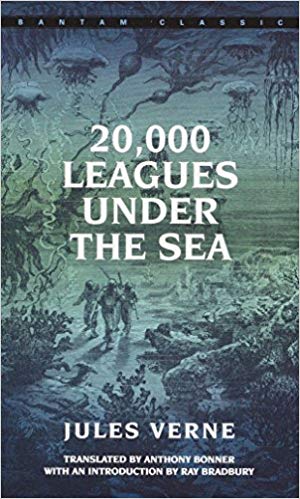

Did one of Jules Verne’s female fans inspire history’s most famous undersea adventure novel, a work that includes not a single female character?

First, readers of my posts will note I’ve been writing a lot about 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea lately. That’s because I’ve teamed up with editor par excellence Kelly A. Harmon of Pole to Pole Publishing to develop 20,000 Leagues Remembered, an anthology filled with short stories paying tribute to Verne’s submarine masterpiece. It’s scheduled to launch on June 20, 2020, the sesquicentennial of the famous novel. Write your own story now, and submit to this site.

Let’s set the scene. It’s 1865, early in Jules Verne’s career. He has contracted with the famous editor Pierre-Jules Hetzel, and two of his novels have already achieved fame in Paris and across France: Five Weeks in a Balloon (1863) and Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864). Another novel, From the Earth to the Moon, will soon be released.

