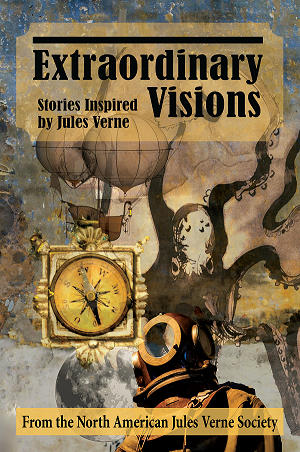

For today’s author interview, I flew to Australia and sat down with… No, actually, I did this one all by email. Mike Adamson has separate stories in both 20,000 Leagues Remembered and in Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne.

Mike Adamson holds a Doctoral degree from Flinders University of South Australia. After early aspirations in art and writing, Mike secured qualifications in both marine biology and archaeology. Mike was a university educator from 2006 to 2018, has worked in the replication of convincing ancient fossils, is a passionate photographer, master-level hobbyist, and journalist for international magazines. Short fiction sales include to Metastellar, Strand Magazine, Little Blue Marble, Abyss and Apex, Daily Science Fiction, Compelling Science Fiction and Nature Futures. Mike has placed stories on well over two hundred occasions to date, totaling some 1.1 million words. Mike has completed his first Sherlock Holmes novel with Belanger Books, and has appeared in translation in European magazines. You can catch up with his journey at his blog ‘The View From the Keyboard.’

Here’s the interview:

Poseidon’s Scribe: How did you get started writing? What prompted you?

Mike Adamson: I think I must have been a latent storyteller from a very young age. I would cite exposure to classic Star Trek and of course the many worlds of British TV producer Gerry Anderson as strong inspirations, as was 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, my favorite story at age 5. It was also the classic Space Race era, those of my age grew up with the fact that space had become accessible, and this spurred many a reverie for inquiring minds. I remember being in school around age 5 or 6 and being given the exercise of drawing a picture and writing a caption, and what I produced was two pages of writing with a small drawing at the bottom of each—about a voyage to the Moon as I recall. I remember my teachers being in deep discussion over it! Then, not many years later, I would look at a blank writing pad and experience an almost indescribable urge to fill those lines with text, to create something wonderful, to tell a great story but also invent something, a world, a time that doesn’t exist, in the process. I must have been born for speculative writing!

As a kid I worked on a series of adventures about space travelers who fell through a time warp into an age of cavemen and dinosaurs, then tried a couple of more ambitious projects about space exploration and the colonization of the Moon. Around age twelve I learned to type and hammered away at an epic, if somewhat naive, science fiction novel, without actually completing it. I finished my first original science fiction novel at age sixteen: having digested the works of E E Smith and reveled in the early Star Wars and Galactica era, there was no surprise in it being space opera on a grand scale. In my teens I wrote rafts of fan fiction, which was a good exercise in learning to produce feature-length texts.

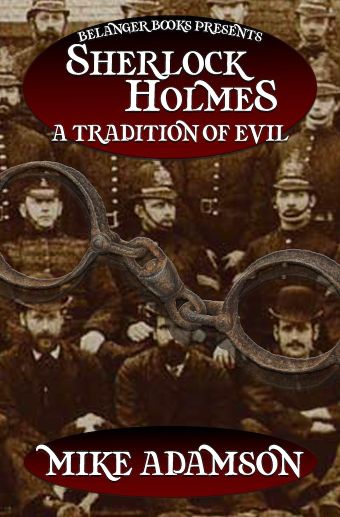

P.S.: Very exciting that your novel, Sherlock Holmes: A Tradition of Evil, will be coming out later this year. The video trailer is captivating. Tell us about the novel.

M.A.: I’ve been writing Sherlock Holmes short stories since 2019 and have had excellent success in placing them, so for my debut novel I wanted to do something on a big scale—real stakes for the characters and for society in general. I also wanted to explore Holmes earlier in his career than we usually encounter him, allowing the story to be foundational to the awe in which he is held in later years. I set the piece in the December of 1885, early enough for many Police to still regard him as a meddling amateur, which provides for some interesting frictions.

