How will you celebrate National Submarine Day? It’s today, by the way. I’ll offer some suggested activity ideas later in this blogpost.

USS Holland

125 years ago today, the U.S. Navy acquired the submarine USS Holland, designated SS-1. Though small, slow, shallow-diving, and lightly armed by today’s norms, that craft steered a course for all U.S. Navy subs to follow in her wake.

The Holiday

Senator Thomas J. Dodd, back in 1969, introduced a bill proposing April 11 as National Submarine Day. No president since has ever signed it, but submariners don’t need anyone’s permission to celebrate. It’s our day because we say it is.

In Memoriam

Pause today to remember those lost aboard submarines. Working, living, and fighting in a steel tube underwater involves risks, and according to this Naval History and Heritage Command website, over 4000 men have died in U.S. submarines from accidents or enemy action. The majority of these occurred during World War II. Most often, when a submarine suffers significant damage, the whole crew dies together.

Submarines in History

You can read elsewhere about the role submarines have played in U.S. naval history, including World War II, the development of nuclear power and nuclear missiles, North Pole visits, and the first voyage around the world submerged.

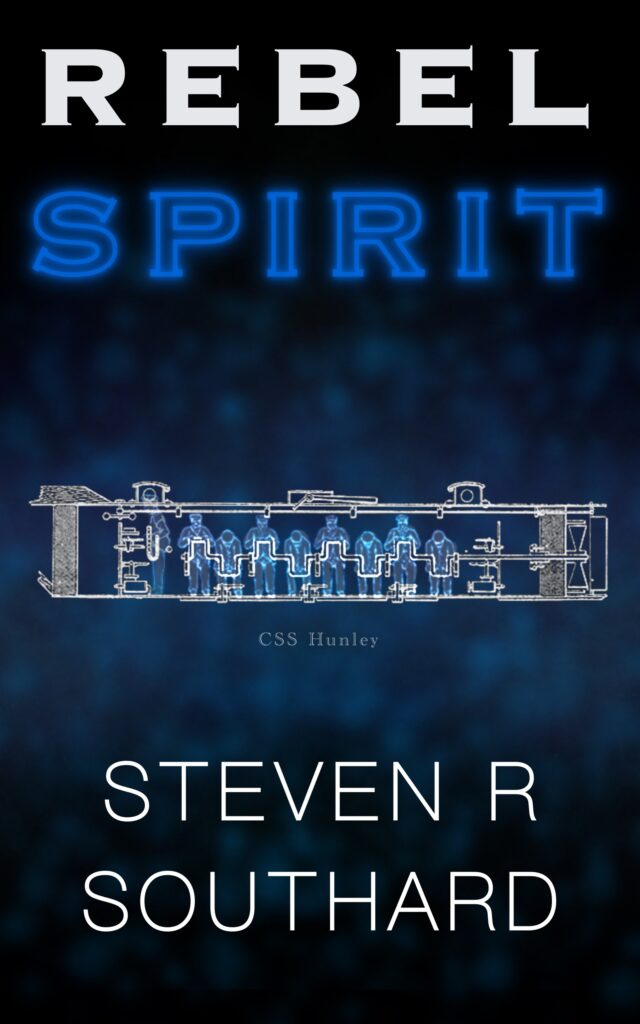

Submarines in Fiction

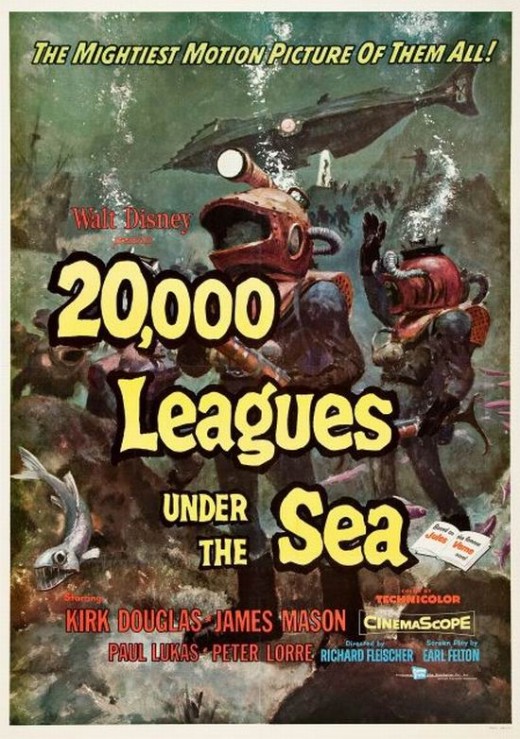

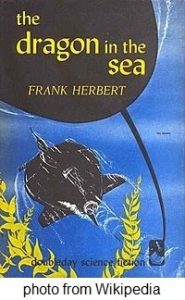

As a fiction author and former dolphin-wearer, I love good stories involving submarines. The best include 20,000 Leagues Under the Seas by Jules Verne, The Hunt for Red October by Tom Clancy, Run Silent, Run Deep by Edward L. Beach, Under Pressure (The Dragon in the Sea) by Frank Herbert, and The Deep Range by Arthur C. Clarke. I also recommend Aquarius Mission by Martin Caidin, The Voyage of the Space Bubble series by John Ringo (especially the last three novels), and any novel by Michael DiMercurio.

My Service

I reported aboard USS Bluefish (SSN-675) in February 1982. Home-based in Norfolk, Virginia, that sub carried me to the Caribbean, Germany, north of the Arctic Circle, and elsewhere during the course of several years. Though I last strode her decks forty years ago, the memories of old Blue remain vivid. So distinct are my recollections that I rendered them in poetry. As a caution to younger readers, “The Good Ship Bluefish” gets bawdy in spots. Read it at your own risk.

Ways You Can Celebrate

Don’t let today pass without doing something to commemorate it. My suggestions follow, but you might think of others.

- Tour a real submarine. Find a submarine museum and take a tour aboard. With the help of your guide, you’ll get a good notion of submarine life.

- Read a submarine story. Consider any of those I recommended above.

- Watch a submarine movie. Options include 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954), Das Boot (1981), The Hunt for Red October (1990), Crimson Tide (1995), Down Periscope (1996), U-571 (2000), Hunter Killer (2018), and others.

- Watch an online video or listen to a podcast about subs.

- Simulate submarine life in your own home

- Assuming you’re eligible, go to your local Navy recruiter and sign up to join the U.S. Navy submarine service.

- If none of the above appeal to you, then just leave a comment wishing a happy National Submarine Day to—

Poseidon’s Scribe

That schedule is subject to change. I’ll post any changes here as I find out about them. There are many other things to see and do at Chessiecon, other than attending my panels, readings, and signings.

That schedule is subject to change. I’ll post any changes here as I find out about them. There are many other things to see and do at Chessiecon, other than attending my panels, readings, and signings.