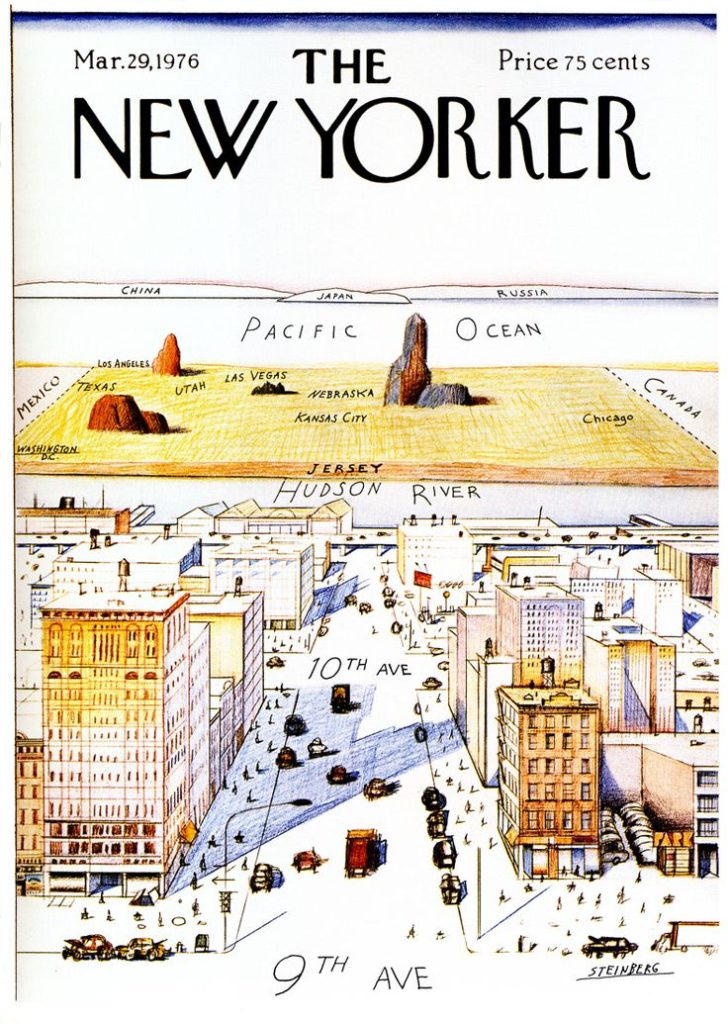

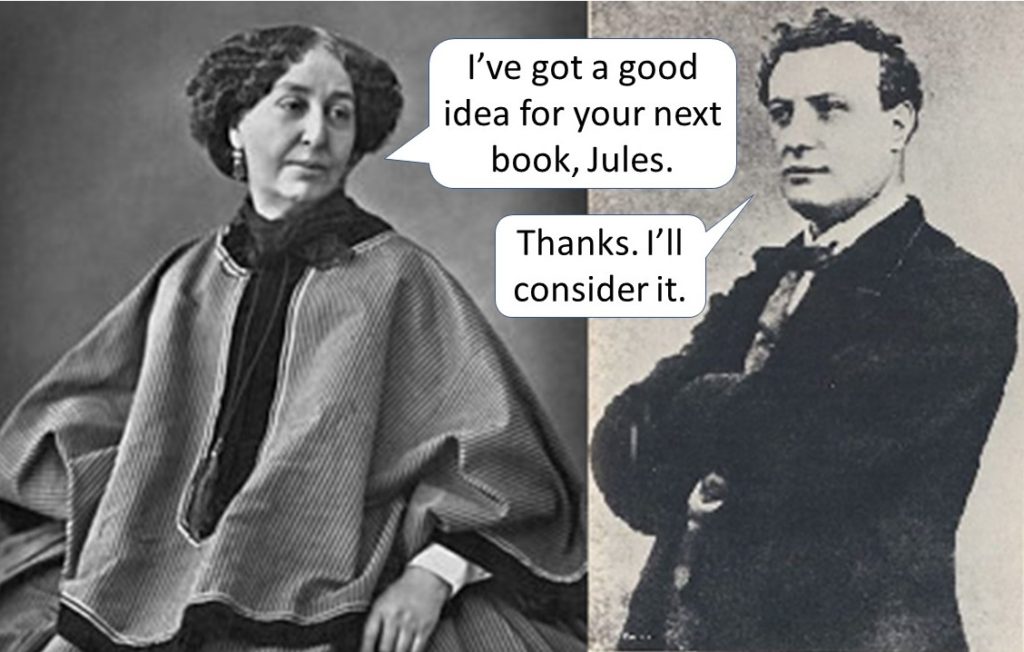

Sometime during that year, Verne receives a letter from a woman. After she praises both Five Weeks and Journey, she writes “Soon I hope you’ll take us into the ocean depths, your characters traveling in diving equipment perfected by your science and your imagination.”

Within a few years after that, Verne sails on the ship Great Eastern to visit America, and acquires his own sailboat, the Saint-Michel. Writing aboard his boat, he boasts to his publisher that he’s writing a new novel with an oceanic setting unlike anything written before. It will be “superb, yes superb!” By March 1869, the first chapters of 20,000 Leagues begin appearing in Hetzel’s magazine.

What can we conclude? Did Verne get the idea for 20,000 Leagues from a fan letter? Had she not written to him, would Verne have begun such a novel?

First, who was this mysterious woman? She was none other than George Sand, the pen name of Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin. By 1865, Sand had achieved fame in her own right, having written numerous popular novels and plays. Her publisher was the same Pierre-Jules Hetzel who published Verne’s works. When she wrote to Verne, she would have been about 61, and he about 37.

No doubt Sand had noted Verne’s talent and observed the success of what would come to be known as Verne’s Voyages Extraordinaires. She had a keen sense of what would catch on with the French reading audience of the time.

So, was Sand’s letter truly the spark that led to Captain Nemo and the Nautilus? We may never know for sure. I’ve seen no evidence that Verne wrote back to Sand or admitted to anyone that the idea had originated with her.

We know, too, that Verne visited the Exposition Universelle (World’s Fair) in Paris in 1867 and saw a model of a primitive (and unsuccessful) submarine, Plongeur. He also saw demonstrations of electrical apparatus there. Could these exhibits have inspired 20,000 Leagues instead?

It’s impossible to say with any certainty whether George Sand provided the true impetus for Verne’s novel. It’s fun—and a bit ironic—to think she did, for there are only a few minor mentions of women in the novel.

Still, in case George Sand did inspire Verne to write 20,000 Leagues, she deserves this sincere thank-you, sent back through time, from—

Poseidon’s Scribe