My interviews tend to feature fiction writers, and an occasional poet. Today, to vary things up, I’m interviewing a nonfiction author. Daniel joined a writing critique group I’m in.

Daniel Johnston’s area of expertise is the business relationship between governments and oil companies. He’s traveled widely, worked for dozens of governments, and testified as an economics expert in 35 legal disputes. He teaches graduate level seminars to petroleum accountants. He’s written numerous books and articles, as you’ll read about in one of the questions below. In a less academic vein, he wrote the book Growing up Johnston, a compilation of stories and anecdotes about his wife and children extracted from a lifetime of journaling.

Here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Daniel Johnston: Early in my career I worked for a large consulting firm where publishing was the lifeblood of their marketing efforts. The old publish-or-perish trope applied there just as much as it did in the academic world. I also managed to develop a few analytical techniques that are now in common use in the industry and I wanted to get credit for them.

But, for me it was more than just career ambition. There was certainly the allure of getting published and I also felt somewhat compelled.

It is hard to say where that came from but I suspect it is just part of the human condition. I suppose some people get the urge and some may not. But even people who do not write or publish seem to appreciate the magic of it.

Now my inspiration and compulsion are what drive me most, not the commercial and marketing forces. This is especially true now that I am trying to capture and record many of my experiences over the past seventy years.

In addition to my personal experiences, I am trying to capture and breathe life into some of the old family stories that have passed down through the ages. Some of them have devolved into a single sentence or two such as the story of my children’s Great Great Great Grandfather John Gearhart. The family story that filtered down to my wife and me shortly after we were married was: “He was in the Civil War on the Union side. Fought at Shiloh and was wounded and crippled for the rest of his life.” My wife’s grandfather told me this and he remembered his grandfather. I have now extensively researched him and that battle and can show on a map roughly where he was (32nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry under General Hurlbut) half-hour by half-hour during that battle. At one point he was at the famous “Peach Orchard” where there was so much lead in the air, soldiers remembered and recorded that the falling peach blossoms looked like falling snow. I can’t help but imagine those beautiful peach blossoms and petals covering the bloody blue uniforms of the dead and wounded Union Soldiers lying on the ground in that orchard.

These are the kinds of things I want to write about now.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

D. J.: I was a voracious reader from early on in my existence reading such things as The Hardy Boys, A Wrinkle in Time, The Secret Garden, Little Women, etc. Fortunately, television in Wyoming in the 1950s was almost non-existent and reception was awful. Furthermore, our parents did not allow much television once it became so common in every household. We were not allowed to sit and stare at a TV. But, I loved reading anyway.

As I got older I preferred non-fiction history books such as Julius Caesar’s Conquest of Gaul or The Civil War and all kinds of biographies and autobiographies. In particular those about such characters as Benjamin Franklin, Golda Meir, Robert Rogers, Hernan Cortes, Alexander the Great, Chief Tecumseh, Hannibal, Cleopatra, George Custer, etc.

I also love historical novels like, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, Chang’s Wild Swans or James Michener’s works.

With respect to my career, starting in the early 1980s I read anything I could find that had to do with petrophysics, petroleum engineering, petroleum economics and finance. These subjects and my experiences are the foundations of the consulting practice I developed over the past forty years.

P.S.: Please give us a description of your book Growing up Johnston. What prompted you to write it?

D.J.: This book is a self-published memoir. My co-author, Julianna Johnston Ehlert, is our middle daughter. We only had fifty hard-cover copies of the book printed. If we want to print off a few more later it is easy and it is a miracle in this day-and-age to be able to do that! The book consists of over 340 pages of family anecdotes, photos, stories and journal entries. There is a chapter for each of our six children (three girls and three boys) and additional sections for stories that involved more than one child or my wife, Jill. Many of these memories are simply cute or sweet things the kids did or said or special moments in our lives.

For example, when our youngest daughter was around 4 years old, she asked me: “Daddy? Why is it that flapping works for birds but not for people?”

On another occasion we were out on a lake and my middle son said, “Hey Daddy! I saw a fish jump!”

“How big was it?” I asked.

He thought for a minute then said, “About the size of an octave on the piano!” All three of the boys play the piano and violin.

There are a lot of other events that are not so light hearted. In 1980 we had a still-born baby. I wrote about that pregnancy and that painful experience as well.

Everybody with children has experienced these sweet and powerful moments and that is what this book is all about—a record of those precious heart-warming/heart-breaking times in our lives and in the lives of our children.

