The English language cries out for more verbs.

Verbs strengthen sentences and energize them with action. Nouns, adjectives, adverbs, prepositions and the rest just sit there, doing nothing, until the verb wakes them up and sets them into motion.

Yet, for all their importance, verbs constitute only about one seventh of all English words. We need more of them.

I know, I know. Writers, especially advertisers, are creating more verbs all the time. They’re ‘verbing’ nouns as fast as they can. Not fast enough, in my view.

In the meantime, we must work with what we have. Still, beginning writers tend to choose the worst and weakest verbs from among the few available. Why? Because it’s easier.

But that easy path results in flat sentences, drab paragraphs, and uninspiring prose. It’s time you hunted down those weak verbs and replaced them with strong ones to make your sentences sturdy, your paragraphs powerful, your tales tantalizing.

Join me now on a hunt for weak verbs. After I give you a few pointers, you’re free to hunt on your own, through the thorny thickets of your own manuscripts.

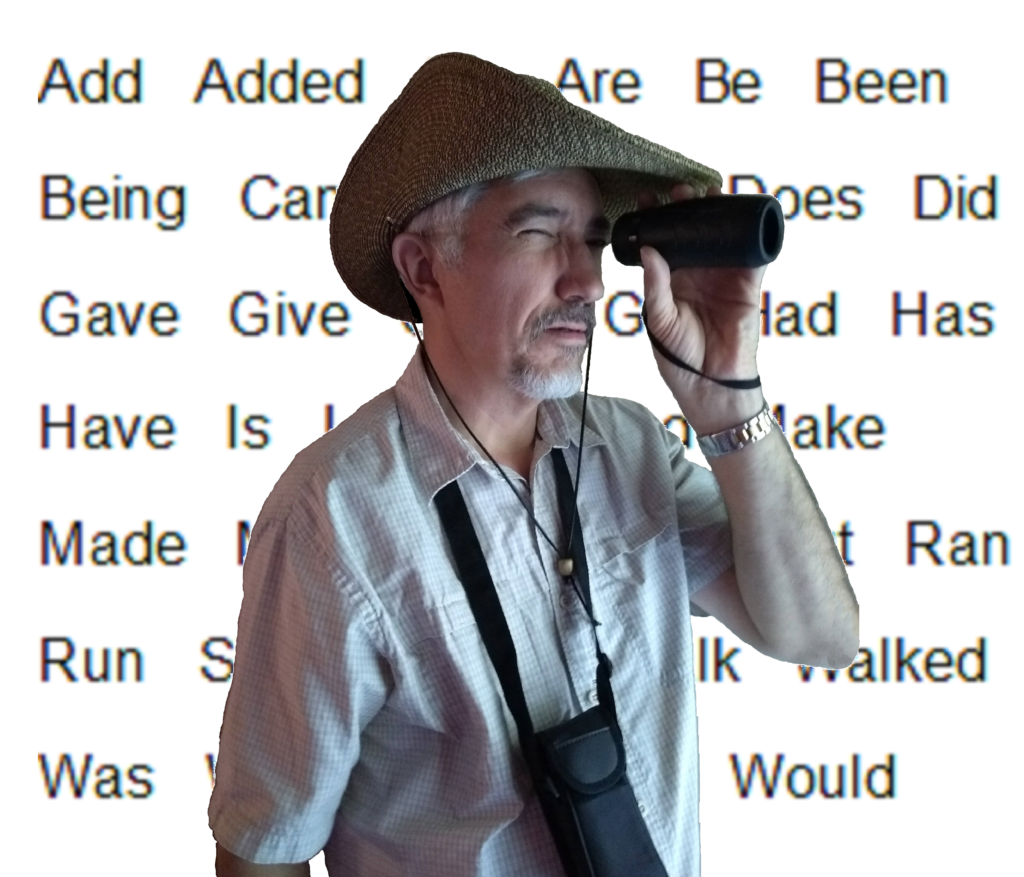

I classify the so-called “state-of-being” verb as the weakest species of verbs. These simply equate a noun to an adjective or adverb. They include the following: Am, Are, Be, Been, Being, Can, Could, Do, Does, Did, Had, Has, Have, Is, May, Might, Must, Shall, Should, Was, Were, Will, and Would.

As an example, consider this sentence: “She was on a hunt for weak verbs.” It conveys meaning, but packs no punch. Better to write: “She hunted for weak verbs.” That draws us in more, forces us to look over her shoulder as she seeks her game.

Sometimes you can’t avoid using these state-of-being verbs, but don’t load a paragraph down with them, and try to think of good alternatives first.

The next species of weak verbs isn’t as bad as state-of-being verbs, but is worth hunting to near extinction. I’m talking about abstract verbs like add, give, go, look, make, put, run, and walk, along with the various tenses of these verbs. They tell us something, but just the bare minimum. They beg for an adverb to spice them up.

Rather than, “She looked carefully in every corner of her manuscript for weak verbs,” consider “She peered into (or examined) every corner…”

Again, circumstances may force you to use an abstract verb now and then, but strive to minimize those times.

Note that my list of abstract verbs excluded ‘say/says/said.’ Yes, ‘said’ and its forms belong in the list of abstract verbs, and tell us in a bland way that a speaker uttered audible words. However, they represent an exception. While hunting, we pass them by.

Why? Because nobody sees that word—it’s invisible. Readers skip right over it. Use it as often as you like. No reader will tire of reading ‘said.’

That verb’s mild nature might tempt you into modifying it with an adverb. Don’t. You’ll end up with a “Tom Swifty.” Also, suppress your urge to substitute different synonyms for ‘said,’ such as avowed, declared, professed, spoke, or stated. That comes across to readers like you’re overusing your Thesaurus.

I hereby pronounce you qualified to hunt for weak verbs on your own. Good luck! To get you started, you might try seeking out a few weak verbs in this blogpost, left there as practice for you, by—

Poseidon’s Scribe