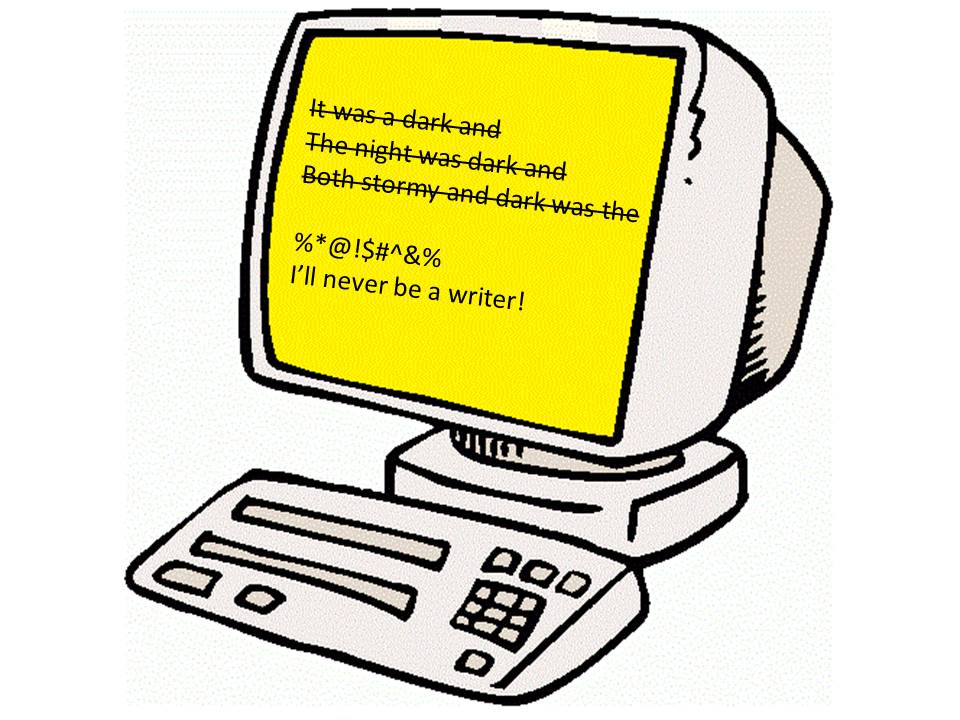

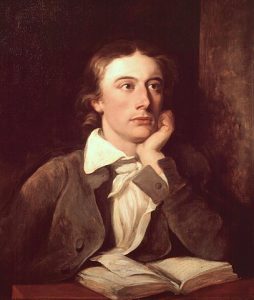

As part of our shared journey through the realm of fiction writing, let’s explore a few rooms within a stately mansion belonging to the English romantic poet, John Keats. In particular, what did he mean by the term negative capability, and how does it relate to creative writing?

Nearly two centuries ago, on December 21, 1817, Keats wrote a letter to his brothers where he mentioned negative capability:

“…at once it struck me what quality went to form a Man of Achievement, especially in Literature, and which Shakespeare possessed so enormously—I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason—Coleridge, for instance, would let go by a fine isolated verisimilitude caught from the Penetralium of mystery, from being incapable of remaining content with half-knowledge. This pursued through volumes would perhaps take us no further than this, that with a great poet the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration.”

That may be confusing, but here’s what I think he means—If you want to be a great writer, be willing to:

- delve into the essence of your characters (or objects, like a Grecian Urn),

- shed your preconceived world-view,

- abandon any search for meaning or the urge to fit things into a logical structure, and

- accept any mysteries and ambiguities you find without trying to resolve them.

Keats praises Shakespeare for the Bard’s ability to show us his characters, through their speech and actions, as they would be, without the author’s heavy hand fitting everything into a coherent whole. Keats criticizes Samuel Coleridge for starting with a philosophical vision and fashioning poetic characters to illustrate that vision.

Why did Keats call this approach ‘negative capability?’ The Wikipedia entry offers an electrical explanation. However, I believe Keats was saying that a true poet should negate her own capability (to make judgements; detect patterns; deduce from, or induce to, general principles) and instead immerse herself in the object of study and absorb all that is there, with all its contradictions and inconsistencies.

For those of you still stuck on the word ‘Penetralium’ in Keats’ letter, let me digress a moment. The word refers to a building’s innermost part, like a temple’s sanctuary. By extension, it can mean the secret inner essence of a person—the soul. Keats thought in terms of rooms of the mind, as illustrated by a letter he wrote, which is cited in the Wikipedia article: “I compare human life to a large Mansion of Many Apartments…”

For another description of negative capability, see this video with author Julie Burstein, especially from 1:00 to 1:25. Also, check out this post at Keats’ Kingdom, and this one by Dr. Philip Irving Mitchell of Dallas Baptist University.

As for me, I take a nuanced view of negative capability, as it regards creative writing. I agree writers should empathize with their characters, to know them as directly as possible. That keeps all the characters from seeming to be slight variations of the author. I also concur writers should embrace “uncertainties, mysteries, doubts.” The worldview of any character and even the universe of the story itself don’t have to fit neatly together in every detail. The writer should approach the characters and story with an open mind, allowing things to develop as they would in their world, not necessarily in step with the worldview of the writer.

But where Keats asserts “the sense of Beauty overcomes every other consideration, or rather obliterates all consideration,” I suggest this applies to the story as a whole, not just one character. Characters are not works of art for a writer to portray, however empathetically, in isolation. They are part of a greater whole, the story, and that whole—with its plot, themes, style, setting, and characters—is the thing the writer must strive to optimize for reader enjoyment.

I hope you liked our visit to this mansion of John Keats’ mind. It’s time to continue with the rest of the tour, led by your literary tour guide—

Poseidon’s Scribe