P.S.: Tell us about your journaling habit. When did it start, and why do you do it? What do you write about?

D.J.: I started writing/recording in a journal shortly after I got married. In addition to recording the various nuggets and landmark events in our lives, I often took my journal on trips with me and there were always lots of things to write about. I also took our children with me on many business trips, sometimes just one child or my wife and sometimes a few kids or the whole family. My journals have been helpful for remembering times, places, people and details of some of the incidents and experiences I am trying to capture in my collection of short stories.

P.S.: You are likely the most widely-published author in the world on the subject of the business relationships between governments and oil companies. Please give us a brief listing of your major written works in this field.

D.J.: This is a pretty bold claim but I believe I am also the most widely quoted or cited author on this subject. Not only that, my second book, International Petroleum Fiscal Systems and Production Sharing Contracts, was essentially the first of its kind in the international petroleum industry.

By way of explanation, I got involved in the international oil industry at the end of the 1970s just as many governments were opening up to foreign investment in their petroleum sector. The World Bank was helping many developing nations craft petroleum laws and regulations and contract terms to enable them to establish business relationships with international oil companies. Because I worked for a consulting firm I worked with many different governments and companies. Most of my peers in the international sector worked for one or two companies in one or two countries. Their perspectives were much narrower than mine.

By the late 1980s I realized there were few people in the industry with the range and depth of experience and knowledge of the subject as I had. I recognized my opportunity and saw publishing as a way to stake my claim on this niche and advance my career.

I ultimately published five books through PennWell Books, three by the University of Dundee, Scotland, and one with the World Bank. I also published a large database on contractual/fiscal terms in various oil producing countries and I am currently working on a second edition to this database which stands at over 1,500 pages.

PennWell was the main publishing house in the petroleum industry during the1980s-2010s. PennWell also published the Oil & Gas Journal and Offshore Magazine, (now published by Endeavor Business Media). These were two of the main periodicals in the industry during most of that time.

I published a number of articles in their magazines before I wrote my first book for them, Oil Company Financial Analysis in Non-technical Language. This book did well due to the fact that it reached a broader audience than most of PennWell’s other, more focused, books. Their ‘non-technical series’ books were often their most popular.

I should point out that I had many huge panic attacks when I worked on that book and the next one. I would be overwhelmed by insecurity. What if I make a big mistake? What if people don’t like it? What if it is a failure? It could ruin my consulting practice. These attacks were brutal. It always took me a while to convince myself that I had a number of nuggets, even whole chapters in these books that were unique and would benefit people. I was right. My first book became required reading for candidates wanting to earn official certification as petroleum accountants. This was administered by the Institute of Petroleum Accounting and the Council of Petroleum Accountants Societies (COPAS).

As a result of this book, I was asked to write a column for the Petroleum Accounting and Financial Management Journal published by the Institute of Petroleum Accounting at the University of North Texas (UNT). I wrote my column for about ten years and taught annual seminars at UNT.

My next book (1994), International Petroleum Fiscal Systems and Production Sharing Contracts went viral. It has been translated into the Russian and Chinese languages as have most of my PennWell books. Both of these books stayed on PennWell’s bestseller list for over a dozen years. Inclusion on their bestseller list, I should point out, was based simply on gross revenues. The top 25 titles, in terms of gross revenues, are included on their bestseller list. I was their first author to have two books on their bestseller list at the same time.

