Isn’t it fun when a fiction book includes a map? If you’re like me, you linger over the map longer than you do any other page of the story. A map draws you in and makes you feel like you’re there, like you could use it to navigate from any spot to any other. As you read the story, you keep referring to the map to pinpoint the current action.

Maps of Others’ Stories

Sarah Laskow wrote a marvelous post about maps associated with fiction. Her article includes maps from The Swiss Family Robinson by Johann David Wyss, Walden; or, Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau, Treasure Island, by Robert Louis Stevenson, and others. Laskow discusses the reasons fiction writers make maps and their delight in drawing them.

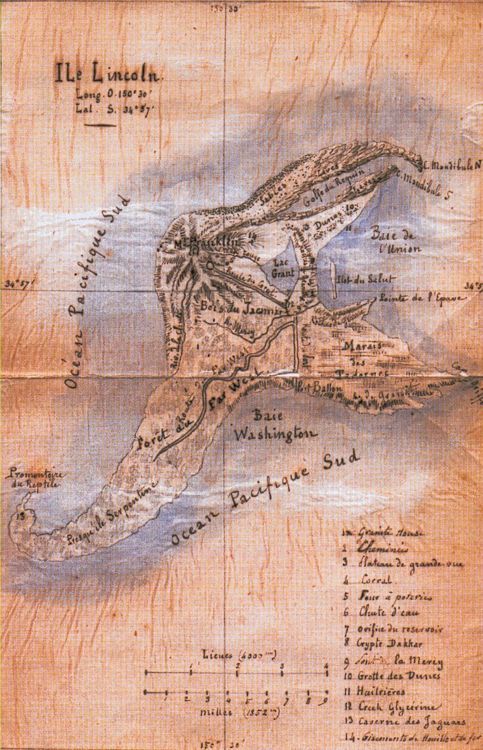

Lincoln Island

Readers of this blog know I adore Jules Verne, so I couldn’t resist mentioning the map of Lincoln Island included in his book, The Mysterious Island. His characters explored every extent of it, and named the significant features as well as the island itself. You can’t help but follow along with the castaways by flipping back to the map to see where they are.

Map of The Seastead Chronicles

While writing my book, The Seastead Chronicles, I made a map to keep things straight. However, I did not include that map in the book.

The stories in the book take place in our near future as people colonize the seas. As they’ve done on land, they carve out nations with borders, but call the oceanic countries “aquastates,” and people cluster in cities, called seasteads.

On my map, I refrained from noting seastead locations. Unlike cities on land, some seasteads can move, though others are anchored in place. One or more aquastates consist of a single, mobile seastead that travels the world (or at least, wherever it can get permission to go).

Problems with Mapping Aquastates

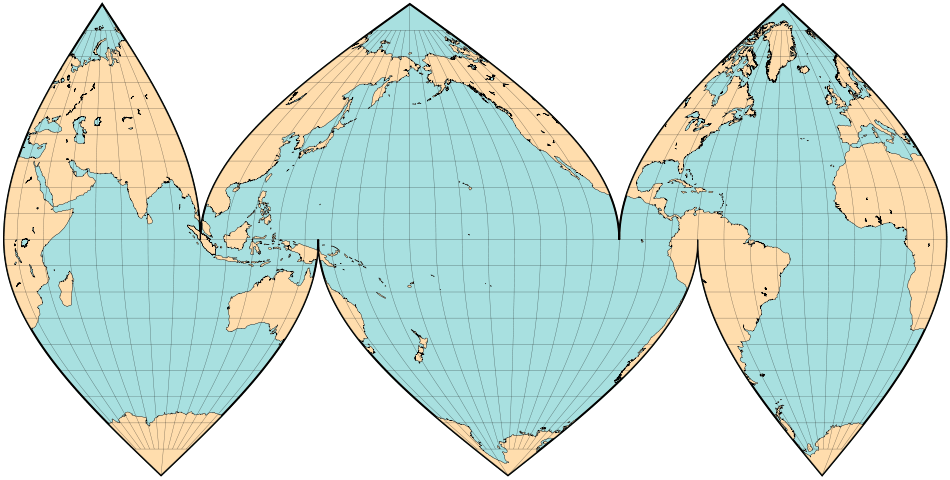

Borders between aquastates need not consist of lines marking vertical planes, as they do on land. In one case, a single aquastate overlaps another and their borders in that region cut horizontally, with a depth separation. Two-dimensional maps don’t show that situation well.

I faced another problem—map projections. Most world maps emphasize land, since that’s where people live…today. However, you can slice the orange other ways, to emphasize the oceans. Therefore, I based my aquastate map on what’s called the Interrupted Goode Homolosine Oceanic View. That map projection carves through land masses so you can focus on the water.

Another difficulty lay in the fact that The Seastead Chronicles spans a period of almost a century. No single map would suffice for that entire time, due to the varying number, shape, and area of aquastates over the decades. In the early years, people set up lone aquastates with no neighbors. Then the water got more crowded. As more people migrated to the oceans, some aquastates failed and collapsed while others grew and spread. Near the year 2100, I supposed, things might stabilize when the cost of war or legal disputes exceeded the benefit to be gained from additional territory.

Want to See It?

Are you curious about what my aquastate map looks like? I’m not ready to release it to readers yet, but I will sometime soon. Sorry about the cruel tease, but some things must wait until all is in readiness for—

Poseidon’s Scribe