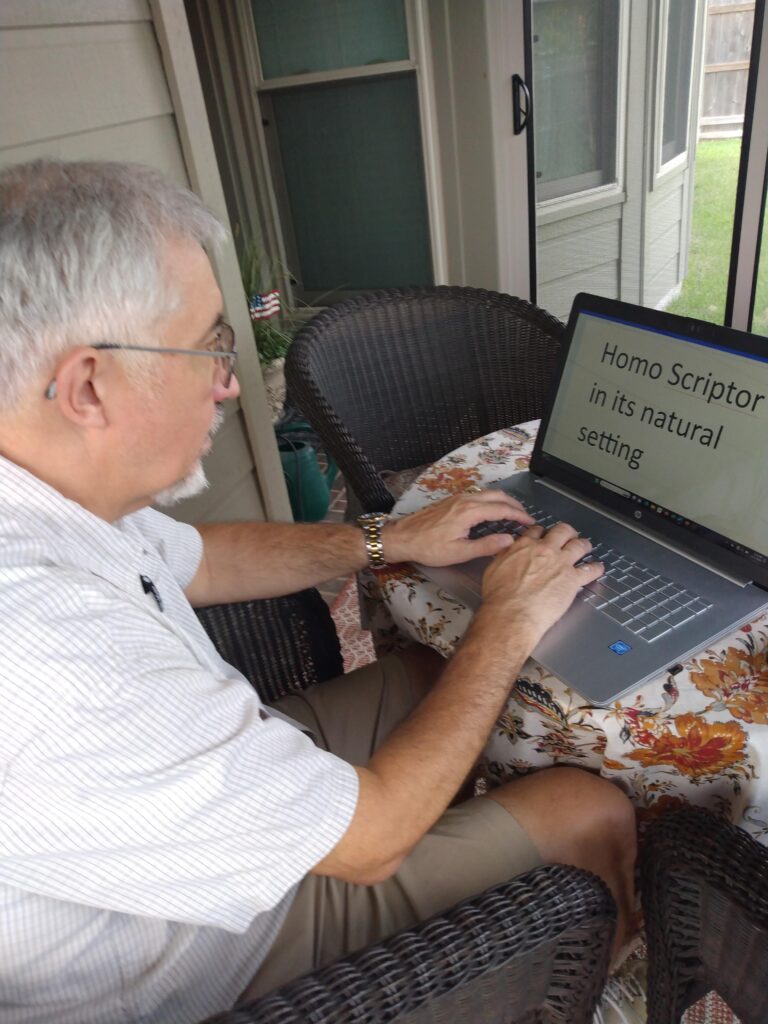

You’ve thought about writing fiction. However, the moment you did, your inner critic bashed the notion and rolled out ten reasons you shouldn’t. Your inner critic was wrong. Today, I’ll bust those myths about writing fiction.

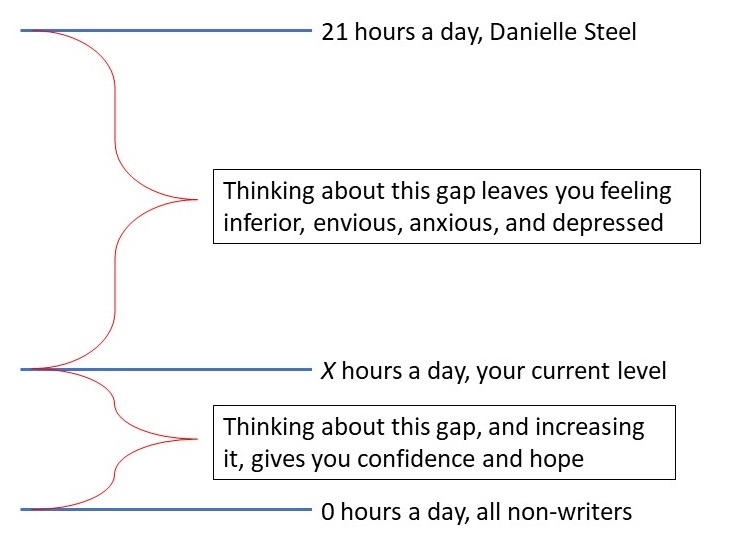

10. I don’t have time to write.

In one sense, your inner critic was right about that. You don’t have time to write. Neither do I. No writer does. We all make time for it. We deliberately carve out time out of our day for writing, no matter how brief it may be.

9. I could never write as well as [insert your favorite author’s name].

Since you’ve never tried, how would you know? Even if it’s true, who cares? You’re aiming at the wrong target. Adjust your aim to write as well as you can.

8. I’ve led a dull life. If I write what I know, it’ll be a dull book.

If you had suffered a troubled past, that would give you much to write (with authority) about. But you’ll have to admit—your past wasn’t all dull. You experienced fear, pain, triumph, loss, and love. Remember those emotions and write about them. More important than writing what you know is writing what you feel.

7. I don’t know all the English rules well enough.

This ain’t English class. Editors and publishers won’t quiz you on the difference between a reflexive pronoun and a ditransitive verb. They’d trade a hundred grammar experts and another hundred spelling bee champions for one great storyteller. You can learn the rules of English faster and easier than you can learn the craft of weaving a compelling tale.

6. I’ve heard you need a muse. I don’t have one.

Forget the muse. It’s a metaphor for creativity. I’ll give you two ways to increase your creativity, and each beats waiting around for an ancient Greek goddess to whisper in your ear. (1) Practice 20-solution brainstorming, where you write down 20 solutions to a problem without regard to workability or practicality. Don’t stop until you reach 20. (2) Channel your 5-year-old former self. You were creative then.

5. I don’t know the ‘author tricks.’

Of course you don’t. That’s because all the highest-paid authors belong to a secret society, and you haven’t been initiated. Wait, no. There’s no such secret society and no author tricks. What worked for others won’t work for you, and vice versa. You’ll have to figure out your own tricks, like everyone else. Many authors have written how-to-write books, but there’s no sure-fire formula in this biz.

4. Writers are introverts and I’m an extrovert.

You may be extroverted, but writers come in all personality types. If the thought of writing alone bothers you, collaborate with another writer. Or attend a party after each writing session, to get back in your comfort zone.

3. I’ll get stuck and suffer from writer’s block.

Maybe. Probably. It never lasts long. Whatever inner force compels you to write will insist you resume at some point. If you listen to that voice inside, it will help you get unstuck.

2. All the best stories have already been written.

Maybe that’s true. So what? More stories get published now than ever before, so that excuse doesn’t seem to be stopping other writers. One thing’s for sure—your best story hasn’t been written, and you’re the only one who can do it.

And the number one myth about writing is—

1. I won’t make any money from writing.

Hmm. What a coincidence. All the highest paid authors in history likely had that same thought at some point. It might end up being true in your case, but you can’t know that yet. Most writers keep their day job until their writing income grows to a point that they feel comfortable quitting that job. Maybe you’ll end up loving writing so much that you won’t care so much about the money.

There. I’ve busted the top ten myths about writing fiction. What’s your next excuse? Whatever it is will soon get demolished by the sledge hammer belonging to—

Poseidon’s Scribe