‘Tis the season for giving and receiving, so I thought I’d discuss critiques of fiction manuscripts. Last time I did so, I said I’d let you know how to give and receive critiques. My  experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

experience is based solely on twenty years of being in small, amateur, face-to-face critique groups; not writing workshops, classes, or online critique groups; so the following advice is tuned to that sort of critique.

First of all, to give the critique, keep the following points in mind:

- Read the submitted manuscript straight through once, and just note where you were “thrown out of the story” for some reason. Jot down why and come back to those points later.

- Re-read the manuscript again. You could mark some of the grammar or spelling problems, but don’t concentrate on those. The author wants you to find the bigger stuff.

- Where there are stand-out positives (“Eyeball kicks” in TCL parlance) note those and praise the author. The word critique should not have solely negative connotations. A positive comment from you could keep the author from later deleting a really good description, metaphor, or turn of phrase.

- Be clear and specific in the comments you write; avoid ambiguity.

- Look for the following story elements and comment if they’re not present or they’re weak:

1. Strong opening or hook

2. Compelling, multi-dimensional, non-stereotypical protagonist with human flaws

3. A problem or conflict for the protagonist to resolve

4. Worthy secondary characters, different from the protagonist, who do not steal the show

5. Vivid settings, not overly described

6. Consistent and appropriate point of view

7. Appropriate dialogue that moves the plot and breaks up narration

8. Narration that shows and doesn’t tell.

9. A plot that builds in a logical way, events stemming from actions that stem from understandable motivations

10. A story structure complete with Aristotle’s Prostasis, Epitasis, and Catastrophe (beginning, middle, and end)

11. Appeals to all five senses

12. Active sentence structure, using passive only when appropriate

13. Appropriate symbolism, metaphors, similes

14. A building of tension as the protagonist’s situation worsens, followed by brief relaxing of tension before building again

15. An appropriate resolution of the conflict, without deus ex machina, resulting from the striving of the protagonist, and indicative of a change in the protagonist

- If your group shares comments verbally, do so in a helpful, humble way.

You think all that sounds pretty difficult? Ha! It’s much harder to receive a critique. When doing so, here are the considerations:

- Submit your work early enough to allow sufficient time for thorough critiques. Be considerate of your group members’ time.

- While being critiqued, sit there and take it. No comments. No defensiveness. Just listen to the honest comments of a person who not only represents many potential readers, but who wants you to get published.

So, when it comes to critiques, is it better to give than to receive? In contrast to most gifts, it’s harder to receive them, but it’s still a toss-up which is better overall. But perhaps both are just a bit easier for you to deal with now, thanks to this post by—

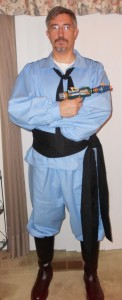

Poseidon’s Scribe

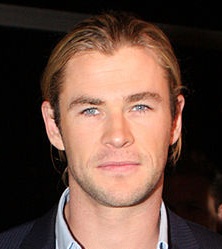

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense.

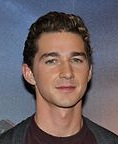

Federmann could be played well by actor Chris Hemsworth. He’d have to speak English with a German accent, but doesn’t have to do it well, since it’s a comedy. Count Federmann is a brooding character, angry at and jealous of Baron Münchhausen. The Count is intelligent, determined, and optimistic, but lacks sense. The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility.

The Count has a young French servant named Fidèle, and I’ll select Shia LaBeouf for that role. Mr. LaBeouf would have to speak English with a French accent, but not an especially good one. Fidèle is full of life, but has the sense to fear danger, though he’s always respectful of nobility. Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “

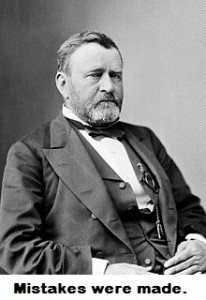

Robin Williams. I need an older character of plain appearance who’s able to speak English with a German accent and captivate an audience with his words alone. Robin Williams played the part of the King of the Moon in the 1988 Movie “ Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).

Among the worst passive sentences ever written is “Mistakes were made.” Politicians since Ulysses S. Grant have used that one to acknowledge a problem but to hide the responsible party from blame. However, the press and the public are on to that tactic, and would pounce on any official who uttered it (after laughing out loud).