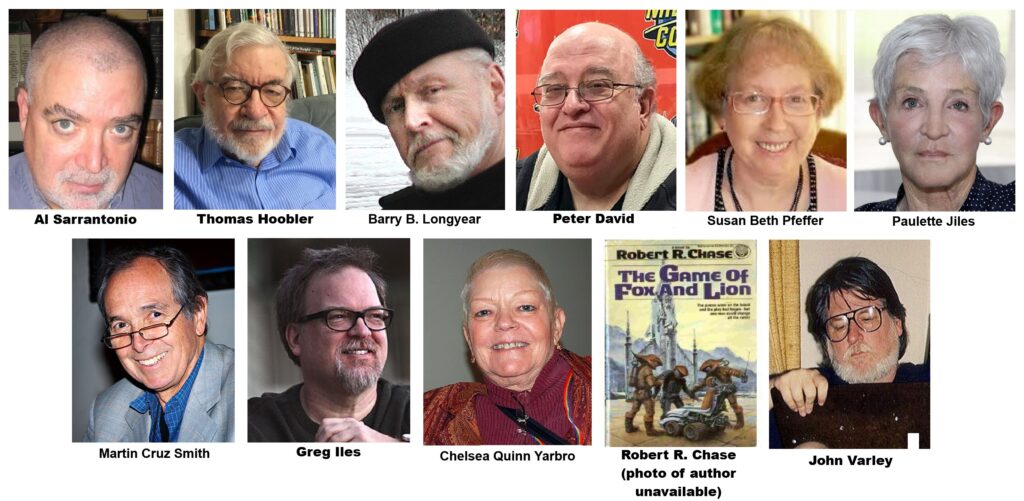

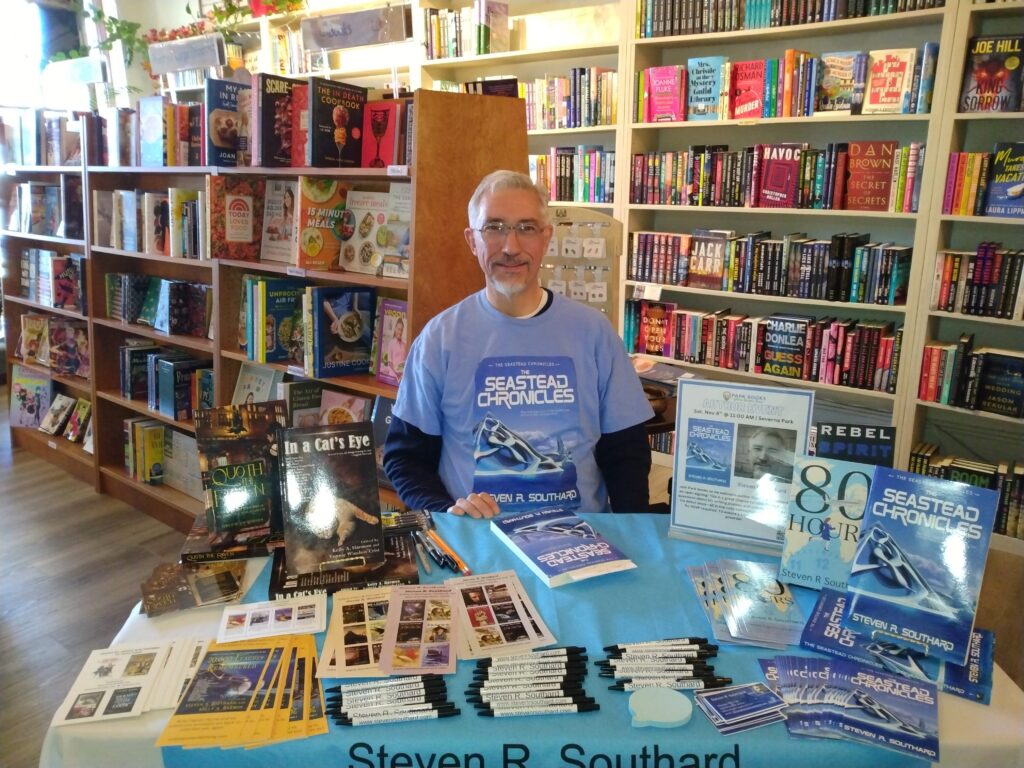

As fortune would have it, I shared a book signing table with Darby Harn, one of the guests of honor at ICON 49.5 earlier this month. Beginners like me can learn about selling books from watching a more experienced writer like Darby. In the interview below, you’ll read how his writing career stalled at one point, but he persevered. From that experience, he offers two profound words of advice—two—for aspiring authors.