The story concerns government and law enforcement itself, and I needed the character of Mycroft to make the logic work. The story introducing Mycroft, “The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter,” is one of those which contains no date reference, but, luckily, some scholars place the story as early as 1885, and I chose to run with this. I have the full line-up of supporting characters—Inspectors Lestrade, Gregson and Bradtsreet, Mrs Hudson, Wiggins and the Irregulars, plus genuine historic figures, such as the Home Secretary, and the Commissioners of the City and Metropolitan Police Forces.

I wanted to draw the reader into the case at a very visceral level, so after gathering the threads together in the traditional way, I opted for a blow-by-blow account of the closing drama, a night of tension and action as Holmes and Watson pursue their man across the city. I’m hoping readers appreciate this approach and find the finale to be real edge-of-the-seat stuff.

Recently I was invited to work up a second novel, and am perusing my notes for the best storyline for a further outing.

P.S.: Speaking of Sherlock Holmes, that novel’s not your only story involving the iconic sleuth. What others have you had published, and how does your Holmes deviate, if at all, from Doyle’s original characterization?

M.A.: As I mentioned above, I’ve been writing Sherlock Holmes for the last four years, and currently have some twenty-two stories complete, around 220,000 words worth (with notes for a great many more). I began with a cross-over between Holmes and my own Victorian detective character, Inspector George Trevelyan (created in collaboration with my sister, Jen Downes, a very fine writer who has twice appeared in Analog, and with whom I’ll be sharing a table of contents next year in Sunshine Superhighway: Solar Sailings, from Jay Henge Publishing).

The Trevelyan stories are classic mystery with a supernatural edge, which contrasts with the Holmesian canon in which the supernatural is more or less “handled with tongs.” Having already completed a couple of Trevelyan adventures, I eased into Holmes by presenting him with a case that would not resolve without acknowledging a supernatural element, which he of course cannot do. He consults with Trevelyan to get to the bottom of it.

This piece, “The Misadventure of the Perspicacious Waif,” was accepted for Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine by the late Marvin Nathan Kaye in 2019, then switched to Weird Tales, from the same publishing stable, as he felt the readers of SHMM would not appreciate a piece which deviated from canon in recognizing a supernatural reality. That was fine with me, as it got me a berth in that grand old magazine of the strange! Unfortunately, after Marvin passed away, I’ve not been able to establish contact with the new editor, and the piece is in limbo—recorded by me as a pro-level placement but out there in some realm between the worlds. The stated theme for the next issue of Weird Tales is occult detectives, so I should have a fair shot, given that the story both fits the theme and has already been tacitly picked up. All I can do is watch like a hawk for the magazine reopening to submissions (which, on their random schedule, could be anytime) and re-pitch the piece to the new editor. Fingers crossed…

Since then I’ve written new adventures for the great detective across the period 1881 to (so far) 1916, with only a handful of unpublished pieces in hand at any one time. They’ve appeared in Sherlock Holmes Mystery Magazine (two acceptances, neither of which has appeared in print yet), Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine (Sherlock Holmes tribute issue Jan/Feb 2021), Strand Magazine (two placements, both now published, the second of which was actually solicited) and a total to date of eleven anthologies from Belanger Books. I’m enjoying being a Holmesian very much, am continuing to write and to expand my publishing venues.

My Holmes is essentially canonical, though some might say they find him less caustic than the original. However, I group my material in ways that agree or disagree with Doyle’s approach—for instance, I probably have an anthology coming along in the next year or two, which will consist of purely canonical tales, but a later volume might collect those with supernatural or otherwise strange themes, under the title “The Dark Holmes.”

All my stories follow a chronology which compliments the original canon, filling in the spaces between the classic stories (an approach I’m sure many have followed previously), so, regardless of the nature or classification of the tales, they can be read in order from the earliest to the last, with the novel(s) forming part of that collective arc.

P.S.: Who are some of your influences? What are a few of your favorite books?

