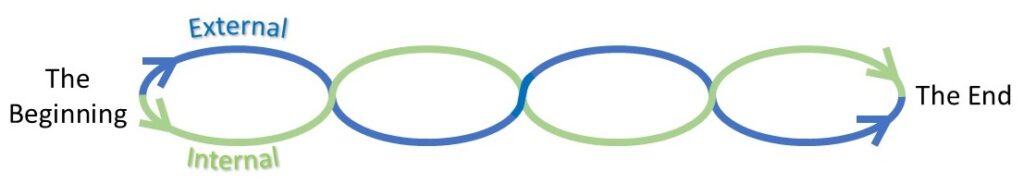

Often, the best stories show us two journeys. In one, the protagonist contends with an outside force, possibly another person, to confront and resolve a problem. We call that the plot. The other journey takes place within the protagonist’s mind and involves emotions, beliefs, personality, and, in the end, learning and change.

You’ll find a nice overview of this in editor and writing coach Ley Taylor Johnson’s post here and I encourage you to read it. My post emphasizes different points but (I hope) expresses the same overall view.

The 4 Aspects

Johnson says your main character should have a want, an obstacle, a need, and a flaw. She states them in that order since that’s the sequence for revealing them in the story.

The character wants something, and that strong desire provides motivation. However, the obstacle stands in the way. The obstacle could be a person, some aspect of the setting, or some other negative force. You should establish the want and the obstacle early.

Later, introduce the character’s need. The need is the reason for the want, and goes deeper than the want. The need is the underlying, emotional, psychological, or philosophical answer to the question, “why does the character want what she wants?” The character may be unaware of the need early on.

Most often, protagonists also suffer from a flaw. Like the need, the flaw resides within the character—a personality defect, a phobia, a suppressed memory, etc. As with the need, the character may be unaware of the flaw at the beginning, or might have grown accustomed to concealing it.

How the 4 Aspects Relate

The want and the need both propel the character forward. The obstacle and the flaw oppose that movement. The want and the obstacle are, most often, tangible and external to the character. The need, as mentioned before, explains the want—providing the underlying reason for it. The want may not last to the end, or may change. The character may abandon the want. But the need usually does not change, though it may be satisfied at the end.

How do the obstacle and the flaw relate? The obstacle, whether wittingly or not, preys on the flaw, targets and exploits it. While the obstacle appears early, the flaw may lurk unseen until late, though the writer might provide hints of the flaw all along. In the end the character must confront both the obstacle and the flaw, and resolve, in some way, the problems they create.

The Journeys

In the external journey, the character pursues the want but is stymied by the obstacle. When asked what a book is about, a reader often answers with this external journey, the plot.

The internal journey takes place in a different realm, one of doubts, fears, bouts of sadness, joys, thoughts, prejudices, mindsets, etc. Within her mind, the character journeys first to understand the need and eventually to attain it, despite being opposed by the flaw.

The Journeys Intersect

Much of the time, the external journey moves forward through action and dialogue, leaving only brief moments for a character’s fleeting thoughts. A good writer won’t let the internal journey slow the pace of the most intense scenes of the external journey.

Use the down-times between high-tension scenes to allow the internal journey to come to the fore. During these interludes, the character takes time for reflections, deeper thoughts, realizations, revelations, and learning—progress on the internal journey.

In the end, both journeys reach completion. The external journey features the character confronting and overcoming the obstacle to either attain the want, or to achieve a larger goal. The internal journey shows the character confronting and overcoming the flaw to satisfy the need.

Perhaps two other journeys end here, as well. You’ve finished reading this blogpost, and the writing has been completed by—

Poseidon’s Scribe