Bio

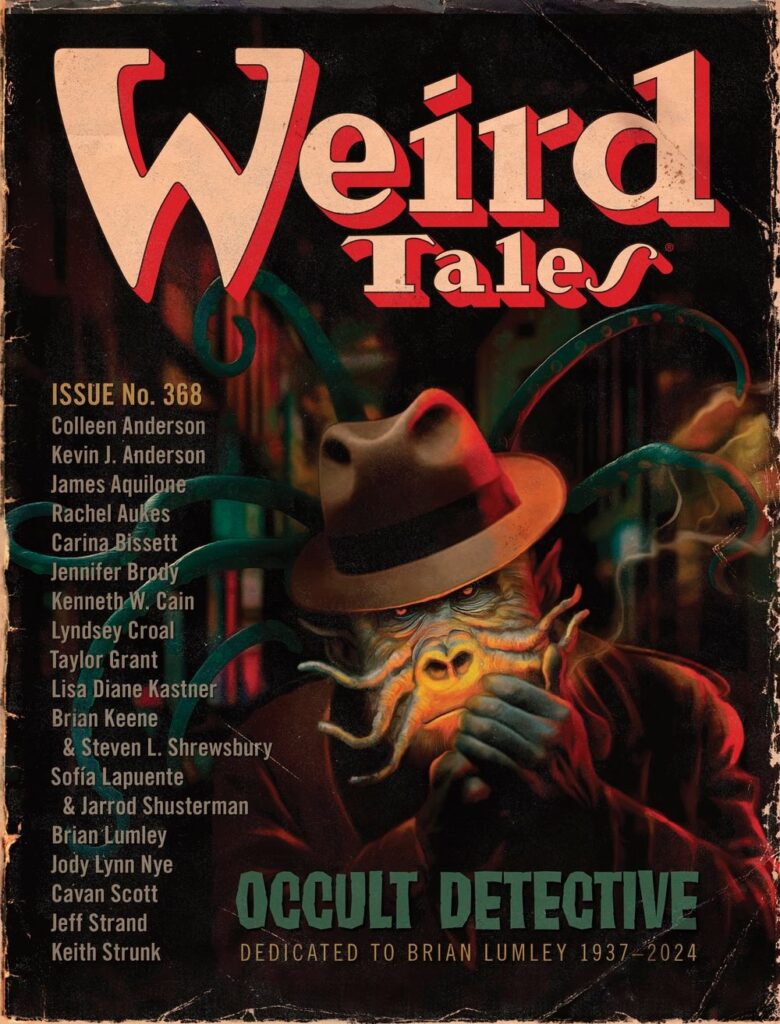

Darby Harn is the best-selling, critically acclaimed author of Dead Malls, Stargun Messenger, a Self Published Science Fiction Contest Quarterfinalist, and Ever The Hero, which Publisher’s Weekly called an “entertaining debut that uses superpowers as a metaphor to delve into class politics in an alternate America.” His fiction appears in Strange Horizons, Interzone, Fantasy Magazine, and more. He is a panelist, moderator, and programmer, designing a variety of content modules for conventions, including his One Hour Short Story Workshop, featured at several major cons. He graduated from the University of Iowa and is an alum of the Irish Writing Program at Trinity College in Dublin, Ireland.

Interview

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Darby Harn: I don’t remember not writing. I was writing and drawing little comics at the dining room table when I was three. I just always wanted to tell stories and share them.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

D.H.: Star Wars is probably the single biggest influence in terms of what it did to my toddler brain but also how it inspired me to explore myth, anthropology, and the literature that inspired it. I don’t know about favorite books. How do you choose? My favorite writers include Seamus Heaney, Virginia Woolf, Chris Claremont, Michael Cunningham, Kelly Link, and so many more.