M.A.: It’s difficult to say! My early influences included Clarke, Asimov, E E Smith and Heinlein, and in the fantasy vein Robert E Howard was the fascination of my youth, plus of course Burroughs. Later on I discovered Clarke Ashton Smith’s classic tales of cosmic horror, and finally devoured H P Lovecraft’s complete works. I read the entire Sherlock Holmes canon several years ago, of course, and have long enjoyed Jules Verne and H G Wells. Being a classics fan is an obvious benefit for writing in the public domain franchises, but leaves one rather out of touch with where the fields are at this point. (This also goes for writing “voice,” as there are times I find myself automatically composing in 19th Century expression, and have to wrench narratives back into contemporary “sound!”)

Among moderns, I would say Greg Bear has been a distinct influence—Eon in particular, whose imagery and concepts remain vivid to me. I would also cite the great Australian science fiction author Terry Dowling, whose saga of future Australia, the massive “Rhynosseros” arc, made a huge and lasting impression on me when I read the stories in paperback many years ago. His world-building still leaves me breathless, and the range and depth of his stories is epic. The late Jack Vance, a personal friend of Terry Dowling, is another whose world-building is legendary, and (as with Clarke Ashton Smith’s writing) lets one submerge in a cocoon of sensory stimulus that, I feel, modern stripped-to-the-bone writing hands away in the name of pace. Frankly, to me this is an unfortunate bargain in the name of attention-spans truncated by the speed of modern information access. No wonder I’m often accused of being heavy on the exposition…

From an early age I also considered myself an artist, so it’s natural that artistic influences should have impressed themselves strongly. Some artists shaped my view of both science fiction and fantasy from a young age: Chris Foss, the “Dean of Science Fiction Illustration” as he has been called, whose signature airbrush art remains the gold standard, tops the list for me, plus others from the British industry from the ’70s onward—the late Peter Elson, Angus McKie, Tim White and more. The great Bruce Pennington, whose distinctive non-airbrush style was like a signature for the New English Library range of the ’70s—I find his work strongly evocative and suggestive of story elements to this day. In the fantasy field, the late, great Frank Frazetta is the leading influence, along with Boris & Bell. Also past comics greats have played their part in shaping the color, texture and scope of my visualizations—Mike Noble, John Buscema, Don Lawrence, and so many others.

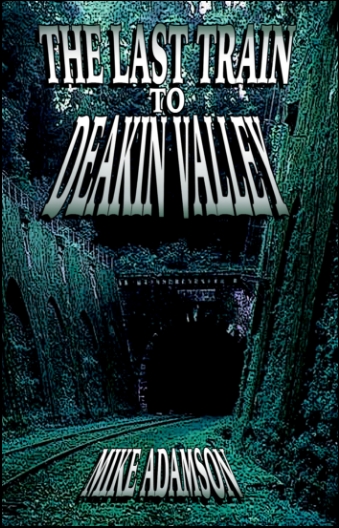

P.S.: Your first stand-alone, single-author publication was The Last Train to Deakin Valley. What is that novella about?

M.A.: Deakin Valley is a railway ghost story set in the Peak District of Derbyshire, England. Railways have an undying appeal all their own, but in the country where they were invented they also have the longest history. Britain’s rail map has changed often, with many old lines disappearing. Much of Britain’s railway engineering and architecture, its bridges and stations, is of Victorian vintage and it can be rather creepy when you encounter infrastructure long out of use. On the domestic rail network in my home town of Adelaide, South Australia, there are such features—disused stations, boarded-up tunnels, dismantled bridges—and observing those from passing trains got me thinking. A torn-up spur-line might once have led somewhere important, perhaps with a secret, something dark… And the story flowed from there.

I matched up a commercial photojournalist with a disaster a hundred years ago and gave him a mystery to chase, then threw in magic and a deep sense of existential dread that might reasonably dwell in a land so ancient, redolent with the fury and suffering of battles long gone by. I focused it all in a fatal attraction to solve the mystery—learn the truth, but die in the attempt? It was a lot of fun to write, and I have a second outing for the same characters in notes.

P.S.: Is it true you’ve made over 3000 story submissions in 88 months? On average, that’s more than a submission each day. Tell us about the importance of such persistence in the journey to publication, and about how you manage to write and submit so much.

