If you’d like your fiction to sell well, wouldn’t it be beneficial if readers found your stories easy to read?

Not all writers see it that way. Some authors of the world’s great classic literature made it tough on their readers, but their books still became bestsellers. Obviously, readability alone doesn’t determine great writing.

For the most part, the factors of great writing remain intangible, but you can measure readability. Many word processor software packages calculate the ‘Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease’ score, as well as the ‘Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level,’ both standard measures of readability. The higher the Reading Ease score and the lower the Grade Level, the more readable your story.

Journalist Shane Snow inspired me to think along these lines with this wonderful blogpost. He did a lot of research obtaining Flesch-Kincaid data on many great fiction authors, and graphed it all.

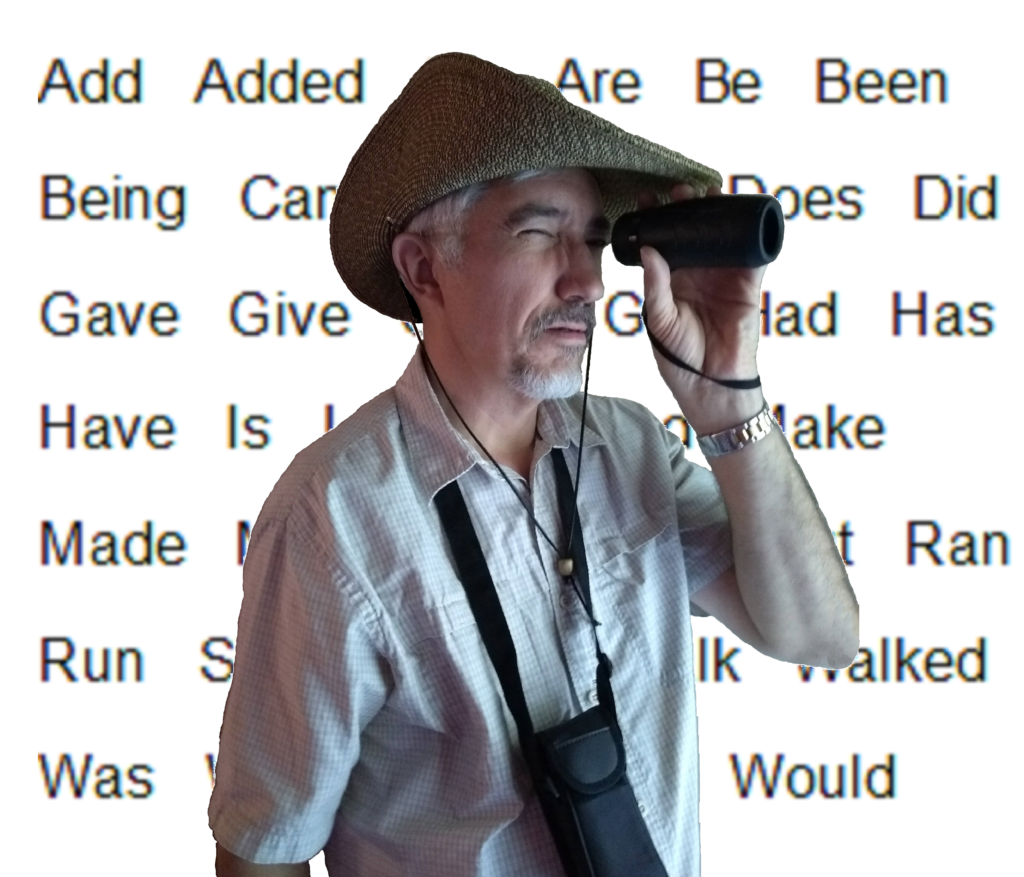

That made me wonder how I measured up. I obtained the data on my ten most recently published stories. Listed from least readable to most readable, here they are:

| Story | Flesch-Kincaid Reading Ease | Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level | Genre | Year Written |

| “The Steam Elephant” | 69.0 | 6.8 | Alt Hist | 2006 |

| “Target Practice” | 69.3 | 6.5 | Scifi | 1999 |

| “The Unparalleled Attempt to Rescue One Hans Pfaall” | 69.8 | 6.5 | Alt Hist | 2011 |

| “Reconnaissance Mission” | 71.4 | 6.2 | Alt Hist | 2019 |

| “Ripper’s Ring” | 72.2 | 6.4 | Alt Hist | 2015 |

| “Moonset” | 74.8 | 5.3 | Horror | 2018 |

| “A Clouded Affair” | 75.9 | 5.5 | Scifi | 2014 |

| “The Cats of Nerio-3” | 76.3 | 5.1 | Scifi | 2016 |

| “After the Martians” | 78.3 | 5.1 | Scifi | 2015 |

| “Instability” | 79.1 | 4.8 | Alt Hist | 2017 |

Not too many obvious patterns there. My alternate history stories tend toward less readability than my straight science fiction, but not always. To some degree, I’ve improved readability with the passing years, but there’s some scatter in that, too.

When I average the F-K Grade Level of these stories, I get 5.82. According to one of the charts in Shane Snow’s post, that puts me around the readability level of Hunter S. Thompson, and between early J.K. Rowling and Stephen King. Not bad company.

If my stories don’t sell as well as theirs, it only proves that, as I mentioned above, readability alone doesn’t make for great writing.

What if it did? Could you write in a way that maximizes your Flesch-Kincaid readability score? The Wikipedia entry gives the formula. It’s very simple. Just take your average number of words per sentence and the average number of syllables per word, and the rest is math.

To make readers struggle, use long words and long sentences. To make your writing more readable, do the opposite.

To make your stories irresistible and widely sold…ah, that’s the magic formula I’d really like to know. That equation—whatever it is—might contain readability as one factor, but also many others. Ernest Hemingway earned a F-K Grade Level of just over 4, and Michael Crichton earned one a little under 9.

Shane Snow makes the point that a lower F-K Grade Level allows you to reach a larger potential audience for your stories. However, he cites two other factors that help determine whether your writing will gain traction and catch on. I’ll discuss my take on those in a future blogpost.

Although readability alone won’t determine whether your stories sell in the marketplace, consider this: if all other factors rated the same between two stories, wouldn’t you prefer the more readable one? I suspect you would, and so would—

Poseidon’s Scribe