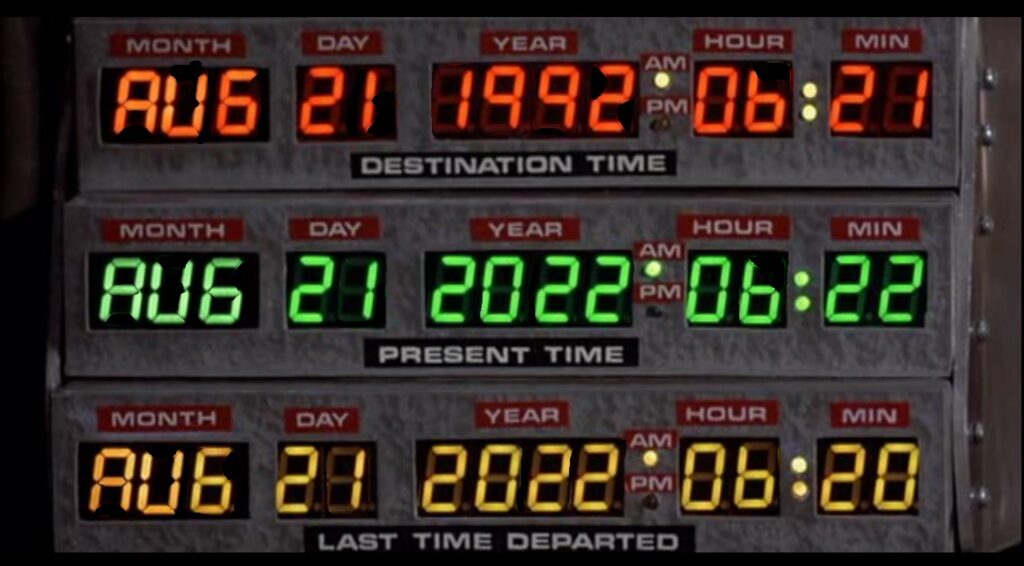

I published three other books for PennWell including a few other works. Of these, my favorite, is International Exploration Economics, Risk and Contract Analysis (2003). This has also been translated into Russian and Chinese. It makes a good companion book to my book on fiscal systems and production sharing contracts. My five PennWell books ranged from 100,000 to 150,000 words each. And, I might point out, the first few books were researched and written before the internet was born. I spent hours-on-end in libraries in Dallas and Dundee. Researching the old-fashioned way!

Two of my other favorite books were published by the University of Dundee in Scotland. These include: Economic Modeling and Risk Analysis Handbook (about 450 pages) and Maximum Efficient Production Rate (60 pages).

I taught there for over ten years. Each year I would go to Dundee and teach two one-week long seminars attended by both LLM students (Masters of Laws – postgraduate ) as well as industry people from around the world, such as accountants, financial people, managers, executives from both oil companies as well as governments. Because the subjects were still relatively new, and my books were so popular, my courses were heavily attended.

I taught my courses all over the world in both the public setting as well as in-house courses for oil companies as well as government agencies (national oil companies or oil ministries). During the next 25 years I averaged 10-15 overseas trips per year.

In 2007 two lawyers (Dr. Thomas Walde and Tim Martin) and I founded a new professional journal, the Journal of World Energy Law and Business (JWELB). It is published by the Oxford University Press (OUP) and the Association of International Energy Negotiators (AIEN). It is a refereed journal and has been a huge success. I have been the Vice Chairman of the Executive Committee since the inception of this journal.

Also, I have published over 100 articles, half of which have been in refereed publications. I have been cited over 1,250 times that I know of.

Knowing my subject thoroughly was one thing. My books launched me into the stratosphere.

P.S.: Your job has taken you to many countries. Do you plan to write about these experiences?

D.J.: Yes. I have been to places I never dreamed of or even heard of before. So, I have seen a lot of things that I believe people might find interesting or inspiring. I was raised in northern Wyoming along the eastern face of the Big Horn Mountains. To me it was a paradise. I never dreamed of traveling abroad. Nor was it an ambition of mine. My career, from 1980 onwards, changed all that, but I still see the magic, mystery and misery of our world from the perspective of a Wyoming native and proud American.

Traveling to the countries and regions where the oil industry was active was much more important when my career began. This is because communications were nothing like they are today. For example, in the late 1970s sometimes people had to fly from Jakarta to Singapore in order to make a phone call back to the United States. Back then we sent and received Telexes. Also, primitive computers and fax machines were just starting to enter the workplace in 1980. So, traveling was more common back then because we didn’t have ‘virtual’ capability such as Zoom or Webex.

As a result, I got to see a lot places and things that few of today’s generation in the petroleum industry will likely experience.

For example, around 1996 I was in New Delhi about to head home when I was contacted by a lawyer I knew in Singapore. He asked me to come to Singapore and meet with him so that we could go to Jakarta for an important meeting. So I joined him in Singapore, and as we settled into our seats on the flight to Jakarta he handed me a magazine and pointed to the picture on the cover. It was of a handsome young man about my age, Setaiwan Djodi. “This is who we are meeting with.” he said.

The magazine had an article about Djodi, a Javanese prince and famous musician. He was also, at that time, owner of Lamborghini, the famous Italian car company. The article also mentioned that Djodi had put on a concert and half a million people showed up. During lunch the day I met him I said, “I read this article that said half a million people came to your concert! That is fabulous.” He shook his head and smiled, “Oh no. It was only around 300,000.”