M.A.: Persistence is everything! Well, not everything of course, it assumes you’ve mastered your craft and are submitting good ideas, well-written and edited. But when it comes to marketing, persistence, and a sense of self worth, are paramount. In the early days I took feedback from editors as an important guideline, but it occurred to me that it would be impossible to accommodate every opinion received in terms of reworking. When the same story was rejected by two different markets for precisely opposite reasons it became clear that editorial opinion is entirely flexible and random, and that rewriting to accommodate any one opinion may in fact be installing the very reason for the next rejection. This is not an easy situation, and now I look for commonality of reaction. If I get the same reaction from more than one market then it carries weight and is worth a rewrite. Otherwise, I simply persist in submission in the belief that sooner or later any particular story will cross the desks of first readers and editors who see my point and appreciate my telling, and this seems to hold true quite often. An early story one market considered unpublishable was later picked up by an another and printed with bare-minimum edits, which rather makes my case.

Yes, I recently passed three thousand submissions since I began to keep records at the beginning of 2016. I had four placements in the previous few years which convinced me that I could do this, and a few test submissions late in 2015 to get the hang of online engines like Moksha, but they don’t feature in my official list. My record for submissions is ten in one day, and for rejections, six. It’s a high-volume situation and is essentially a seven-day-a-week job, in which I check emails four times a day, and do most of my redirection of rejections each morning. Writing falls usually in the afternoon, though if I have the bit in my teeth on a new project I may do some composition at any available time.

Ideas flow at different rates, and my total number of new stories per year has been falling. In 2017 I churned out 62 pieces, a figure I have never approached since. I tend to write to prompts now, and could as easily be working on a flash as a novelette. I have sometimes written two flash pieces in one day. I have files of story ideas going back years and when I’m at a loss for an inspiration I look back over notes to see if anything grabs me. It’s a little mechanistic in that sense, but one must treat writing as a job, and producing new material is very important, given the generally low pay rates for reprints. That said, I have had a reprint or two which actually earned more than the original placement, so go figure!

P.S.: You’ve written a number of stories in a series you call Tales of the Middle Stars. What ties that series together? Which stories are published, and what are your plans for the series?

M.A.: Tales of the Middle Stars is an arc against a common background of the exploration and settlement of the stellar neighborhood in the centuries ahead. It describes a period of human colonial expansion and peaceful coexistence with several alien races. The basic idea postulates that current work on FTL flight by spacial warping pays off and that by the early 23rd Century our first vessels of exploration are examining the nearby stars. The discovery of planets requiring only minimal terraforming spurs a wave of colonization that extends into the 26th Century and beyond. The “Near Heavens” was the navigator’s name for the region closest to Earth, settled first, and the “Middle Stars” is the next region, beyond which of course lies the “Deep Sky.” I got the nomenclature from a starmap used as an on-set prop for the original Alien movie in the late Seventies, which was titled “The Middle Heavens.” That always stuck in my mind, and adapted easily.

The first story I placed, back in 2016, “Lo, These Many Gods,” in SQ Mag #28, was a Middle Stars piece, and since then I have completed fifty-five more, with thirty-nine published to date. My chapbook The Salamandrion, in the “Short Reads” series from Black Hare Press, is also a Middle Stars outing—actually the third story I wrote. Others have appeared in venues as varied as Andromeda Spaceways (twice), Stupefying Stories (forthcoming), Spring Into SciFi, Shelter of Daylight, Etherea, Phantaxis, and a host of anthologies.

The series begins early in the 23rd Century, when, in my timeline, Earth has turned the corner from absolute climate catastrophe and has been resettled from a chain of space cities. Most of the 22nd Century was occupied with global terraforming measures to turn back from that nadir, but during this time the FTL project matured on drawing boards out at the cities. The era of stellar exploration ushered in a whole new identity for humankind as not simply spacefarers, but members of a community of races, and all that that implies.

