Tomorrow, the Martin Luther King Jr. Birthday holiday coincides with National Imagination Day. Appropriate, huh?

What is National Imagination Day?

Picture a day set aside to celebrate the unlimited power of your mind to think whatever it wants to, to dream impossible dreams, to imagine a better world (or a worse one). That’s National Imagination Day.

Who Started It?

The folks at NationalDayCalendar.com started National Imagination Day in 2024, just two years ago.

What, Exactly, Is Imagination?

Imagination—the ability to form mental images of things not detected by the senses or not considered real.

From out of nothing at all, we can form something in our mind—something new to the world. Or, from raw materials at hand (or those we can think of) we can picture a new formation, a new construct, a new use.

We think of it as a trait exclusive to humans, but animals imagine too. What might they be imagining?

How Do I Celebrate National Imagination Day?

Glad you asked. Here are a few suggestions:

- First, if you haven’t used your imagination in a while, you might need to prime your imagination pump. Let your mind return to a time when you imagined things with ease—as a young child. What did you imagine then? What did you pretend to be or do? Recall that time and remember the fun.

- Another priming technique—watch a movie or TV show, or (better) read a fiction book. (If you’re not sure which books to read, I can recommend some.) Imagine yourself in the settings of that story. Or think how you would direct the show or write the book in a different and better way.

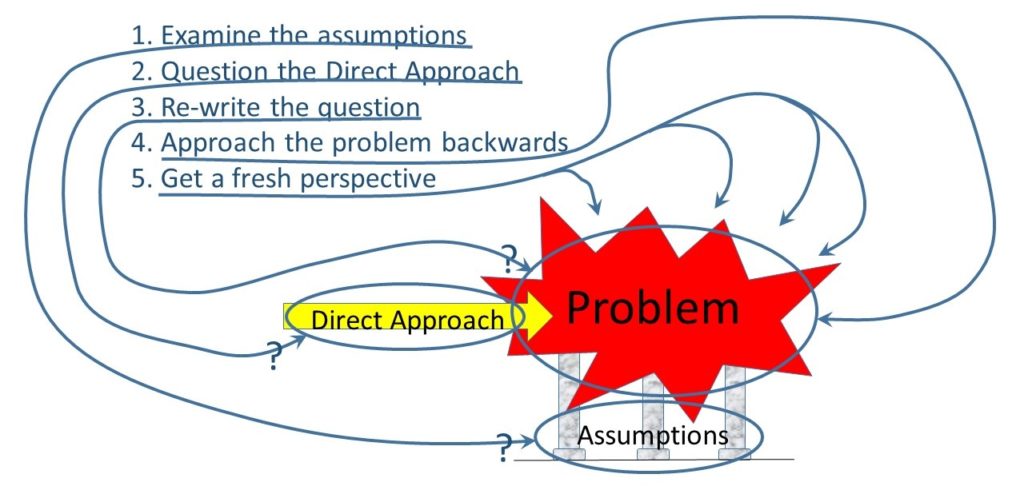

- Consider a problem you face in your life, or one someone else faces. Write twenty solutions to the problem. Don’t limit yourself to practical, feasible solutions. Go crazy, but don’t stop until you reach twenty of them.

- Take a walk in nature, maybe somewhere you haven’t walked before. Imagine an adventure there, with talking trees and animals, castles, wood sprites, or whatever.

- Compose a song, with or without lyrics. Sing or hum it. Dance to it. They say music is the language of the soul.

- Draw or paint a picture of whatever your mind imagines.

- Build an imaginative physical creation using whatever materials you have at hand.

- Write a story or poem about whatever your mind imagines.

- Imagine your ideal video game. Write the premise of the game and its major characteristics.

- Since we celebrate Martin Luther King Jr’s birthday on the same day, read his famous “I Have Dream” speech. Imagine the country of that dream. What would that nation be like? Imagine yourself there.

What’s the Point?

Whichever suggestion you chose, did you have fun? If so, why not do a little imagining every day? No need to wait a year.

Look back at what you did. Did your imaginative activity spark something bigger? Did you brainstorm a workable solution to the problem? Could you write that story, or screenplay, or poem, and could you submit it? Might that song be something you could record? Is the picture you made or the structure you built sharable with others? How about that video game—would someone in the industry be interested? What might it take to get our country to resemble the one in Martin Luther King’s dream?

Don’t be disappointed if you imagined something silly or stupid or too private to share with others. Some imaginative ideas lead to profitable outcomes, but most don’t. National Imagination Day isn’t about making money.

However, consider this—every profitable innovative idea, every new song or story or painting or video game started out in someone’s imagination. They imagined them on a day like today.

You have an imagination. Use it! Don’t let that powerful ability go to waste. Every day can be National Imagination Day for people like you, and for writers like—

Poseidon’s Scribe