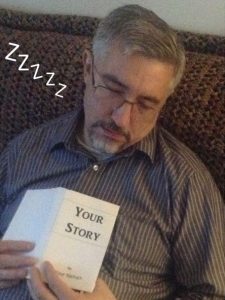

Let’s say you’re looking over the story you just finished writing and you see a section where the action really drags. While writing, it seemed necessary to describe a scene fully or explain a character’s backstory so later plot actions would make sense. Now you’re torn. Should you follow Hitchcock’s advice and just cut that section, or leave it in at the risk of boring your readers?

Let’s say you’re looking over the story you just finished writing and you see a section where the action really drags. While writing, it seemed necessary to describe a scene fully or explain a character’s backstory so later plot actions would make sense. Now you’re torn. Should you follow Hitchcock’s advice and just cut that section, or leave it in at the risk of boring your readers?