I have, or will have, stories ranging from those early voyages over a period of some three hundred years, with the densest accumulation to date ranging between AD 2480 or so to 2510. Between 2496 and 2501 humanity is embroiled in its first alien war, whose effects are felt over the following generations. And in the decade after that, a new and terrifying presence begins to be sensed among the worlds of the Middle Stars…

I would estimate there are a couple of dozen stories to go to fill in the chronology, sometimes revisiting characters, often moving among familiar worlds, and there will always be the opportunity for new outings in future. My hope is to collect the stories into anthologies with a publisher at some point, but what form that would take is as yet an open question. There are likely enough stories for four or five volumes, and the intention is to move into novels in due course, beginning with an epic answering the question of that “terrifying presence.” It’s a matter of finding the right publisher to take on such a project, and do it justice—this might be a project to undertake in cooperation with an agent. Until then, I’ll continue to produce the material for the short story market.

P.S.: A few of your stories involve climate change and take place in a post-habitable Earth. Tell us about these stories, and do you plan to write more in that vein?

M.A.: The climate crisis has been at the back of the scientific mind since I was a child—acid rain had already signaled that industry could affect nature, for instance. I remember a story in Science Fiction Monthly, in 1974, “Dancing in the Hour of Not-Quite-Rain,” in which people sheltered from acid rain in bunkers, and, finding they were over the maximum safe occupancy, threw out an old man, to burn, because it was his generation that allowed industry to break the world… Fifty years later, the problems are more fundamental, and industrial bloody-mindedness and a lack of political will smacking of universal corruption continue to drive us toward catastrophe.

This came to shape my thinking about the next centuries, and what unfolded was a narrative line which always featured the climate crisis in the background, regardless of the foreground characters or events. The remainder of the 21st Century, in this timeline, features worsening climate effects until, about 80 years from now, the planet becomes untenable for higher life forms. I pray this will never happen—but it makes for a good story! The “Post-Habitable Earth” tales occupy the 22nd Century and follow a number of scientists in their efforts to address the crisis, working from a chain of space cities at the L5 position, built in the later part of the current century by industrialists seeking a lifeboat from their own mess.

A number of stories look at what life has become for those left behind in underground redoubts and habitat cities (for instance “Rats,” which appeared in Andromeda Spaceways #76, October, 2019), how some genetically engineered themselves to live in the new environment, while other pieces look at the great project to restore the old climate, to cool the planet and reseed life, rebuilding the ecosystem from the ground up. “Flight of the Storm God” looks at that reseeding enterprise, and appeared in the Flame Tree collection Endless Apocalypse (March, 2018), then subsequently on the Little Blue Marble website, and was featured in their 2021 annual print collection.

The initiative turns the clock back to a planet cool enough and with enough oxygen to support higher life by the last decades of the 22nd Century—maybe too compressed a timeline, I admit, but I didn’t want to be unpalatably pessimistic in how long I extended the planet’s agony. And, with resettlement and recreation of the world from its own ashes, as it were, the stage is set for the Middle Stars stories to follow on.

Stories in this arc have appeared in Ecotastrophe II, Little Blue Marble, Compelling Science Fiction, Andromeda Spaceways and others; one was a finalist in the 2021 Gravity Awards. I have several more to write, bringing the “Post-Habitable Earth” arc up to book length, which obviously invites a collection under one cover at some point.

In this way, viewed at a global level, a great many of my science fiction stories form a contiguous series from the present day to some five centuries in the future. Many years ago I had a vision of an artbook chronicling the history of the next thousand years, and while that project never developed, thematic material of the sort it might have contained certainly has evolved in literary form.

P.S.: Your story, “The Silent Agenda,” appears in the 20,000 Leagues Remembered anthology. To most people, a contract discussion about translating novels wouldn’t seem interesting enough to write about, yet you turned that into a dramatic story. What prompted that story?

M.A.: Back in the 1980s I came cross Walter James Miller’s 1976 fresh translation of 20,000 Leagues, but the volume was packed away and forgotten until comparatively recently. I studied with interest his extensive introductory essay, both on Verne’s life and his treatment at the hands of translators. In the jacket blurb he described Lewis Page Mercier’s 1871 translation as a “literary hatchet job.” The revelation that as much as 23% of the original French novel had been excised I found both outrageous (for obvious reasons) and intriguing, as it meant there was actually much more to be enjoyed than I’d ever read before!

