Welcome to Poseidon’s Pub! Come on in. There’s an empty stool here at the bar. What can I get you?

Bars, taverns, pubs, taprooms, watering holes, alehouses, saloons, cantinas, grogshops, dives, and joints serve as frequent settings in fiction. Little wonder. They’re common settings in real life, too.

In fiction, though, they perform a different function than in real life. Let’s examine that subject.

To the reader, it should seem that your character enters the bar for any of the reasons real people do. These include (1) to have a good time in a congenial, social environment, (2) to forget or escape troubles, (3) being dragged in reluctantly by friends, (4) to meet someone the character already knows, and (5) to meet someone the character would like to know.

In real life, that’s about all there is to know. We enter for one or more of those reasons, or some similar reason, and we either succeed or fail, but we leave with less money, fewer fine motor skills, and fewer brain cells.

However, things are different in fiction. The overall point of the fictional bar scene is to advance the plot, add depth to a character, or both. A fictional bar scene might accomplish one or more of the following functions:

- Show a character’s behavior in a relaxed, non-work or non-family setting. This allows the writer to display new facets of the character.

- Reveal more of a character’s thoughts, feelings, and background. This scene might serve as a way to unveil the tale’s backstory.

- Reduce tension after an action scene. It may allow both reader and character a chance to catch their breaths and reflect on what just happened before.

- Make use of reduced inhibitions. The effect of alcohol on any of your characters might allow them to admit a truth they’ve been hiding, or propose an idea that’s just crazy enough to work.

- Gain information or ideas from another character. This can be from a direct conversation with that character, or could be gleaned through intentional or accidental eavesdropping on another conversation.

- Form, strengthen, or end a relationship with another character.

- Show a conflict between two characters. A writer can illustrate this with a heated conversation, a game like pool or darts, or the classic bar fight.

As with any scene, you’ll need some description of the setting, the layout and ambiance of your fictional bar. Your readers already know what a bar looks like, so choose enough details to sketch a mental picture in the reader’s mind, but trust the reader to fill in the rest. You’ll want the overall mood of the bar to reflect your character’s mood, or that of your story at that point.

Bar scenes in fiction have become so typical, so stereotypical, that you’ll need to find a way to make yours unique, atypical in some way.

If your character returns to the bar later in your story, ensure something has changed. Most likely your character has learned something along the way. Seen through your wiser character’s eyes, perhaps the bar looks different now, or the character notices things missed on the earlier visit. Or maybe the bar looks so much the same that your character reflects on its sameness.

I grew up reading science fiction, and those tales contain plenty of bar scenes, from Isaac Asimov’s ‘Union Club,’ to Arthur C. Clarke’s ‘The White Hart,’ to Larry Nivens’ ‘Draco Tavern.’ No doubt you pictured some favorite bar—real or fictional—as you read this blogpost, so there’s no point in my listing hundreds of examples from written or cinematic fiction.

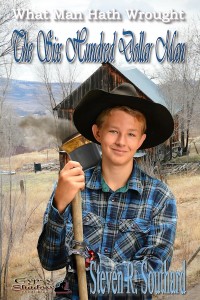

My story, “The Six Hundred Dollar Man,” contains a bar scene in ‘Shingle & Locke’s Saloon.’ It serves the purpose of relating the first amazing stunt of the Six Hundred Dollar Man and of raising ethical questions about whether it’s right to give a man steam-powered legs and one-mechanical arm.

Sorry! Closing time, folks. Settle up your tabs and have someone get you home in safety. And don’t forget to tip your favorite bartender—

Poseidon’s Scribe