P.S.: In your book Stargun Messenger, your protagonist sounds fascinating. Tell us about her.

D.H.: Astra Idari is an android bounty hunter who pursues thieves of starship fuel. When Idari discovers that the fuel comes from the blood of living stars, her entire moral universe is upended.

P.S.: As a frequent book reviewer for FanFiAddict, please tell us about that site and why you review books by others.

D.H.: FanFiAddict is a great resource and community for sci-fi and fantasy reviews from trad to indie. My mom died in September, and I am really slacking in my contributions. I owe some people a lot, especially my thanks.

P.S.: Our sympathies about the death of your mom. Since shopping malls are dying around the country, Dead Malls seems an apropos title. Give us the premise of this novel. Is it really a choose-your-own adventure?

D.H.: CYOA is an element of the book, and it creeps up on you, getting super twisty, and I hope super fun. The book is about Sam, a security guard at a dying mall just trying to get through their shift. One night, they discover an intruder in the mall who claims to be the only survivor of a nuclear war that happened in 1983. Then things get weird.

P.S.: Sounds fascinating! It appears you got your start writing short stories and moved to novels. If true, why the change, and if not, tell us about your experiences with the various forms (lengths) of fiction and how your fiction has evolved.

D.H.: I was always primarily a long-form storyteller, but I came up while short stories were still the primary route into traditional publishing. You sell a few stories, get noticed hopefully, and get a book deal. That’s what happened to me in the early 2000s, though it got very messy after that.

I sold my first novel in 2006, and it was 2011 before I realized it was never going to come out. The entire experience derailed my life and career. I was so stymied I didn’t finish a novel between 2007 and 2015. For a long time, I didn’t think I would.

P.S.: Sorry you had that experience, but glad you wrote your way out of it. Your book, Ever the Hero, begins the Eververse series. Please tell us about this introductory book and premise, and world(s) of Eververse.

D.H.: Ever The Hero is what happens when you don’t pay your superhero bill. In this world, if you can’t afford them, they don’t help. Kit Baldwin is a regular person trying to get through the day. She gets powers, wants to help others, but it’s illegal; they make you pay. This leads to a huge conflict over who owes what to whom.

P.S.: Is there a common attribute that ties your fiction together (genre, character types, settings, themes) or are you a more eclectic author?

D.H.: I think the defining aspect of my writing is its elasticity. I’m a mashup of a lot of different interests and inspirations, ranging from Marvel Comics to Irish poetry. That results in genre fiction, which tends toward the poetic and the literary.

P.S.: We’ll get to your Ireland connection in a moment. First, you’re not serious about writing a short story in an hour, are you? Tell us about your workshop.

D.H.: The most common question I get is ‘Where do I start?’ After that, it’s usually ‘How do I get unstuck?’ My One-Hour Short Story Workshop is a way for aspiring writers to kickstart their stories by focusing on the beginning, middle, and end of a short story, having them write to a prompt, share, and hopefully leave the experience with the foundations of a story. It’s a joy to watch people create in real-time. I’ve conducted the workshop at major cons, including Twin Cities Con, GalaxyCon, and others.

P.S.: You seem to prefer places beginning with “I”—Iowa and Ireland. Did your time in the Emerald Isle inspire your book A Country of Eternal Night?

D.H.: A Country of Eternal Light doesn’t exist without Ireland. While I was a student at Trinity College in Dublin, I visited the Aran Islands. Like so many others, I was transfixed with the place. I always wanted to go back. Cut to twelve years later or so, my dad had died, I’m not writing anything, and I’m miserable in my very well-paying job. So, in 2014, I quit, moved to Ireland, and returned to the islands. The experience unlocked what became Country, and my career today.

P.S.: It sounds like Ireland inspired more than just one book! What is your current work in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about it?

D.H.: I have a few things going on right now, but progress is pretty slow. Next up on deck is the third book in the Stargun Messenger trilogy, followed by Eververse Book 5.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring authors?

Darby Harn: Never quit.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thank you, Darby. The most succinct writing advice ever given.

Web Presence

Readers can discover more about Darby Harn on his website, and at Goodreads, Amazon, Facebook, and Instagram.