Mercier removed maritime and scientific material, references to French scientists, and indeed scrambled some of Verne’s technical material, so that Verne was dismissed by later English-speaking critics as not in fact knowing his own subject, when the errors were entirely in translation. In 1874 the American translator Edward Roth made the same observations (while unfortunately also perpetuating the problem by taking the extreme liberty of adding scenes in his own versions of some works!) This is blatant enough, but given Mercier’s other cuts I found myself wondering, as Roth had, if Mercier was not deliberately undermining Verne’s credibility. Indeed, it’s contrary to the translator’s role as the invisible intermediary (Mercier is not usually even given a credit in standard English editions), and of a scope which to me suggests a specific policy direction which could only have come from the publisher.

The political motivations behind these cuts run rather deep—specific mention of Nemo’s revolutionary inclinations, for instance. We knew he supported anti-establishmental activities, even the Ward Lock 1964 illustrated children’s edition features Nemo delivering gold to fund such groups. I found it highly significant that Verne’s intentions were interfered with. The cuts largely muzzled his political statement, shifting emphasis firmly onto adventure at the expense of anything critical of the establishments of his day. This enabled the English-speaking world to assign Verne the status of a children’s writer, and thus more easily dismiss him, while in the Francophone world Verne was a respected literary giant taken seriously by all ages. This smacks of a very British kind of sour grapes, and that deserved to be explored in detail.

Drama proceeded from the very outrage of the notion that a best-seller could be eviscerated, turned into something quite different as it crossed the language barrier, to serve the political and social interests of another part of the world, while cashing in royally on its established success. Before reading Miller’s work I had no idea there was such a story behind the novel but when 20,000 Leagues Remembered came along it presented itself to me four-square and clamored to be written.

P.S.: Another Verne-related story of yours, “The Highest Loyalty,” is in Extraordinary Visions: Stories Inspired by Jules Verne. Tell us how that story delves into the motivations of Captain Nemo.

M.A.: “The Highest Loyalty” was a most interesting exercise as it explored a diversion from Nemo’s scientific cruising for reasons very much to do with the outside world. Verne tells us he supported those who fought to make a difference against corrupt establishments, and it struck me that a submarine would have made the perfect “underground railroad” for snatching souls from jeopardy during the American Civil War.

Given the chronology of events—that Nemo, Prince Dakkar of Bundelkund, was set upon his life’s course by the events of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, and that he escaped with his followers to build the Nautilus in the years after, it follows that Nemo was free and at liberty beneath the sea during the war. Given his conflict with the Western colonial powers, and his commitment to taking no sides, it seems clear he would be a wholehearted supporter of the Abolitionist cause. If this was the case, the Nautilus probably carried many a party of escapees from the South to safety in Union territory, and I revisit this situation at a later date as Nemo comes to the rescue of an Abolitionist agent in jeopardy from the spate of reprisals following the conflict.

Nemo is a fabulously complex character, a man of admirable qualities yet who stands apart from civilization as we know it and will wage war if need be. This makes him eternally attractive to explore, and pastiches provide the opportunity to do so, remaining within Verne’s own timeline (troubled is it is with the Mysterious Island contradictions). Here I had the opportunity to demonstrate the strength of his convictions, that he would place his life on the line to serve a fellow freedom fighter. I have always believed that Nemo was more hero than villain, and exploring this in new prose is a delight.

I have other tales of Nemo and the Nautilus on paper and many more I would like to pursue, so am watching with keen interest for appropriate future calls for submission as might eventuate!

P.S.: What are your current works in progress? Would you mind telling us a little about them?