He had a potential business opportunity (petroleum) in Kazakhstan and wanted me to evaluate the situation. So, from Jakarta I went on to Kazakhstan and spent a wild week there traveling from Almaty to Autyrau on the north coast of the Caspian Sea. That trip was amazing and I hope to capture and preserve some of those stories.

I was also stranded in Lagos Nigeria for two extra weeks because of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Centers. That was a crazy time. In those days the Murtala Muhammed airport (Lagos) was considered the most dangerous airport in the world and it was shut down for international flights to the US and many other countries, thus the two-week delay. When I was finally able to fly out, I was instructed to arrive at the airport twelve hours early. I arrived thirteen hours early, just to be safe, and there was already a line. It was probably during one of my many trips to western Africa that I contracted malaria—another story.

As a result of my work and travels, I have seen a lot of this world in the past forty years and I am writing about those travels.

P.S.: What are the easiest, and the most difficult, aspects of writing for you?

D.J.: I have decided that writer’s block can be fatal. I have only barely survived a number of close calls. And, for me, panic attacks come without warning and are always fueled by insecurity, as I mentioned previously.

One of the biggest problems for me is to get things in the proper and logical sequence. This is true of both my technical/economic writing as well as my essays and short stories. This effort taxes every ounce of my powers of explanation but my technical books are much easier to write compared to writing a story or essay.

I have not yet tried to write fiction and tremble at the thought. However, to me thought of it fascinates me. I am not sure I have the talent or the ability to write fiction but I plan to try some day.

P.S.: I understand you’re a musician and gardener. Do these hobbies complement your writing or are they a relief from writing?

D.J.: There are a couple of short vignettes that are influenced by my modest musical background and love of classical music. I have already started work on two such stories. One deals with meeting a young woman named Tasmin Little—who, at the time, was solo violinist for the Brussels Symphony Orchestra playing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto. We spent three evenings together because of a chance encounter in Brussels. It is a simple sweet story but it adds a different flavor or dimension to my collection of experiences I am writing about.

Another minor story that involves classical music took place in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan on my first trip there. However, that is about all there is to the influence of my music on my writing so far.

With respect to gardening, I only have a couple of small stories, vignettes actually, that I hope to bring to life. One is a simple story that involves a metaphorical vine I came across in a Sumatran jungle. I have thought about it a lot since then. Sometimes it is the little things that touch our hearts.

P.S.: What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

D.J.: At the moment I am just finalizing and recovering from a project I had been working on for years. I provided expert witness testimony in an arbitration between a big oil company and a foreign government involving a $1.5 billion claim. I do a lot of this kind of work the last twenty years. These projects require a considerable amount of written testimony that must be carefully and meticulously crafted. This is because everything I write in an expert witness statement and every article or book I have ever written come under intense hostile scrutiny that culminates in various rebuttal statements from opposing experts and ultimately, oral cross examination—pure hell.

Other than my professional writing obligations, I am also working on a book of short stories (essays) about the experiences and subjects I mentioned above.

Also, in addition to my international travels, I am writing about some of my experiences growing up in Wyoming in the 1950s and 1960s, and being an identical twin. I am also working on some of the old family stories. For example, I have an ancestor who fought under Admiral Nelson in the Battle of the Nile and then was crippled with grape shot at Trafalgar. I want to bring that story to life—doing lots of research at the moment.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Daniel Johnston: If you feel you have a story in you—you do. It is there and only needs work and inspiration to give it life. With respect to the work I just mentioned it helps to have some writing skills.

Writer’s block, insecurity, panic attacks and self-doubt are part of the experience in my opinion. Perhaps it wouldn’t be such a grueling experience for me if I had studied writing instead of almost exclusively focusing on the physical sciences.

Fortunately, the wonderful part of writing is the editing process. With all of my manuscripts, books, articles and witness statements, I edit over and over and over. I will easily go through dozens of drafts for even small articles or stories.

With respect to writer’s block, when the frustration becomes overwhelming, take a day off. Or more. Do anything other than write or worry about writing. Sometimes the human mind does its best work when we are doing anything other than work.

Also, join a writer’s group. While I only have experience with the Fort Worth Writers group, it has been wonderful for me in many ways. Fascinating people. Fabulous learning opportunity. I love it.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thanks, Daniel. Readers who want to find out more about Daniel Johnston can check out his website.