You’re asking if you read that subject line correctly. Hold back? Aren’t writers supposed to explain things? Aren’t they supposed to…you know…write to be understood?

I’d never heard the term ‘authorial reticence’ until last weekend, when I listened to author Michael Scott Clifton talking about it at a conference.

He spoke on the subject of ‘magical realism’ and dropped ‘authorial reticence’ on his audience. Intrigued by his description, I decided to blog about it.

Definition

Most often associated with magical realism, authorial reticence refers to a writer refraining from explanations about a fantastical setting or event. The story proceeds as if the astounding, magical thing happened every day. This encourages the reader to accept it and keep reading.

Antonyms

If that seems confusing, it might help to understand the term by exploring its extreme opposites. Think of a story where the author used an As-You-Know, Bob or an infodump to give a detailed description. Or consider a story where the author wrote out the moral. In each case, the writer took you by the hand and told you what to think.

Authorial reticence is the opposite of that.

Example

Authorial reticence can apply to sub-genres beyond magical realism. A classic example from science fiction occurred in Robert A. Heinlein’s novel Beyond This Horizon with this three-word sentence: “The door dilated.” No further explanation or description. Heinlein expected readers to form the mental picture, accept it, and read on.

Pros

Done well, this technique fosters engagement on the part of the reader. The author says, in an implicit way, “I trust you. If you’ll go along with me, I’ll entertain you without moralizing or boring you. No spoon-feeding, though. You may have to stretch your mind beyond normal credibility limits.”

Benefits include a shorter, tighter story that highlights action and drama. Readers get a sense of being welcomed into your story’s world, as if they’ve lived there for some time. Also, readers who feel trusted might well buy your other books.

Cons

Like any good thing, you can stretch authorial reticence too far. Throwing too many bizarre or fantastic elements in at once can confuse a reader, who now will be less likely to finish the story, or buy another.

Also, if you fail to establish authorial reticence in your writing style at the story’s outset, introducing it later can prove jarring.

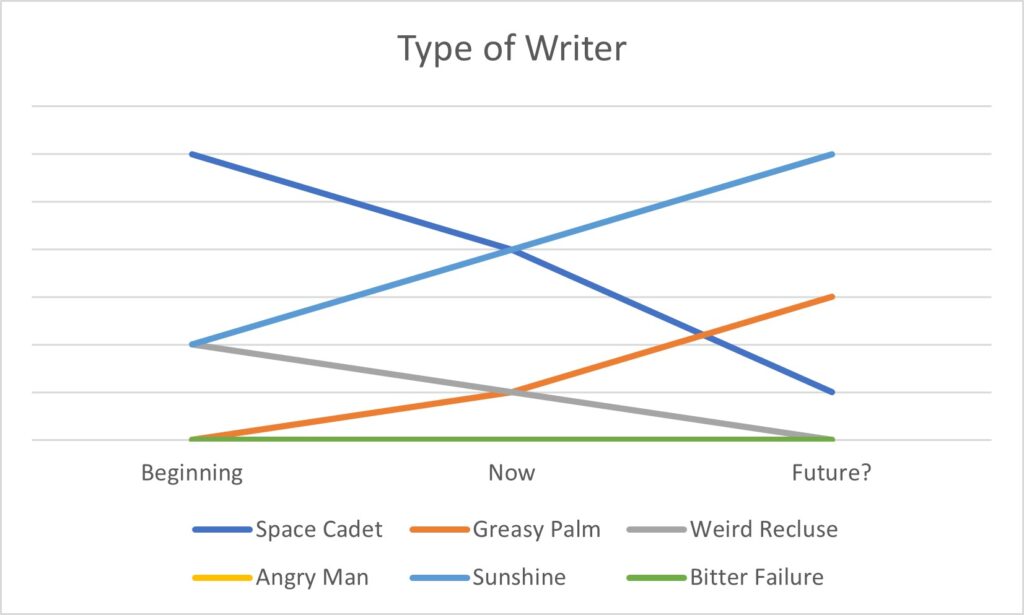

Reticence and Me

Given my engineering training, I suffer from a tendency to over-explain. I fear the reader might not form an accurate mental picture, or might reject my story element as too far-fetched. I’ll strive to resist this impulse. I’ll try to trust the reader’s imagination to fill in gaps.

From now on, if you’re looking for authorial reticence, you’re looking for—

Poseidon’s Scribe