M.A.: I have a number of projects in hand at this point, each with an eye on a wider marketplace. Hiraeth Books have commissioned two, possibly three anthologies from me. One is a collection of my vampire short stories, the saga of changeling Lucinda Crane, a vampire whose allegiances still lie with the humans among whom she was born and on whose behalf she battles all manner of supernatural foes. I’ve written eight stories to date, the first of which appeared in an anthology from Spectral Visions Press (University of Sunderland) way back in 2014, one of those pioneering pieces that got me started on this course. Hiraeth have picked up others, as did Bards & Sages, for various volumes, and are collecting them all under one cover. This calls for a fresh polish of the whole saga.

Also forthcoming from Hiraeth will be one or possibly two fantasy volumes. “A Triptych of Swords” is my working title, being novella-length pieces in the historical fantasy vein, though with a venture into a full fantasy world as well. I have one piece left to finish for this one, and we’ll see how the project shakes down in the next year or so.

Also on the table is an urban fantasy novel, Venatrix, which mixes a climate-ravaged near future with an enclave of witches who fight catastrophe with chaos magic. Set in Venice and many other Italian beauty spots such as Tuscany, Genoa and Verona, it combines hard-hitting action with modern neopaganism in a blend which I’m hoping will be fresh and engaging. I have a few chapters to go, then will be looking for a small press to take it on.

Also on the horizon for this year will be to assemble that Sherlock Holmes anthology from my previously published material, which will be a most vicarious pleasure!

And lastly, I’m working on the textual material for a dedicated author website, which will feature essays, chronologies and purchase links for all my areas of creative work, with Sherlock Holmes and “Tales of the Middle Stars” in a fairly advanced state of writing.

Poseidon’s Scribe: What advice can you offer aspiring writers?

Mike Adamson: The best advice I can offer to a writer hoping to break into the modern short story market, let alone novels, besides the persistence discussed above, is patience. Understandably, every writer hopes that things will gel in a year or two and he or she will start making some useful income from pro market: that a dozen placements, or two dozen, at the low end will bring you to the attention of the top. This might be the case if the writer is well-connected, schmoozes the book fairs, left university with a first class arts degree in writing, is a graduate of Clarion West or another recognized academy, but for most of us the reality will be a long, slow burn.

Assuming that the writer has wrestled down the particulars of the craft—can use the language effectively, distinguish between forms and styles and know which is appropriate for what market, has the services of a good beta reader or editor to provide a mirror to the writer’s own point of view—then patience is the best tool in the kit, along with self-confidence. Rejection is part of the landscape and learning to not take it personally is a major hurdle. Comparatively few rejections are a measure of the worth of the material: many are based on length or how closely your piece matches a theme, or even—and this is a bitter pill—how well a story a magazine is happy to take “fits” with all the other stories they would like to include in a particular issue. Or they might have accepted something similar recently, or it’s on a theme they’ve visited frequently before…

Taking all figures collectively, since the beginning of 2016 I’ve received over 2700 rejections, most of them of the form type. At all costs, one cannot afford to take it as rejection of oneself. The golden truth is that the very next editor might think differently, so rejection becomes acceptance. That’s the vindication of your work in every sense, and it does happen. Yes, the wider marketplace really is this subjective! Editors are human and they are independent of each other, running their own enterprises, each with his own her own literary agenda, which makes for the wide variety of styles and tastes of magazine out there. This also ties in with learning which markets are a match for the kind of thing you produce, and which never will be. Magazines have target audiences who expect a particular kind of material, and many markets may be plugged into particular niches, not genres per se, but orientations and outlooks, specific even to kinds of narratives or levels of surreality, and you need to be well clued-in to join those clubs. That comes under research your markets, of course, which is imperative.

Then there’s read till your cup runneth over. One should not write in a vacuum, one should know what one’s peers are writing, as well as have a good knowledge of the history of one’s field. And I’ve found, the more you pour in, the more likely it is to run out again, through a keyboard as fresh work—your own. This is not thieving ideas or narrative lines: I liken it more to putting fuel in your literary tank to run the engine of inspiration.

Poseidon’s Scribe: Thanks, Mike. I think your answers revved up my engine of inspiration, and those of others as well.

Readers seeking more information about Mike Adamson can visit his website or follow him on Facebook, Amazon, and Goodreads. He’s been interviewed before, and you can read those here and here.